Drawing with Scissors: Romare Bearden

Family, History, Culture, and Collage with the National Gallery of Art

Hello, my dear DTxGUT friends.

First, I just have to say: Grown-Ups Table Subscriber’s responses to our Christo and Jeanne-Claude inspired drawing assignment were tremendous! From giant kittens rolling all over the map, to a dragon watching over the Rhine, to a public grief swing above the city, to a community of kites flying high, your public art ideas were BIG, audacious and a joy to behold. Subscribers can check out all the drawings in the chat, and add your own.

As we continue our collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, I’m thrilled to take us on a deep dive into the work of a hero of mine, artist (and social worker!) Romare Bearden. This week we’re going to learn about his life, his artwork, and look closely at a collage of his in the National Gallery’s collection titled Tomorrow I May Be Far Away.

Heads up: in today’s assignment we’re putting down our pencils to draw with our scissors. (No running!) Inspired by Romare, we’ll explore the layers of our family, our community, and our history through collage. So, SCISSORS UP.

“My purpose is to paint the life of my people as I know it.” — Romare Bearden

Who was Romare Bearden?

Bearden was a visual artist, activist, writer and all-around creative Renaissance man.

Born September 2, 1911, in Charlotte, North Carolina, Bearden was of Cherokee, Italian, and African descent. He was the only child of college-educated, successful parents. But even for the most successful Black families, life in the Jim Crow South was limiting, oppressive, and violent.

When Bearden was just three years old, his family joined the Great Migration. More than 6 million Black Americans left the South to find a better life and future for themselves and future generations. Bearden’s family moved north, eventually settling in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood. Although he spent parts of his childhood in other states, Bearden called Harlem his primary home until his death in 1988.

In 1920, Harlem was the epicenter of music, art, and culture. And Bearden’s family was in the thick of it. His mother was a local powerhouse: a newspaper columnist and civic and political activist. She and her husband hosted many cultural icons in their home: W. E. B. Du Bois, Duke Ellington, and Langston Hughes were friends and visitors.

His parents were hoping Bearden would become a doctor. But when he was 14, a neighbor gave him impromptu drawing lessons. And like many of us here in DrawTogether, he got hooked.

Bearden studied painting and drawing while attending college in Oxford, Pennsylvania, and Boston, Massachusetts. He transferred to New York University, moving back to the city, where he met Elmer Simms Campbell, the first Black cartoonist for publications like the Saturday Evening Post and the New Yorker. It was a life changing friendship: Bearden began making cartoons and illustrations for various publications, including the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis.

All the while, Bearden kept painting.

After graduating from NYU in 1935, he continued taking classes at the Art Students League of New York. To support himself, he became a (drum roll….) case worker for the city’s department of social services! That’s right: he served the city as a social worker for almost three decades.

A little aside: If you’re familiar with me/my work, you probably know I’m a trained social worker myself, and I believe it is one of the most undervalued educations and occupations around. Romare Bearden doing this work along side his art (or perhaps we could say “in conversation with his art”) just proves: social work for the win. Alright, back to Romare.

Bearden stopped his case work only two years before his solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. (It was only the second solo exhibition the museum had ever had of a Black artist.) He also joined the army, wrote essays and editorial pieces, and created social activist groups around arts and equity—more on Spiral in a second. His dear friends included luminaries like James Baldwin, Duke Ellington, Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, George Grosz, Alvin Ailey, and Jacob Lawrence.

And all the while, he kept making art.

Nina Simone, a musician and a contemporary of Bearden’s, said, “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.” Through both his artwork and his work in the community, Bearden did just that.

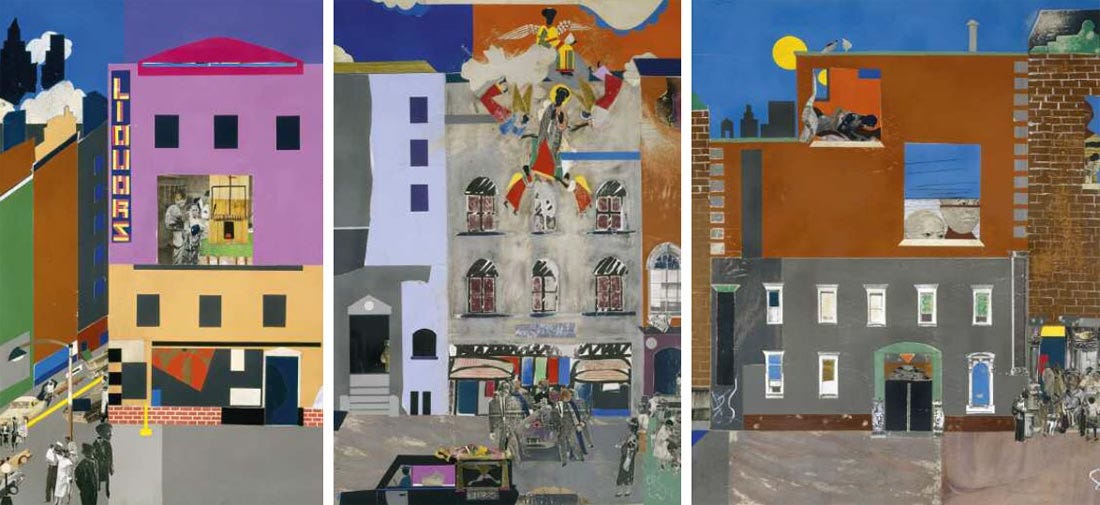

Bearden’s Collages

The word collage comes for the French word “coller,” meaning “to glue.” Collaging is the practice of assembling, arranging and adhering smaller pieces together to create a larger whole.

Fun fact: Bearden didn’t start working with collage until he was 53 years old. Until the mid-60s, he was focused almost exclusively on painting and drawing. That all changed after being part of the artists’s collective “Spiral”, which included such greats as Ernest Crichlow, Norman Lewis, and Richard Mayhew. In 1964, Bearden and other Black artists began gathering in his studio to discuss how they, as artists, could support the civil rights movement. Bearden suggested the group to work on a collaborative piece together, and offered collage as a medium. While Spiral did not take up that project, the conversation sparked Bearden’s interest in experimenting with collage himself.

Bearden went straight to work in his studio and produced a series of small, vibrant collages. Pulling from many different sources and using colorful, patterned papers, he focused these works on the vibrant Black life at the time. Those collages launched the huge body of work he is so well known for today.

Another aside here: What a great reminder that failure only happens when we stop trying. We never know what we are going to make next, as long as we keep creating. Romare’s idea for a group project was rejected, but it opened the door for a lifetime of his own artwork. Challenges = creative opportunities.

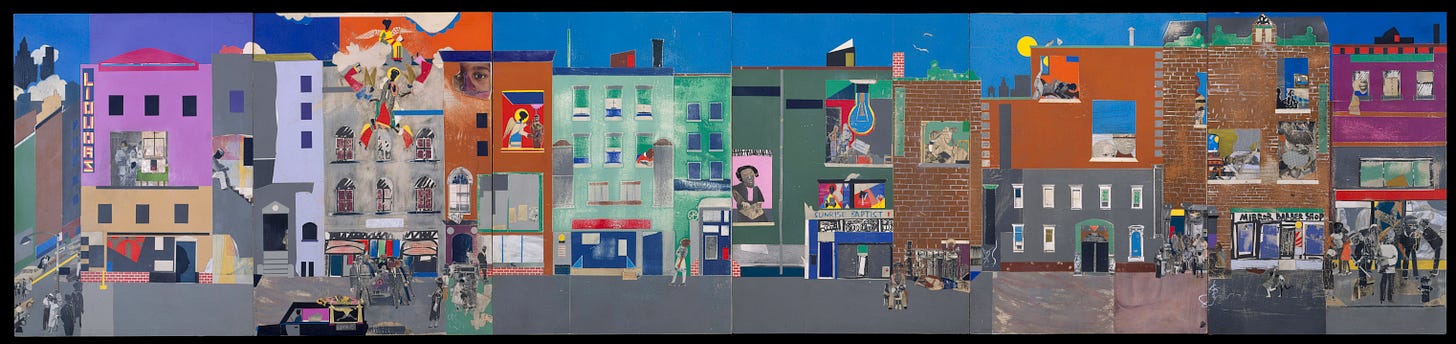

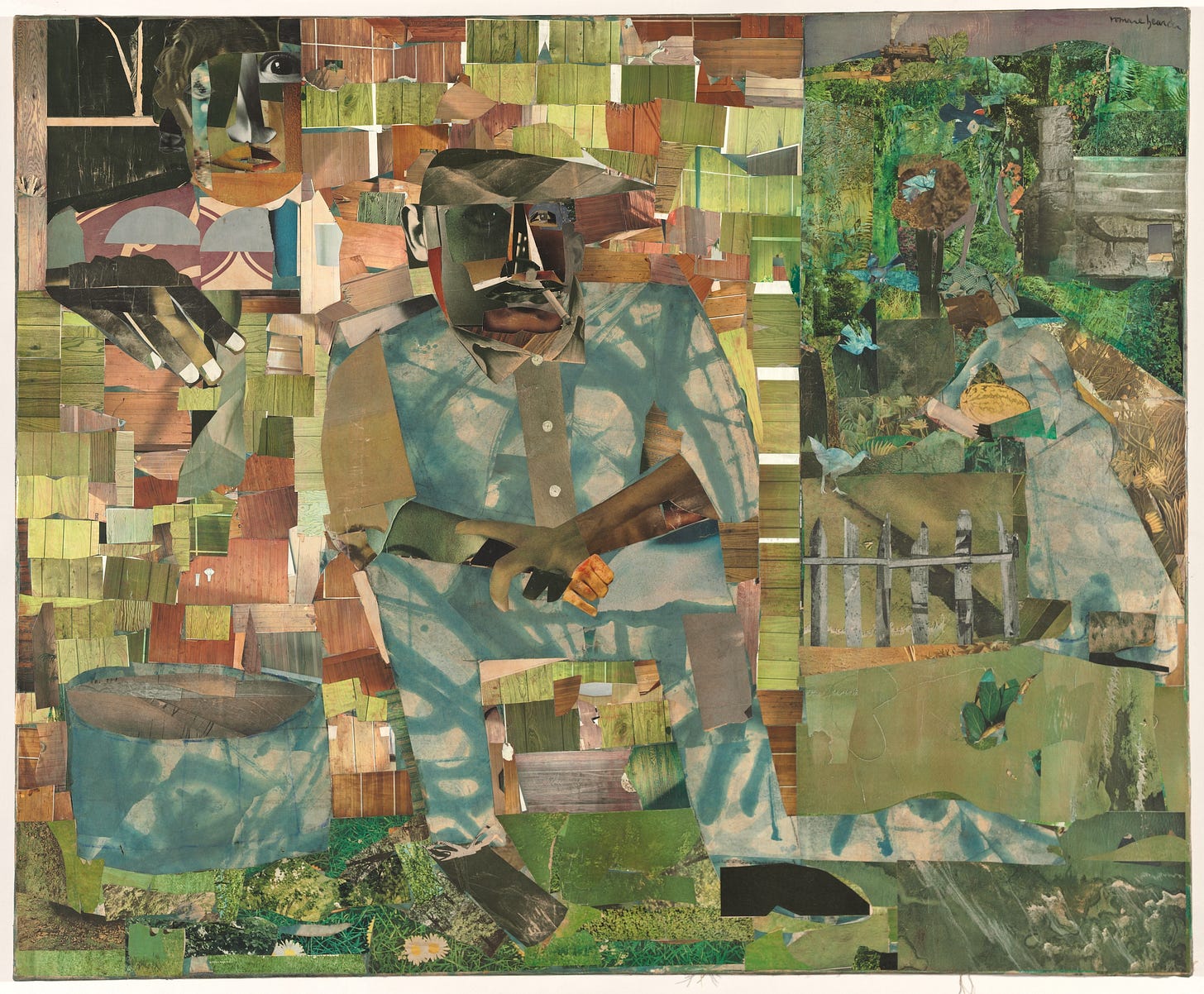

Tomorrow I May Be Far Away

One of Bearden’s most famous collages, Tomorrow I May Be Far Away, is found in the National Gallery’s collection. And it is a giant. Measuring 46 by 56 inches, it’s made with various papers, charcoal, graphite, and paint on paper mounted to canvas. You can get a sense of it in the image above, but when you really have to see it up close to appreciate the intricacy and complexity of the piece. It’s clear how much time and care Bearden took.

Bearden’s influences were deep and wide, often tied to his own memories. He also looked to art history—both European and African—and music like jazz and the blues for inspiration and context. He was influenced by African American culture and history, as well as art and literature.

“When I conjure these memories, they are of the present to me, because after all, the artist is a kind of enchanter in time.” — Romare Bearden

Take a look at the patterned paper all around the main figure in the piece. Bearden used cutouts to create a shingled roof in this work. The shingled house is typical of a building in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, where he was born. Although his parents had moved to Harlem, Bearden would often visit family in the South.

“I put the South in my work because it seems near to me. I can’t seem to exhaust the things I remember.”

I learned that a lot of older scholarship focuses on the woman in the window and the man in the center. We don’t have much information about the other person (on the right), but there are many different readings of this figure. Does she represent a memory and thinking back? Or a hope for the future? Or a fantasy, a daydream? What do you think?

The work’s title “Tomorrow I may be far away” is a lyric from the song “Good Chib Blues,” recorded in 1929 by Edith Johnson. Take a listen below. You can imagine Bearden hearing this music while piecing together this collage in his studio. Using the lyrics as his title makes music a medium in the work. Truly multi-media.

To me, this piece makes me think of memories, textures and fragments of the past we hold close, that make us who we are. It makes me think of family, of community. It makes think of my childhood home.

How about you?

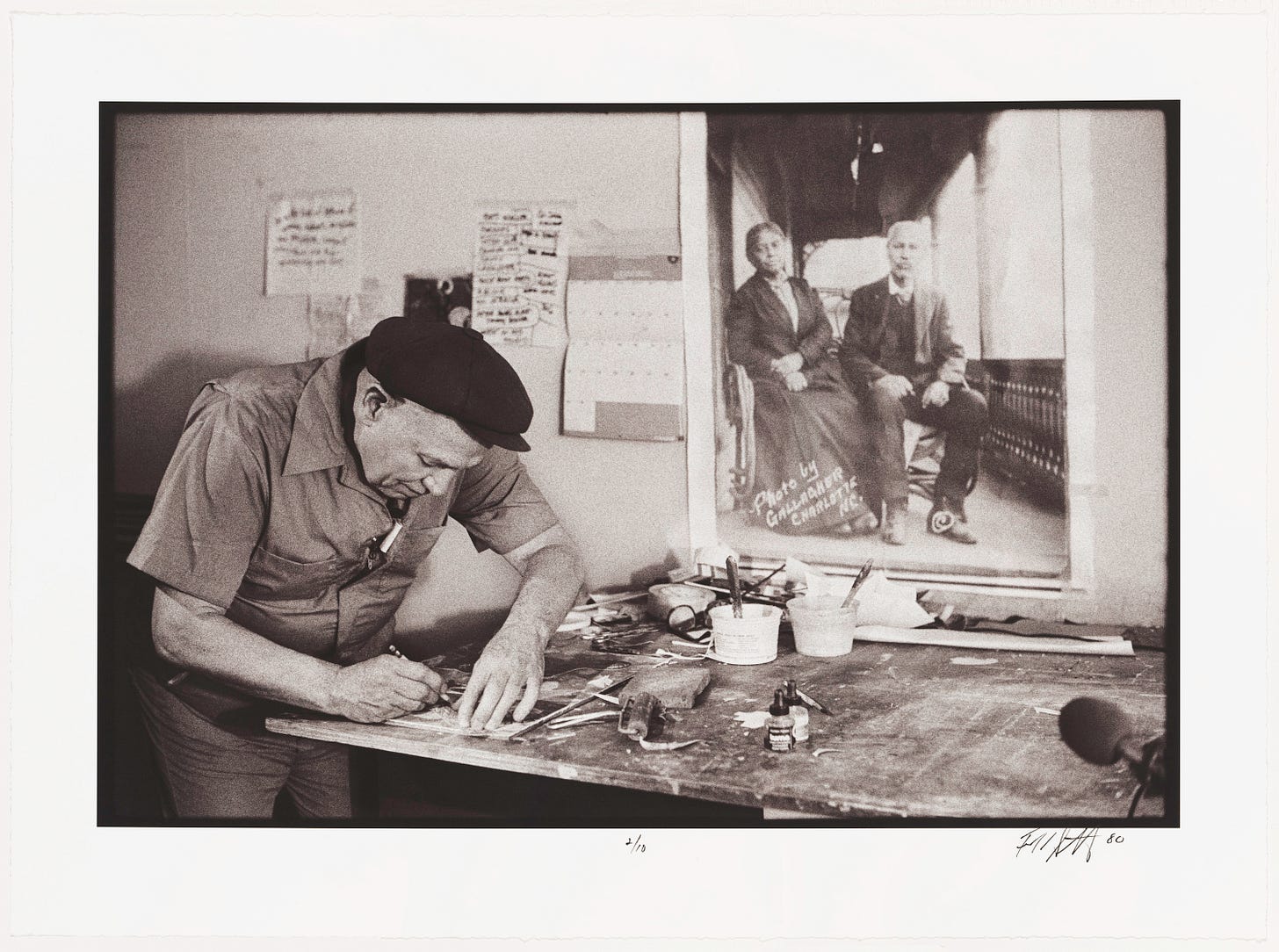

How did Bearden make his collages?

“People have asked me why I use the collage. I find that when some detail such as a hand or an eye is taken out of its original context and placed in a different space and form configuration, it acquires a different quality. In such a process the meaning is extended.” –Romare Bearden

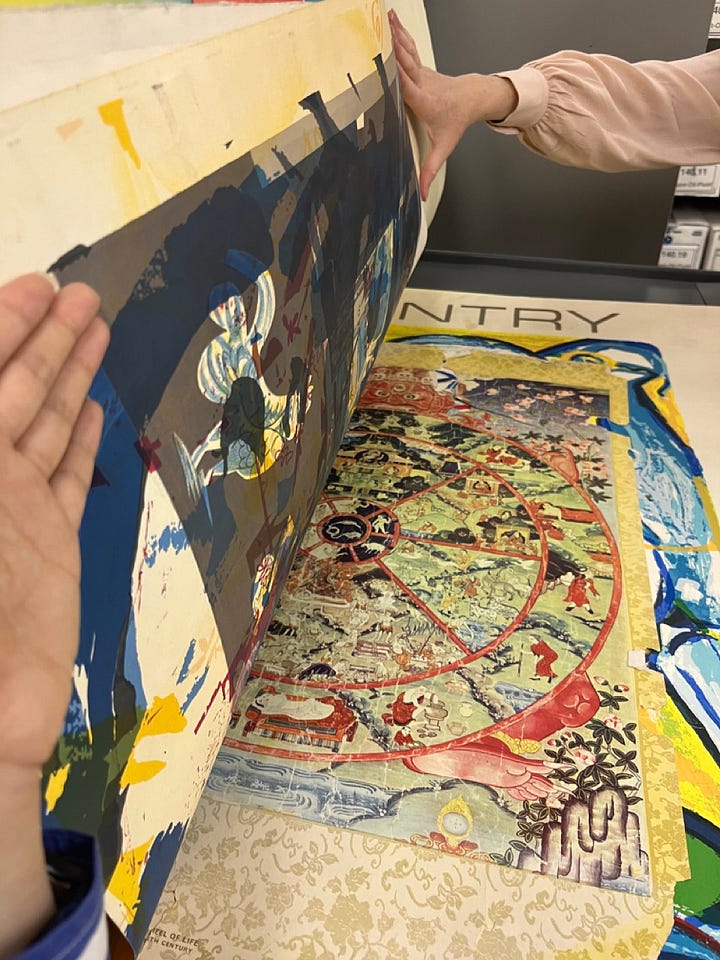

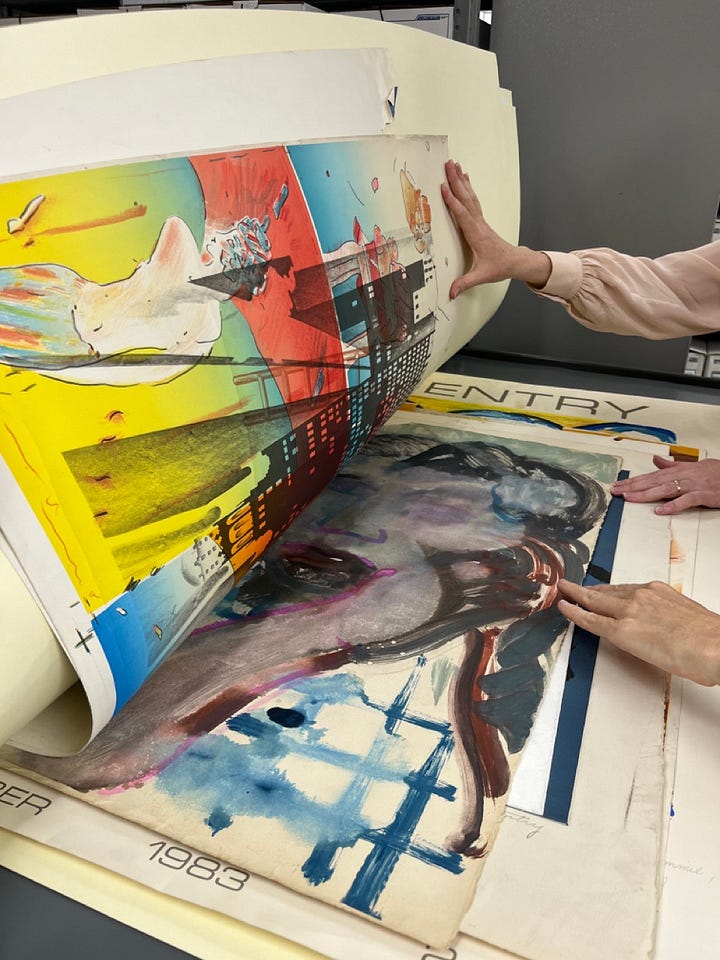

Bearden collected old magazines like Ebony and Jet as well as samples and catalogs from manufacturers. He also painted papers and then cut them for his collages. During my visit to the National Gallery’s conservation department, I got to actually flip through some of his source materials. They included everything from art posters to Chinese restaurant calendars.

Here’s a little about his process, straight From Bearden’s own mouth, that we can learn from - both for the same of knowing how did things, and ideas around composition and color we might want to steal for ourselves.

“I first put down several rectangles of color some of which… Are in the same ratio as… the rectangle I’m working on. Then I might paste a photograph, say, anything just to get my started, maybe a head, at a certain - a few - places in the canvas… I try to move up and across the canvas, always moving up and across…. I constantly find myself adjusting my color to the gray of the photograph so that there won’t be too much disparity in color between them.”1

Not only does this give us insight into his approach to collage but it also offers ideas we might want to consider ourselves.

Bearden passed away in 1988 at the age of 76, in his home of Harlem. He was making art until the day he died.

With that dose of inspiration, let’s pick up our papers, newspapers, magazines, catalogs, wrapping paper, and painted bits and bobs—and draw with our scissors…