Drawing A Life at Home

Learning from Ruth Asawa's daily art practice, and her kitchen table

Helloooooo Grown-Ups Table.

Well, today is the last day the GUT will be paywall-free. Starting next the GUT’s drawing assignments, community art share and chat, upcoming 30-day drawing session and live and interactive events will be for member-subscribers only.

If you are not a GUT member and you want to keep getting our art dispatches/lessons/explorations and stay engaged with the GUT community, subscribe today.

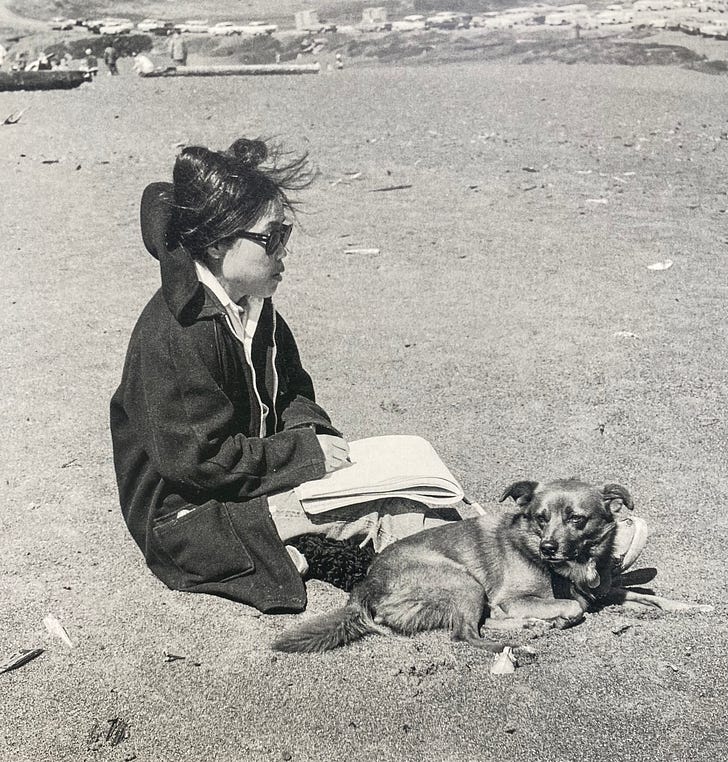

Todays GUT focuses on Japanese American artist Ruth Asawa, whose artistic life grew out of a terrible political and personal experience: her family’s internment during World War 2. It feels appropriate for right now to focus on creativity in a dark time. On looking closely, examining, asking questions and paying close attention. On keeping our imaginations open when we’re faced with fear, anger and outrage - and polarizing positions. Staying creative.

Okay, on with the show.

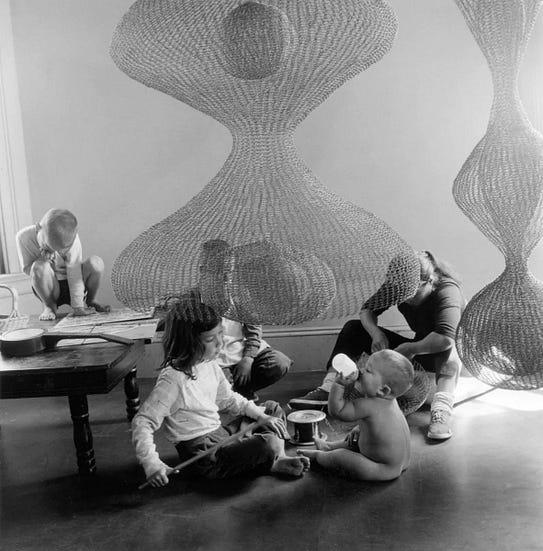

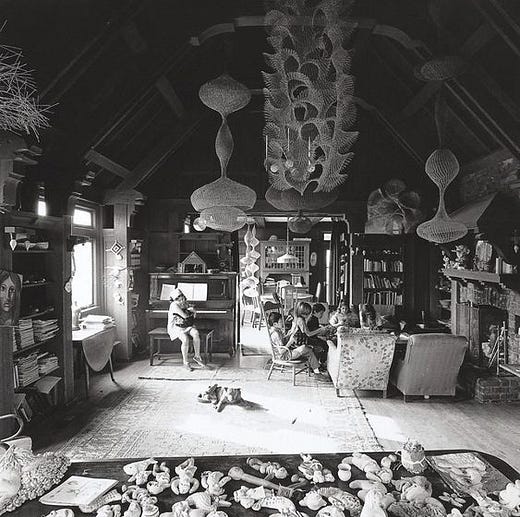

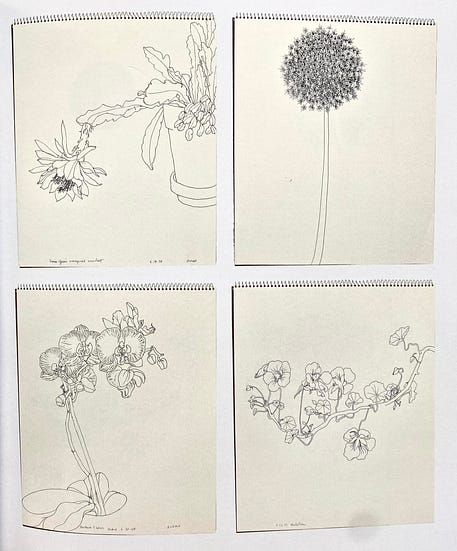

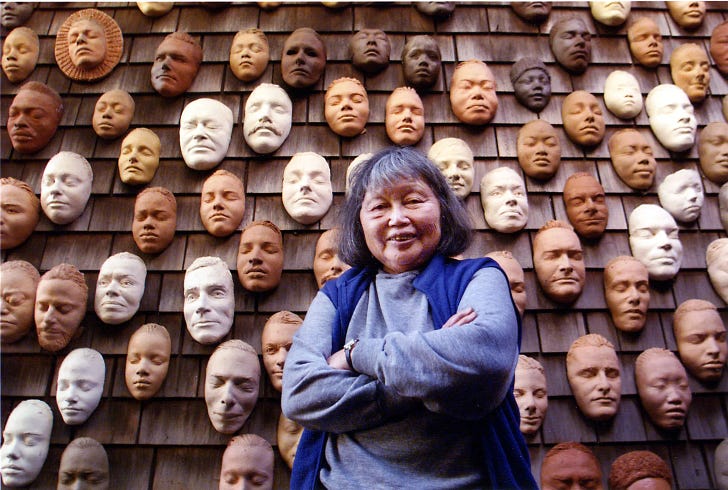

I mentioned last week that I went to the stupendous Ruth Asawa show at the Whitney in NY. While any show of her work will be worth checking out, what makes this show is so special is that it focuses on Ruth’s drawing practice. She is most known for her woven wire sculptures (yes, that’s wha those calming, looping drawings we did a few weeks ago were based on) but she worked across so may mediums: public sculpture, ceramic, ink and watercolor, paper sculptures… she experimented with it all. But all the while there was a through line to her work: her drawing practice.

I’ve talked a bunch about Ruth Asawa here in the GUT - but this week I wanted to learn more about her and her drawing practice in particular. I wanted to understand how drawing captured her attention, what she got out of it, and how she kept her practice going all those years.

So I did a little reading.1 And wow, is it fascinating and there are a ton of interesting lessons to learn from her life that we can apply to our own. So this week I’m sharing a little art history lesson on one of my personal favorite artists, Ruth Asawa, showing you some of her work ,and offering an assignment stemming from one aspect of her drawing practice. If you think you know everything about Ruth, get ready to be surprised. And even more impressed.

Ruth Asawa: Drawer.

Drawing as a Kid.

Ruth started her drawing practice by working on her family’s farm.

How did Ruth Asawa, who drew her whole life, start drawing? It wasn’t in an art studio. Before she picked up a pencil, she picked up a hoe. A rake. A shovel. She picked citrus and vegetables. Ruth started her drawing practice by working on her family’s farm. She was one of seven kids, and started working in the garden early on. Though nobody likely thought of it at the time, all that farming gave Ruth the foundation she needed to create a lifelong art practice: acute control over her hands (aka motor skills), the ability to use them skillfully and confidently at the same time, and the essential foundation of MAKING -“forging a generative synergy between freeing the mind and manual work.” Moving hands = free mind.

Those motor skills and mind/body focus lent itself to learning calligraphy when she was young as well. The practice of Japanese Calligraphy taught her brush technique and spacing - paying attention to the negative space as much as the positive. Ruth said, when you’re doing calligraphy “you’re watching was it isn’t doing. You’re taking care of both the negative space and positive space.” The space we leave open is as important as the marks we make. Practicing calligraphy also taught her about the connection between breath and line: Breathe in on the up stroke. Breathe down on the down stroke.

Beyond this, however, her drawing consisted mostly of copying comic characters from reference materials, and it wasn’t until Ruth was 16 that she started drawing from observation.

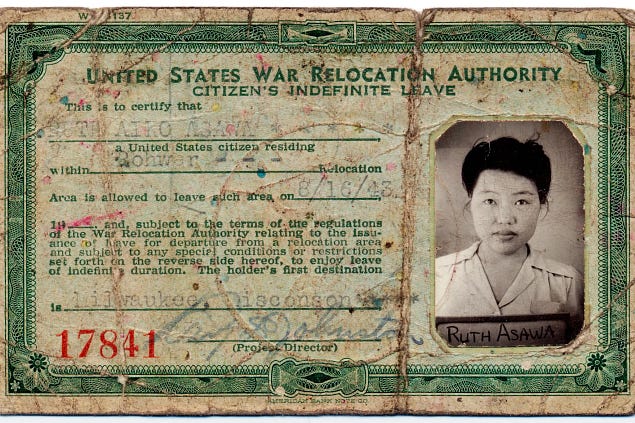

Drawing in Captivity

During World War 2, the United States placed 120,000 Japanese-Americans in prison camps, unjustly incarcerating them based simply on their descent. Ruth and her family were told to park their bags, leave their home, and they were sent to an internment camp for at the racetrack in Santa Anita, California. While it was a terrible experience, there was, for her, a silver lining. It’s where she became serious about drawing.

Some Walt Disney Studio animators were also interned at the same camp as Ruth’s family, and they encouraged Ruth to draw, offering tips and support. With little reference materials, she started using what she found around her as subject for her work. When her family was moved to a camp in Arkansas, she kept drawing. And after she and her family were released, she went onto enroll in drawing classes in college and then wanted to be a teacher. But the USA’s racism had a strong grip on its educational system, and she was told no schools would hire a Japanese American after the war. So instead she enrolled at the infamous Black Mountain College in North Carolina, an epicenter for art at the time.

Drawing as a Student

Ruth credits the instructors at Black Mountain College less for teaching her how to see. Her teachers there included titans of that time who were less interested in the traditional ways of making art, and instead interested in learning how to experience the world - investigate it through making.

Her instructors draw things over and over again - repeat curves and patterns and angles and lines. Pay equal attention to interior and exterior spaces… To “Be Curious” as she wrote in her class notes on day.

One of her most influential instructors, the artist Josef Albers taught her that drawing exercises are never finished. There is always more to explore in everything. He suggested she draw things again and again - repeat curves and angles and lines in different mediums and see what she’d find. The words “Be Curious” were written in the margins of her class notes.

She was there for three years, leaving just twice to travel to Mexico to study, and drew all the time while she was there…. I think it’s safe to say that Black Mountain College is where Ruth got bit by the drawing bug.

It’s also where she met her husband, the architect Albert Lanier.

Drawing at The Kitchen Table

Unable to marry in North Carolina due to miscegenation laws (Ruth was of Japanese decent and Albert was white) they moved to San Francisco and lived in a house in Noe Valley for most of their lives. Between 1950 and 1959, Ruth gave birth to six children. (SIX!) And while that slowed down her art making, she never stopped. Having six kids not only changed her daily life, but it also changed her subject matter.

“I couldn’t go to a drawing class, so I drew my children or the flowers in the garden. I kept my hands in it.” - Ruth Asawa

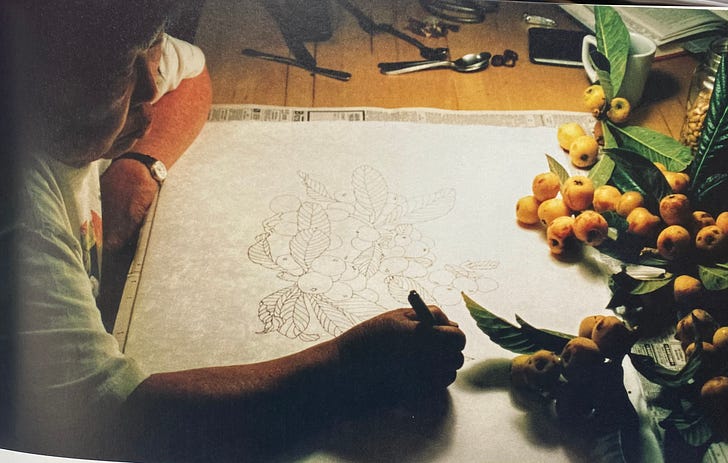

While Ruth passed on the big social parties and such, friends and artists like Buckminster Fuller would pop by the house unexpectedly to say hello. Kids were always running around. And at the same time, Ruth kept a solitary drawing practice that was a regular, consistent, grounding part of her daily life. She would draw while watching television often drawing portraits of the people she saw on TV. She’d draw after the kids went to bed. Her husband would bring home flowers he thought she’d like to draw and leave them on the family’s giant kitchen table, and she’d find quiet (or not so quiet!) moments to sit down and draw the bouquet.

The kitchen table was a the centerpiece of the Asawa-Lanier house.

Ruth’s husband Albert designed and built the huge family table. There were always half-finished projects laying on the surface, materials and subject matter strewn about, and at anytime a member of the family could pause, sit down, pick up a pencil and move their hands. There was always something being created at the table. The kitchen table was about art as much as eating and it was the hearth of their home.

Last year I spoke with Ruth Asawa’s son about how he grew up, and how parents can cultivate creativity in kids through the home environment. Here’s what he said:

In our family house there are tables in every room. A 10’ table in the kitchen, a huge butcher block in the living room. Round table in another room with great light, so you can go there if you need light for a project… It’s good to have a creative place. But it doesn’t have to be a big studio. You need a "spiritual studio." A table that doesn’t matter if it gets wrecked. One that’s scratched already. So if you knick it, it doesn’t matter. Whatever happens to it gives it character.

In 2009, Ruth donated her family’s dining table to San Francisco’s Bethany Center affordable living community. The table, “symbolic of social gathering, community and creativity, formed the start of an arts initiative called Ruth’s Table. Ruth's Table is an arts nonprofit committed to increasing access to creative opportunities for older adults and adults with disabilities.” Her wish as “for the table to serve as a hearth for creativity” for artists old and young.

Ruth passed away in 2013 at the age of 87. She died in her home.

Assignment

This week we are going to channel Ruth Asawa and draw at our kitchen tables.

Everyone has a kitchen table. Maybe you have an actual table in your kitchen. Maybe that table is in your living room, like Ruth’s was. Or maybe your kitchen table is a coffee table in front of your TV. Or maybe it’s your bed! For GUT purposes, we are defining a kitchen table as a place in your home where you sit down and feel comfortable and creative. NOT precious. Where you can make a bit of a mess (maybe with some newspaper laid out.) Where you can concentrate. Whatever that space is to you, that is your kitchen table And that is where we are going to draw this week.

But what exactly are we going to draw??

Chances are there is something in the center of your table. Maybe it’s a centerpiece with flowers (fancy!) Maybe it’s a little sculptural object. Or maybe, like me, it’s a bowl filled with bills waiting to be paid. (Yikes.)

Well, that is what we are going to draw. Whatever your kitchen table centerpiece might be. That’s where we’re putting our attention.

And as we draw, let’s keep top of mind everything that Ruth considered in her drawing practice: positive and negative space, breathing, connecting hand and mind. Investigate the everyday through drawing.

Now, if you want to go get something fresh to draw, that’s great. After all, Albert brought fresh flowers for Ruth to draw. But whatever you draw should be in the middle of your table, and should be something “everyday” that you can examine with fresh eyes and a pen (and maybe some paints.)

I can’t wait to see what you draw, and how doing it at the kitchen table while keeping Ruth in mind impacts how you FEEL while you draw.

Remember: BE CURIOUS. Investigate through making. Hands and mind.

This is a hard time for everyone in the world right now. We are feeling so many feelings, and many of them are confusing and conflicting. One way we can be with them is with our BODIES. Drawing connects our heads and our hearts. It’s there for us in the toughest times. Ruth started her drawing practice as a political prisoner in the United States, and she kept it up her whole life.

I think we can all learn a thing or two from Ruth.

Cannot wait to see your kitchen table drawings. Post them in the chat in the app (I’ll start one tomorrow) and can’t wait to hear how it goes.

Everything is better when we DrawTogether.

xoxo

w

Books and articles referenced in today’s GUT:

Ruth Asawa Through Line, Edited by Kim Conaty and Edouard Kopp, 2023, Yale University Press

Raising Creative Humans, by Me!, 2022, DrawTogether Grown-Ups Table

Inside the home of the late American artist whose wire sculptures have a £4m price tag, Lucy Davies, 2020, The Telegraph

Ruth Asawa, an Artist Who Wove Wire, Dies at 87, by Douglas Martin, New York Times

The Japanese-American Sculptor Who, Despite Persecution, Made Her Mark, by Thessaly La Force, New York Times Magazine

This was a lovely assignment for me. I have a round oak table and that is where I do a lot of home art. I live an apartment of around 600 square feet, so the table is in the living room. I drew on paper I made 5 or six years ago for a work shop I ended up not attending. It is sized ablaca and linen mix. I used walnut ink my friend Barbara and her husband made. A lot of this was about not letting things get too "precious." Am tentative with ink drawings, but drew anyway.

Thank you for the backstory of Ruth and all the links! And those clay masks! 😍 I love the kitchen table sketch assignment.