They say you need three things for paintings: the hand, the eye, and the heart. Two won’t do. A good eye and heart is not enough; neither is a good hand and eye.

- David Hockney

Hellllooo fine DrawTogether / Grown-Ups Table artist-friends.

I watched the documentary David Hockney: A Bigger Picture this week. (You can rent it here. It is also available for free via the Public Library/Public University film collection Kanopy.)

A Bigger Picture is a short, intimate, phenomenal documentary that follows the artist David Hockney’s return to his home in East Yorkshire, and his return to the most immediate approach to painting: plein air. This is the first time ever Hockney allowed anyone to film him painting, and he agreed upon the condition that only one person could make it: the filmmaker Bruno Wollheim. No other camera people. No sound people. Just Bruno and a camera and Hockney for three years.

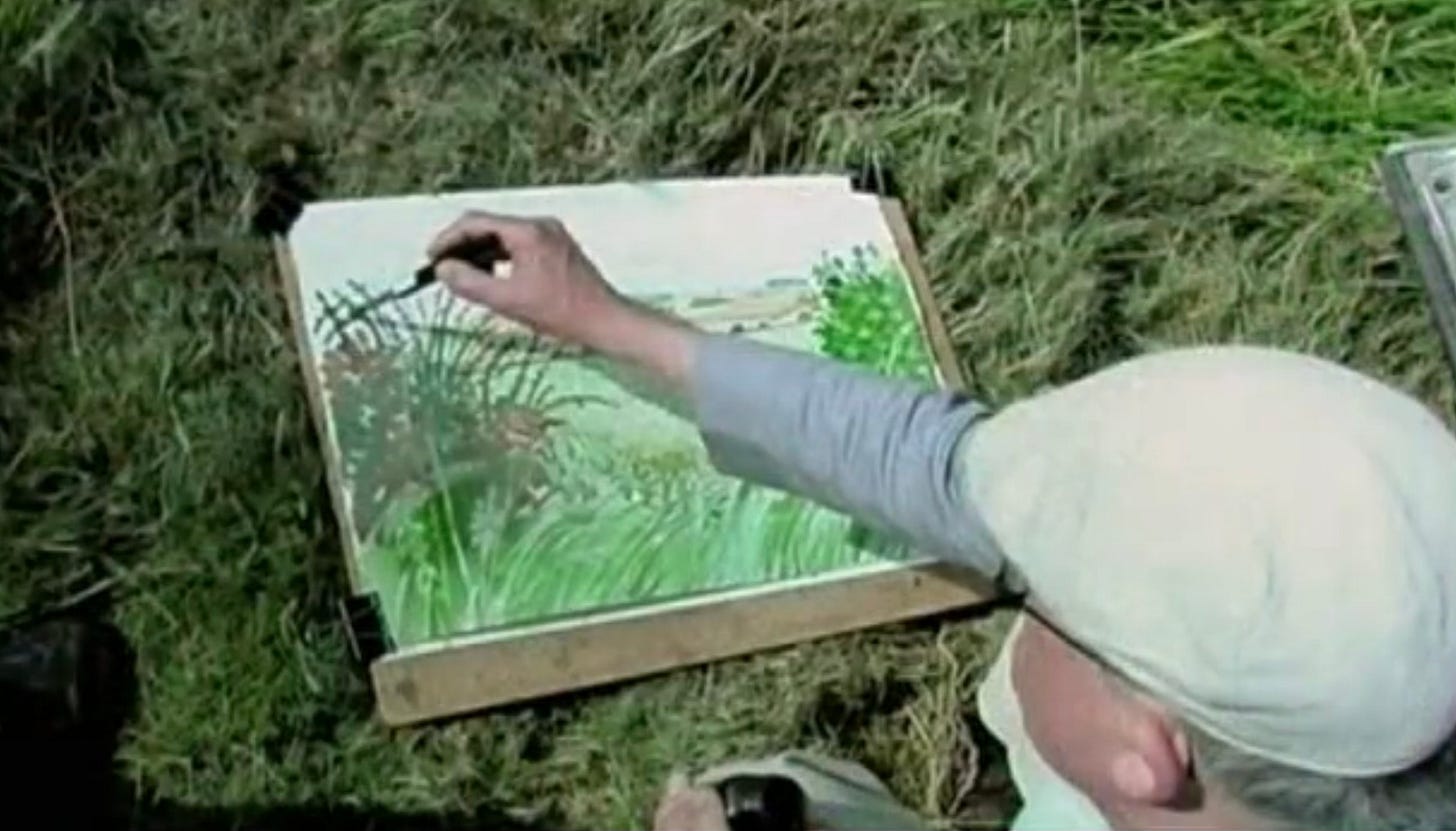

Below is an outtake from the film. In it you can get a sense of how close the filmmaker got to Hockney’s process, and how much we have to learn from the film, and from Hockney:

Including that we should all have an assistant who sets up our art supplies and makes us a picnic lunch.

In just an hour the film offers a revealing peek into how Hockney thinks and paints, and now he thinks by painting. In conversations with the filmmaker, Hockney, now 87 years old, discusses the opportunities and limitations of painting and photography, the experience of making plein air paintings (plein air meaning painting on location), memory1, and why nature is the ultimate, infinite subject.2 More, the film captures Hockney’s wry spirit, clever wit and learned thoughtfulness3. I’m endlessly inspired by Hockney’s curiosity, drive, and experimentation. He sees to continuously challenge assumptions and change his mind- and his work - all while following the thread of making pictures.

You don’t retire doing this. You do it till you fall over. It’s an interesting life. My mind is occupied. That is what you want at my age. But that’’s what I’ve always wanted. I’ve always wanted it.

Related, it dawned on me that while I’ve discussed the benefits of drawing while traveling, we’ve never focused specifically on drawing on location! This week I am going to offer an overview of approaches to plein air, and then do a deep dive on Hockney’s outdoor drawing and painting setups swiped from the documentary.

Then I’m going to turn it over to you. Our assignment this week is a show and tell of our own personal set ups. We’ll share them in the GUT group chat. As basic as a sketchbook and pencil to a pochade box and mobile studio - we all want to see what YOU use to draw on the go. While we can get a lot from experts like Hockney, we also have so much to learn from each other.

So without further ado, let’s get some Plein Air.

Vocabulary

Plein Air: Plein Air is the French for “open air.” In art speak, it’s the practice of artists painting before a landscape or other chosen subject out of doors, rather than in a studio or workshop.

Pocahade Box: The word Pochade is French for “a rough or quickly executed sketch or study.” A Pochade Box is a portable box artists use to make these sketches of studies in nature. It contains an easel, places for paints and brushes and other supplies, and collapsible legs so someone can stand, outdoors and paint.

Field Set or Kit: People use these terms interchangeably, but I’m going to throw down the gauntlet and declare that a field set usually refers to a set of materials like paints or pencils or pastels that are intended to be used in the field. A field kit is the package of all the materials we need when we draw or paint in the field.

Plein Air Drawing Communities

Some people assume plein air = nature. I say no. Plein air can mean drawing on location anywhere, just as long as you’re immersed in the location you’re drawing. There are two general location-inclinations: Nature and City, and drawing communities have formed around each. For the city mouse, there is a group called “urban sketchers” that focuses on people and the life of the city, and for the country mouse, there is “nature journaling” a practice with deep roots in science and illustration.

News: In August, author & nature journaling fan Amy Tan will join the GUT as one of our Summer Visiting Artists!4 Amy will share some of her experience drawing birds in her backyard, give us a nature journaling assignment, and offer us some free giveaways like a signed book and free tickets to the forthcoming Wild Wonder Nature Journaling Conference. (This is for GUT members!)

Note: Some people might try to tell you there is a “correct” way to do “urban sketching” or “nature journaling,” and if you are not following those rules then you are doing it wrong. I could go on a whole rant about what a bunch of BS this is and why they are doing it, but instead I’ll say this:

No. Rules. In. Art.

Okay, onwards.

And! Of course, some folks prefer to draw solo in the field.

Which brings us to one of my heroes, David Hockney.

Hockney’s Field Kit

None of the following is fact checked and all images are blatantly stolen from the documentary David Hockney: A Bigger Picture, so apologies to the filmmaker, but I think it’s worth taking the risk in the hopes that this will encourage you to watch the film and inspire you to get outside and draw yourself.

David Hockney is a helluva painter. he was raised in Yorkshire, England and moved to LA later in life where he lived and worked for 30 years. That’s where his career as a painter really took off, and he was wildly influenced by the town - the people, the light, the color, and the film and photography. For many years, he used photographs as his source material, and at one point he stopped painting entirely and switched entirely to taking photos himself, and then again when we veered to do some deep research on the topic. As he got older and lost the animals he loved, he felt lonely in LA. He and his partner moved back to East Yorkshire to paint and start over. And that meant committing himself entirely to painting directly from life.

“I’m painting landscapes in yorkshire because you can’t photograph them. The camera can’t get the beauty of this. The space. We’ve gotten to a point where we think the camera can phtoographe anything at all. Well it can’t it can’t compete with a painting at all.”

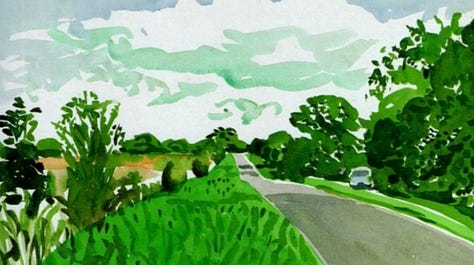

When Hockney arrived in East Yorkshire started by painting in the studio from memory and notes, then decided to move the whole set up into the field to “build up a vocabulary.” His first drawings were pencil sketches and watercolor, and, like Georgia O’Keefe before him, he’d make some of them while sitting in the car.

"I would say STOP! I got a little sketchbook… and i would draw certain kind of grass. I filled the book in about two hours with all different kinds of grass. To most people it looks like a jumble, because it is. But because you’ve done that, if you’ve looked into the hedges and seen all the variety then you draw it, when you draw it and when you look again, you’re seeing becomes clearer and you understand what’s going on more. And you realize there’s a fabulous lot to look at.

While woking on the painting above, it looks like he is using a brush and ink straight out of the bottle, and drawing on paper that is resting on a drawing board.

In the image below, Hockney is working on the same drawing, but he’s moved out of the car and into the grass. It appears he is sitting on the ground and he (or his assistant, maybe) transferred the drawing to a portable board and is using trusty elephant clips to keep the paper flat and in place.

Below is a film still of Hockney working in the field with colored pencils at a folding, portable table. You can see his assistant also brought out the easel. I wonder if that always gets set up, or if hockney was thinking of changing gears. If he works on one piece a day, or movs between several. Also, I adore that he is painting in a suit with a lavender pocket square. Queen, I bow.

As he began painting with oil in the field, his assistant would drive him in a pickup outfitted with a rack system for his wet canvases and his other supplies. Once he got there, I got the impression that Hockney rests and readies himself on a folding chair while his assistant sets up his supplies and gets everything ready.

(Kidding! I do need an assistant, but I would never ask them to set up my paints.)

Below is a still of Hockney’s set up. Let’s take an inventory. What do you see?

easels and sandbags to hold them down

paint palettes in pochade boxes, a ton of brushes in some sort of container

a folding table to hold them all

I know there is also a folding chair for him to sit in, and containers of turpentine and such.

Here’s another one where we can see his supplies a little better. Note the coffee!

And paper towels. We ALWAYS need paper towels.

Of course all of this is way easier with an assistant who will set everything up and clean it all, and a partner who brings you a cheese sandwich in the middle of the day. And also, I am so so happy he has all this support so he can keep doing what he does, which is this:

Looking.

They say you need three things for paintings: the hand, the eye, and the heart. Two won’t do. A good eye and heart is not enough; neither is a good hand and eye.

While Hockney’s set up for his Plein Air painting is probably different from yours and mine, I think we can all learn a lot from him - both about how he works and get ideas on how we might want to experiment with working, too.

Okay, I’m going to feature one more artist and then turn it over to you. This person is way less complicated in her supplies and set up:

Wendy’s Field Kit

Here’s mine: