Sculpting our Stories with Ruth Asawa

A Walking Tour of Art, Advocacy and Engagement

Welcome back! Last week, we spent time with Ruth Asawa’s grandson, Henry Weverka, and got to hear stories about Ruth at home and within her community. And we invited you to share stories about your own communities and the people whose care and support helped you thrive. The chat was filled with beautiful tributes to thoughtful partners, supportive friends, parents who have passed but are with us still, and inspiring mentors. I feel so much gratitude for this community’s openness, trust and creativity. Thank you for inspiring me, and each other. ❤️

We’re going to wrap up our series on Ruth Asawa with… (drum roll, please)

ART FOR EVERYONE!

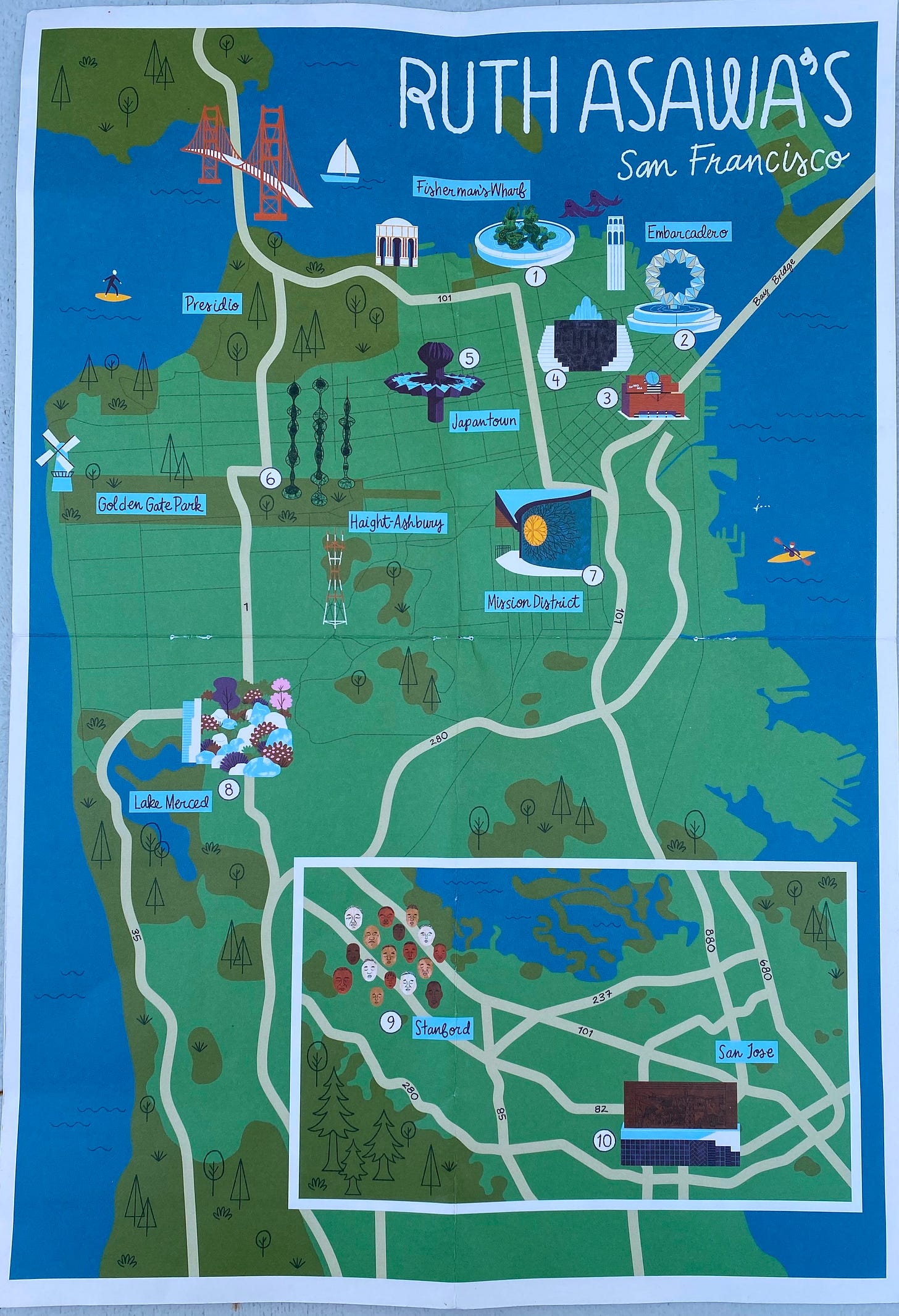

A couple months ago, SFMOMA members magazine came in the mail. Inside, I was delighted to find an illustrated map of Asawa’s public art around the Bay Area. I knew she made public art in San Francisco, but I didn’t quite realize how many places in the Bay you could just stumble across an original Asawa. (And, for that matter, touch it!) Well, you can, and today we are going to learn a little about her public art, where and how she made it, and most important, why.

This is our third and final piece in our series on Ruth Asawa’s retrospective at SFMOMA, and today we’re focusing on her work as a social advocate in her beloved city of San Francisco. For many of us, as we get older, our attachment to place deepens. And after moving into their Noe Valley house in 1961, Asawa really began to put down roots in the city where she lived. She found a place for herself in San Francisco’s social movements of the 1960s. She said, “My investment is in that city.”1 As her investment in her community grew, she thought more deeply about about the legacy she would leave, and stories she thought the world needed to hear and remember. Looking around at the United States today — and much of the world, really — those stories are as relevant and essential as ever.

“This is our legacy, a reminder to all Americans that this can happen again.”

— Edison Uno, a Japanese American who was incarcerated at Manzanar during World War II and wanted more people to know about this injustice. Ruth Asawa included this quote in her last public work in San Francisco.

This week, I am turning over the GUT keys to our wonderful editor Candace Chen, who took it upon herself to visit every single Ruth Asawa sculpture in the Bay Area. (Candace, you rock.) Along with following the SFMOMA’s map, she also listened to the audio tour created by the Ruth Asawa estate with interviews with Asawa’s children and other participants in the work, and is deeeeeeep in the Asawa public landscape. I can’t think of a better person to walk us through Asawa’s public art than Candace, and I’m excited to follow in her footsteps. If you are in the Bay this summer (or ever) I hope you follow in them, too.

Without further ado, Candace, show us the way.

Hi everyone!

I’m so excited to take you on a tour of Ruth Asawa’s public art this week! You won’t be surprised to hear that, just as she drew “Asawa flowers," she also made “Asawa public art”.

If you’re not familiar with the term “public art,” it simply refers to art in a public space. There are many forms it can take — statues, murals, monuments, etc. — but the main thing is that the art is accessible to the public. Anyone and everyone can view it. And with Ruth Asawa, anyone and everyone can make it!

She thought public art shouldn’t just commemorate “important” people like royalty and generals — it should reflect the people in the community. She democratized this art form by working with schools and students and involving fellow artists and supporting their work. I love how she honors her communities in these pieces, while also sharing of herself. I’m going to share about two works I saw that made a deep impact on me.

“A lot of people call her an activist, and she herself called herself an advocate. It wasn't about protests, it was about building something better so that you could, if you need to roll up your sleeves and make the change you want to see. She wasn't going to wait around for somebody else to do it.” — Henry Weverka on his grandmother, Ruth Asawa

A Celebration of San Francisco (in flour, salt, and water)

Since Asawa’s public work began with fountains, we’re going to start with the fountain she dedicated to her city, San Francisco. Its textured and weathered cylindrical shape stands out amid the smooth planes of the modern buildings surrounding it.

As you get closer, you can see amazing, intricate scenes from the city: sunbathers and swimmers, a performance in the opera house, the curves of Lombard Street, and even the wedding of Asawa’s daughter Aiko! But the story behind this fountain is even more incredible and inspiring.

A couple years before starting work on this fountain, Asawa became convinced of the importance of arts education and nurturing young people’s creativity. As her grandson Henry Weverka recalled, “[She] starts the Alvarado School Arts Workshop in 1968 with other neighborhood mothers … with the intent of bringing professional working artists to teach in public schools like she had at Black Mountain College. … Within 10 years it was 50. They had 50 programs at 50 San Francisco public schools.” Working with tight budgets, she incorporated recycled materials and stretched what they had.

She introduced students to baker’s clay, something she had made at home with her own children. Baker’s clay is made from humble pantry ingredients (flour, salt, and water) mixed together and then baked to harden. She realized baker’s clay could be used to sculpt the panels for the new fountain she was working on, and she could include the students’ voices. You can see her working with students on sculpting baker’s clay below:

The creativity and enthusiasm of over 150 students for their city is all over the fountain, but especially in the figures they sculpted of themselves attending Alvarado school. I imagine the pride they felt and the activity of many little hands at work shaping these figures and scenes.

The baker’s clay panels were then cast in bronze by a local foundry, and the fountain maintains the wonderfully tactile nooks and crannies of the clay (maybe there’s even a secret scene hidden within an alcove! Listen to the audio tour!). While museums generally tell you not to touch the artwork, Asawa said she wanted the fountain to be “touched, loved, and patted.” (The SFMOMA actually features another casting of one panel, with directions saying that YOU CAN TOUCH IT! And boy, did I touch it!)

Asawa said, “This experience of bringing ideas together from architects, artists from the foundry, children, parents, and teachers demonstrates how, together, a work is created that neither artist, child, nor adult can produce alone.” Incorporating all these voices resulted in a work that reflects the city’s diversity and vibrant communities. As much time as I spent going through the different scenes, I know I’ll discover something new the next time I visit.

I have to share one more detail that I love. The same year as the unveiling of the fountain, the museum that would become SFMOMA featured Asawa’s first major retrospective, and she held a “dough-in” — “over a thousand parents and children showed up, [and] their creations were baked in the museum cafe’s oven and added to the exhibition.”2 Wish I had been there!

The Courage to Confront the Past

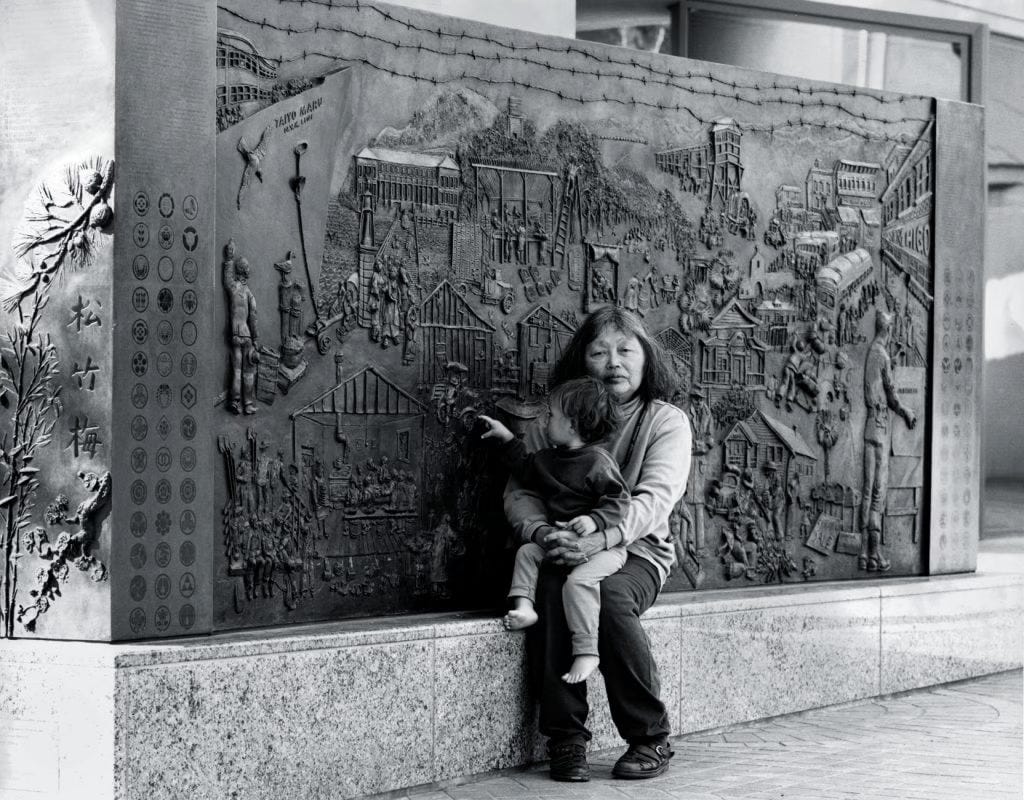

The San Francisco Fountain includes a little of her own life, with that scene of her daughter Aiko’s wedding, but Asawa really gives over the fountain to the city. As she completed her last public works, she was ready to get more personal and to draw on her experiences of incarceration during World War II. With the Japanese American Internment Memorial in San Jose (1990-1994), her public art took on a different emotional and historical weight. The side features the text of Executive Order 9066 which ordered the unjust removal and incarceration of people of Japanese descent on the West Coast in 1942.

In the years leading up to her work on these two pieces, there was renewed attention to the experiences of Japanese and Japanese American people during the war. After decades of activism, Japanese Americans succeeded in getting the US government to hold a Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians where more than 750 survivors shared their stories in 1981. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act which apologized for wartime incarceration and provided survivors with $20,000 in compensation.

Once again, she used baker’s clay to sculpt the scenes of a narrative. Although this time the sculpting was done by her and a smaller team including draftsperson Nancy Thompson and Asawa's children Addie and Paul Lanier, the stories are where she included the voices of the community. She combined painful personal memories such as the arrest of her father with other people’s experiences that she and her daughter gathered from research and oral histories. Starting with the arrival of Japanese immigrants and moving to the mess halls and barracks of the camps where they were incarcerated, the memorial also captured the ways community members supported each other during the injustices they faced.

Flanking these scenes are mon, Japanese family crests. According to a museum placard, Asawa said, “What my family went thru [sic] is the story of almost every Japanese American family.” She wanted all these families to feel their stories were represented and heard.

In the audio tour, Addie Lanier said, “She put in a lot of her biography into this story because it was such a universal story for a lot of the people.” Lanier also noted, “She had never spoken about it to us very much.” This silence was very common among the Japanese American community, which is why the upswell of activism to have their stories recognized was so significant. Many had to overcome feelings of shame despite having done nothing wrong.

That activism was present even during the war. One notable example was Fred Korematsu, who refused to evacuate and was arrested. With legal representation from the American Civil Liberties Union, he appealed all the way to the Supreme Court which upheld the removal orders. Asawa honors Koresmatsu and his quest for justice with this last section of the memorial depicting the government’s apology four decades later:

Speaking on the memorial, Fred Korematsu said, "I have heard people say that they didn't know anything about the internment. Well, here it is... And for those who don't want to talk about it, well, this will talk for them."

Something I deeply admire is how many Japanese Americans have taken their experiences of incarceration as a charge to speak out against further injustices in this nation. They have been some of the most active voices against policies that tear families apart and discriminate against immigrants. Ruth Asawa spoke to this sense of responsibility in her last public work, the Garden of Remembrance at San Francisco State University (2000-2002). She included these powerful words by another advocate for the Japanese American community:

Asawa’s final works of public art call on us to stand together, to draw on our past to better our future. As Henry Weverka said at the end of his conversation with Wendy, “I hope [this show] inspires people to get together and just do something really cool for the next generation. Because I think we really need it right now.”

Let’s celebrate Ruth Asawa the artist, and also Ruth Asawa the advocate. Thank you for taking this tour with me.

Your trusty GUT editor,

Candace