Drawing with Our Ancestors: Honoring Indigenous Artists

featuring Wendy Red Star, Jeffrey Gibson, and Dyani White Hawk

Hi friends!

Last week, we wrapped up our series on Overlooked Art Supplies. Our last material: the tiny yet triumphant Post-it! You responded (as usual) with amazing 3x3 work of your own - from animation to bookmaking to mapping - this low-stakes assignment encouraged everyone to take a risk and try a approach. I LOVE to see it it. Members can view and participate in the GUT Gallery - check it out here.

ICYMI, be sure to check out all our overlooked art supply lessons, including the wonders of ballpoint pens, and the underappreciated masking tape. These are great for educators and classrooms, too. Speaking of underappreciation and learning…

It’s Native American Heritage Month here in the United States, and DrawTogether is focusing on Indigenous artists in both the Grown-Ups Table, and over in our educational non-profit, DrawTogether Classrooms. If you are an educator of any sort and would like to bring more art and social emotional learning into your community FOR FREE, join us.

Alright, let’s dive in.

Native American Heritage

While a month is certainly not enough time to do justice to the infinite contributions of Native Americans, it’s a good reminder to pause and look closely at Indigenous narratives, and how often Native Americans’ stories are overlooked or silenced in the US. It’s also important to emphasize that Indigenous people are still here, still a huge part of our country and culture, and are making incredible, powerful art. This is something I want to learn a lot more about. Maybe you do, too. So let’s use this opportunity to explore the work of three contemporary Native artists whose art engages deeply with their heritage while also speaking to our present and future.

Let’s start with the artist Wendy Red Star.

Wendy Red Star, Apsáalooke (Crow)

Multidisciplinary artist Wendy Red Star was an imaginative and curious child. Growing up on the Crow Indian Reservation in Montana, she was always asking questions and loved to draw. But when she went to high school off the reservation, she had that common experience: she was told there is only “right way” to draw. It had to be representational and realistic or it wasn’t art. Wendy promptly stopped drawing and pivoted to graphic design, which she majored in along with Native American Studies.

When Wendy returned to making art, she realized how much she’d already learned years ago from her grandmother who she watched sew and make traditional clothing. As Wendy traced her own heritage and ancestry, she began to make art her own way — less from scratch, and more like a collaboration or conversation with her ancestors.

She first gained renown with work she made in graduate school, Four Seasons. She posed in colorful garments next to inflatable animals and fake backdrops in a cheeky critique of stereotypes and museum dioramas portraying Native people. By placing herself in the image, she called attention to history’s focus on men — warriors and chiefs (that is, if American history features Native people at all) — and demanded a greater focus on women.

I know that my work confronts people with subjects they’re not comfortable thinking or talking about, but if there’s a reprieve in there through humor, it’s so powerful. — Wendy Red Star in Harper’s Bazaar

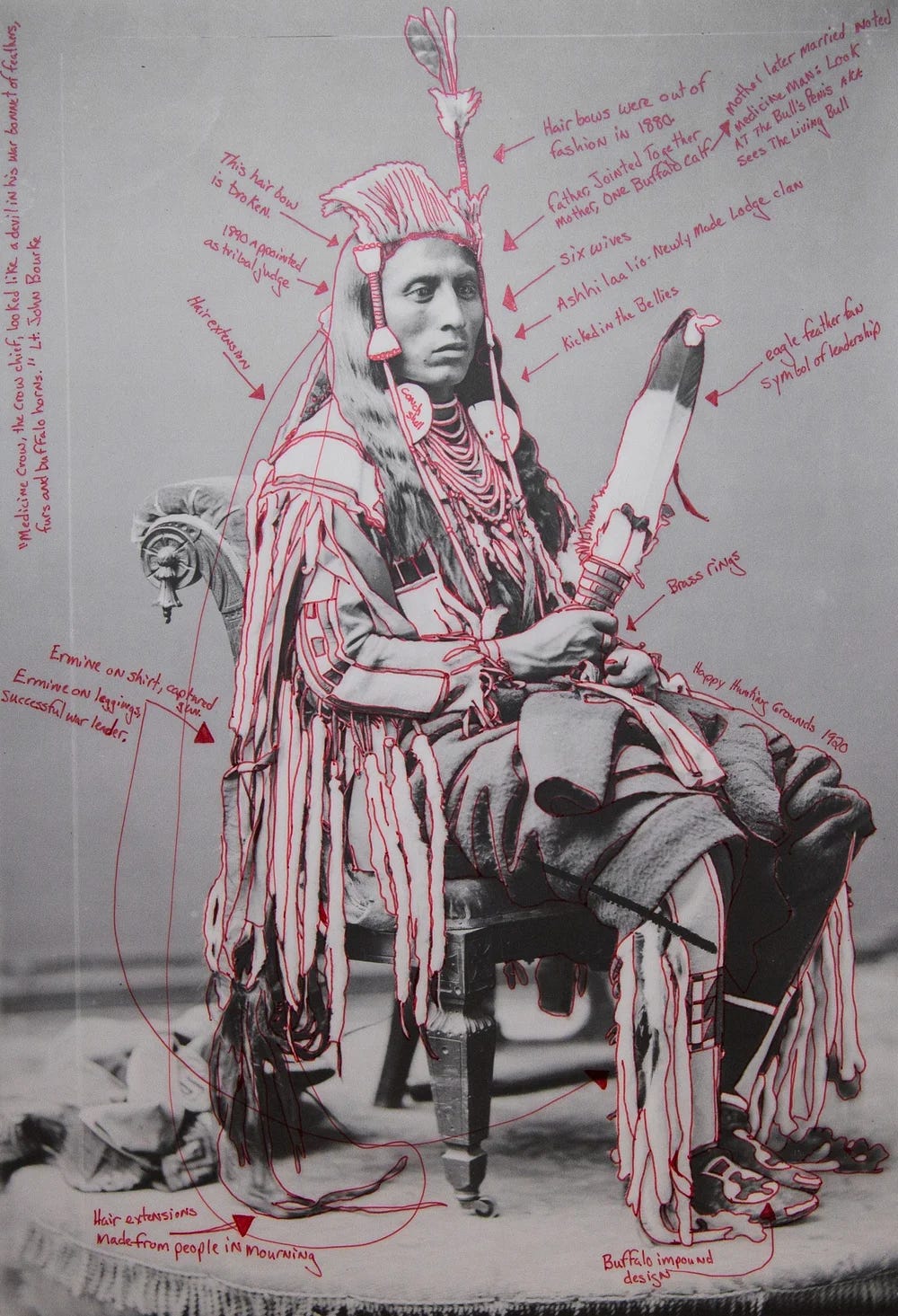

Intrigued by historical photographs of a Crow delegation that traveled to Washington, DC, in 1880, she noticed how the images were shaped by a white gaze — yet still held the beauty of Crow clothing and culture. She began tracing and annotating the photos, reclaiming them by pointing out details and restoring their context.

It is critical to preserve and pass along culture, heritage, and shared values while also providing future generations with a sense of identity, solidarity, and empowerment. - Wendy Red Star at Mass MoCA

Jeffrey Gibson, Mississippi Band of Choctaw and Cherokee

You may remember we looked at the work of Jeffrey Gibson earlier this summer in our Beyond Protest Posters lesson. Since his work deserves a thousand (million!) revisits, let’s take another look.

Jeffrey Gibson draws upon his Indigenous heritage, Queer identity, American and global history, as well as pop culture, to create vibrant paintings, sculptures, and videos. Even as he addresses painful histories of oppression, there is a pride and joy that emanates from his colorful work — an insistence on recognizing the resourcefulness and resilience of Indigenous and other marginalized peoples. In 2024, Jeffrey was the first Indigenous artist to represent the United States with a solo show at the Venice Biennale, and those works were recently on view at the Broad in Los Angeles. In the room above, ancestral figures with beaded text referring to Reconstruction and legislation affecting the civil rights of Black and Indigenous Americans flanked a quotation from Martin Luther King, Jr., advocating for us to see ourselves in relation to history and our own agency.

Throughout his career, Jeffrey has incorporated history into his work. Both of his parents were put into boarding schools where horrific abuses occurred as white reformers sought to strip students’ heritage and culture away. The first step was often cutting their hair. His Biennale show included a series of pieces related to that history: a painting with a quote from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and a series of busts with glorious hair and intricate beadwork. The way the pain in that quotation is met by the joy and defiance of its colors and the nearby busts? Wow.

“We are all the living ends of very, very long threads,” - Jeffrey Gibson, Bomb Magazine

Dyani White Hawk, Sičáŋǧu Lakota

Like Red Hawk and Gibson, Dyani White Hawk is best known for her abstraction. (What is abstraction? That means that the art is not representational but simplifies or abstracts images through color, line and form.) Much of her work is grounded in her Lakota heritage, but she also cites postwar artists like Agnes Martin and Mark Rothko as influences. (Both big abstractors that we’ve talked about a lot in the GUT.) Yet she points out that abstract art is not a recent European invention, and has been present in Indigenous communities for centuries.

Here’s a video on Dyani’s work from the wonderful PBS series Art 21:

White Hawk currently has an exhibition of her work up at the Walker Art Center, in her hometown of Minneapolis. The centerpiece is a sound and video installation titled Listen. She worked with filmmaker Razelle Benally and travelled across America gathering recordings of Native women speaking in their languages. White Hawk points out that even if we aren’t fluent in a language, we can often identify what that language is when it’s Spanish or German… but how many Indigenous languages could you identify by sound? (Such a pointed, humbling question. I remember when I was driving in Arizona and was surprised to come across the Navajo language radio channel. And then shocked at myself — and the US in general — that I’d never heard that before!)

If my work can just incrementally move somebody in a direction where they’re making decisions from compassion, then I’ve done what I can to make my contribution while also fulfilling my own need for creation, which fills my heart and makes me joyful and allows me to be a better human in relationships with the people I share space with. — Dyani White Hawk in Mpls. St. Paul Magazine

Such a powerful quote. Thanks, Dyani.

🚨EXHIBITION ALERT🚨Indigenous Identities

If you are in New Jersey in the coming months, there is a major exhibition of Indigenous art right now at the Zimmerli Art Museum. “Indigenous Identities features 97 living artists that represent over 74 Indigenous nations and communities from across North America and includes painting, works on paper, photography, ceramics, beadwork, weaving, sculpture, installation, and video.” Here’s a great review of the show in the online art publication Hyperallergic. I hope to make it out there. If you do, please share your experience with the GUT crew in the chat.

And with that, let’s learn from these indigenous artists above and explore our own heritage a little.

The Assignment: Honoring our Past

A quick note on Honoring vs. Appropriating

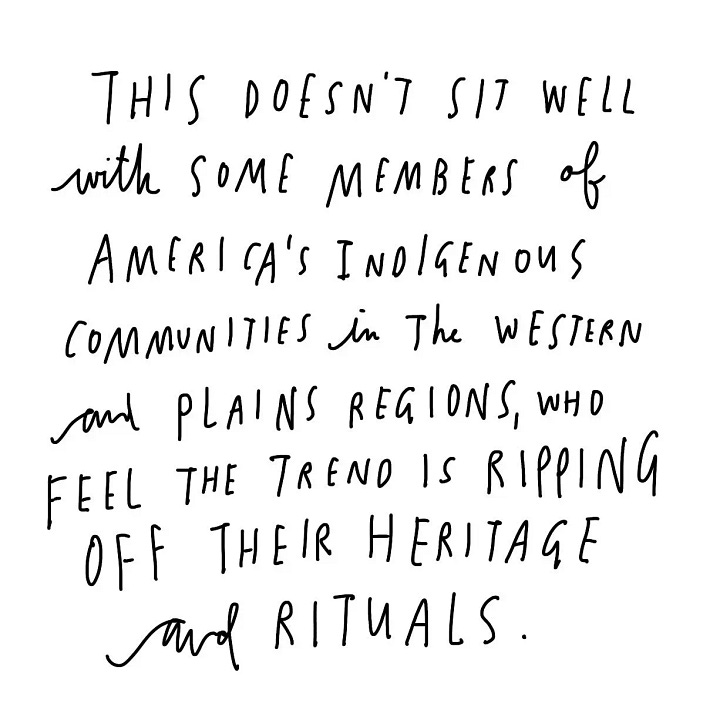

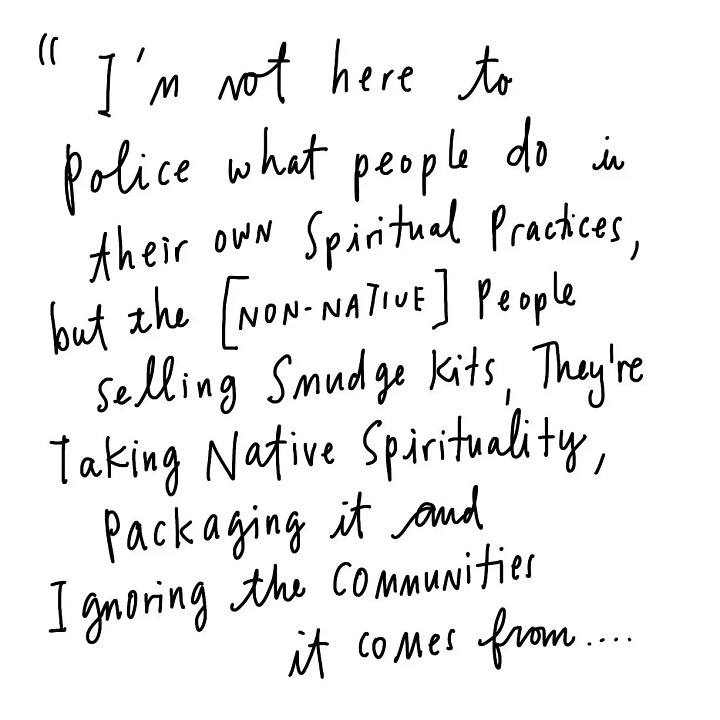

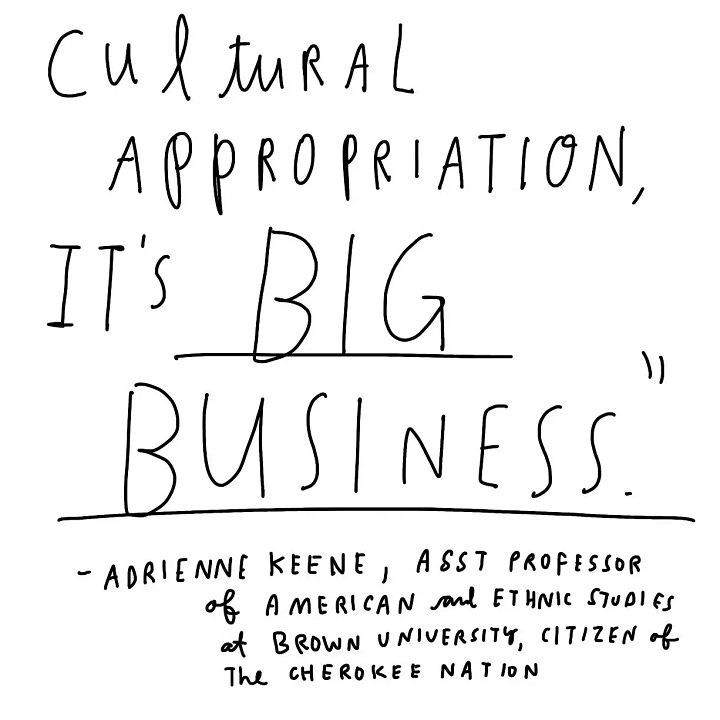

Several years ago, I did a piece for the New York Times about the sharp increase in popularity of white sage as the Native practice of smudging became more widely practiced, especially by white people. I was interested in how Native folks felt about it, so I reached out to Adrienne Keene, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, visual artist, and former professor at Brown University, to ask her take. This was her valuable response:

She went onto suggest that people look into their own cultural lineages and find traditions to pull from there.

As I thought about what we’d draw this week, I asked myself: if we are non-native people, how can we be respectful appreciators and take inspiration from indigenous artists, but not appropriate their approach?

I was taken with Wendy Red Star’s idea of “collaborating with your ancestors” and intergenerational collaboration more broadly: Wendy Red Star has collaborated with her daughter on a number of pieces, and Dyani White Hawk also has generations of her family working with her on beading her pieces. What does it meant to collaborate with our own families, present and past?

Here’s where I landed, and an assignment for you to explore that, too: