Day 3. Connect the Dots

A Picasso-inspired constellation warm up

Hello, my fine Grown-Ups Table artist friends!

My high school English teacher used to say, “Three trees make a row.” If you draw today — day three — for just 10 minutes, then you are scientifically, empirically on a roll. Today’s assignment will officially put you in the direction of a real honest-to-gosh drawing habit. Let’s do this.

I’ve got a real sketchbook-er for you today that you can do anytime, anywhere. It’s a fun drawing meditation, but it’s also kind of a fun puzzle to figure out: a new drawing practice based on the doodles of one of the most brilliant and infuriating drawers ever to have picked up a pen — Pablo Picasso.

Picasso’s Sketchbook

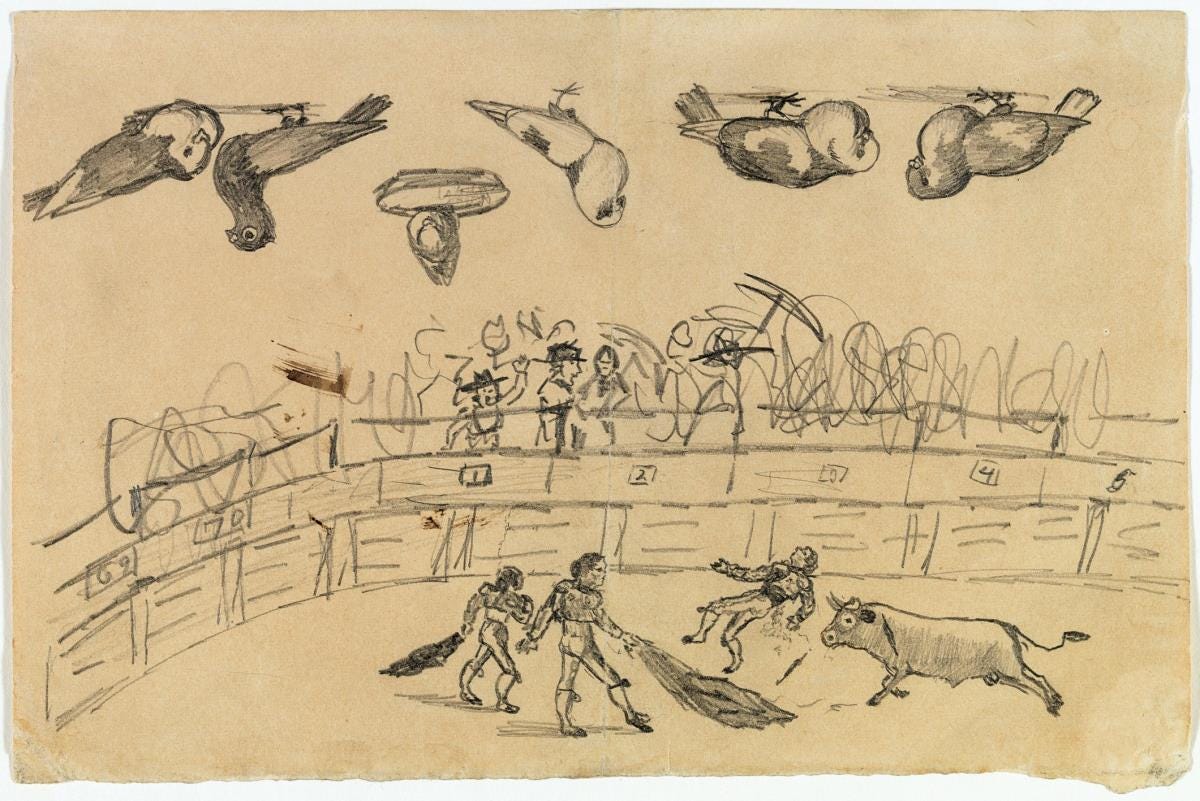

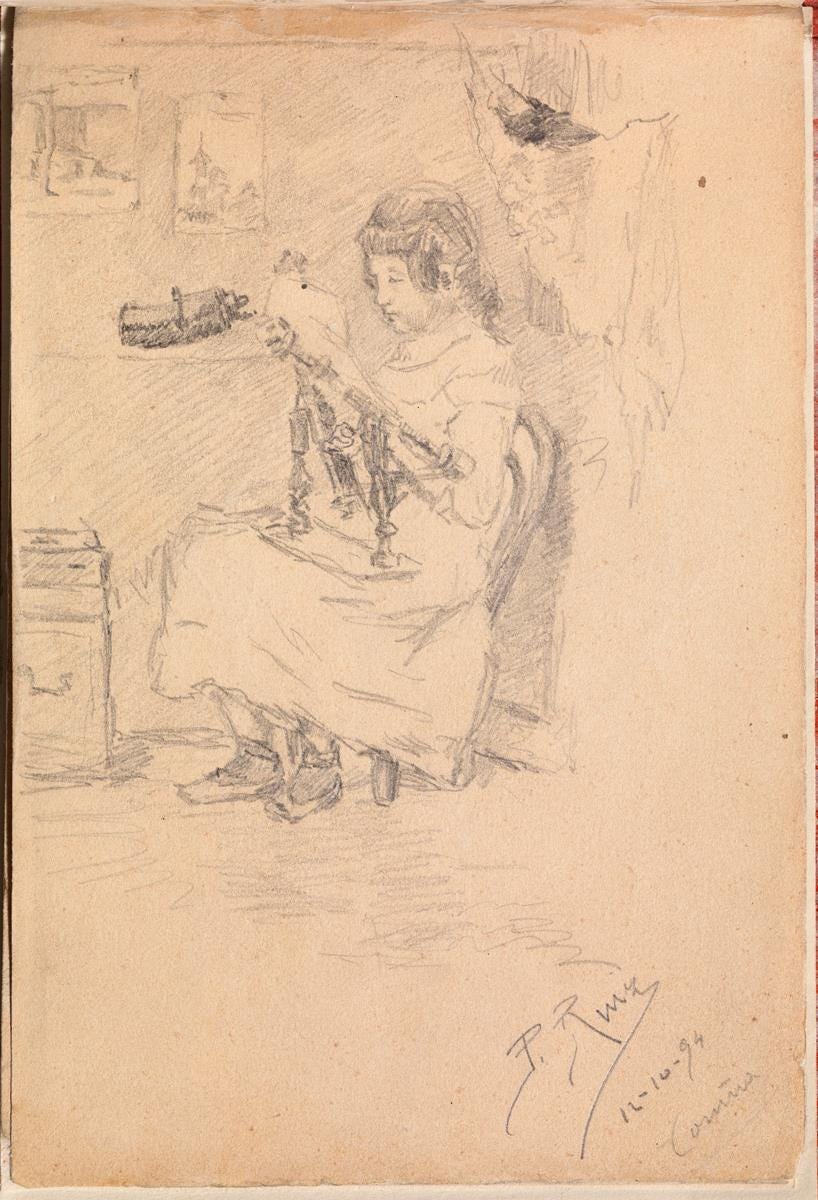

Love or hate what you’ve heard of him as a person1, it’s hard to deny Picasso pushed every creative boundary in his time. Incredibly prolific, he created an estimated 50,000 works in his lifetime. While most know him for his paintings and sculptures, he was also an incredible draughtsman. According to family legend, his first word was “pencil.” His artist father taught him drawing in early childhood and at age 9, he drew this:

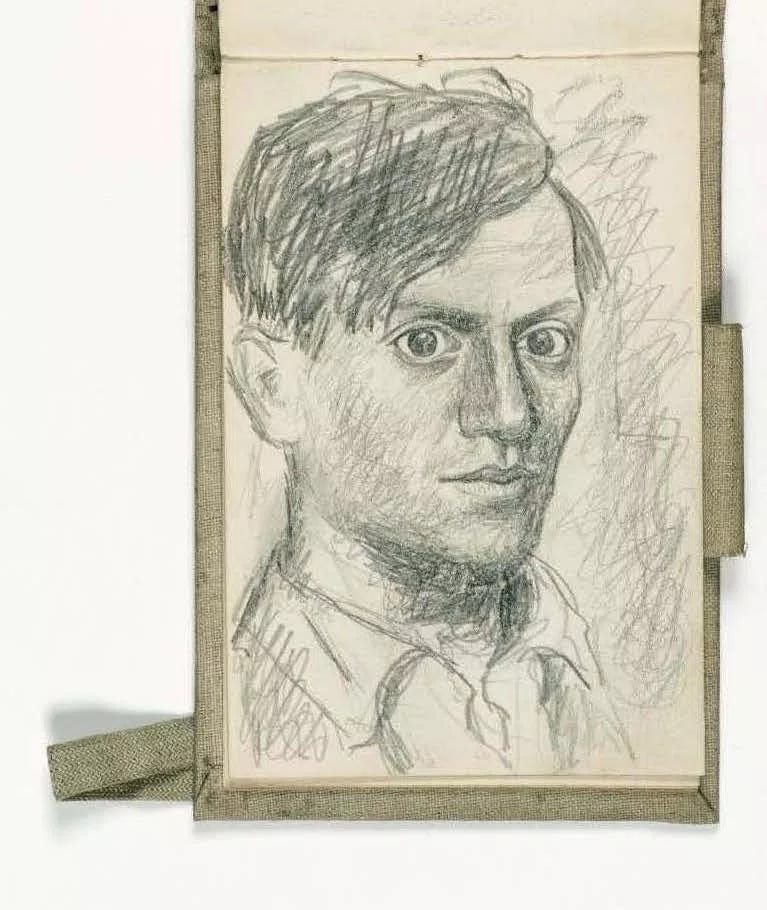

While most of us may be familiar with his classics — his Blue Period, his abstract portraits, his dove drawings, stuff like that — today we’re going to take a peek at something I think a lot of us have not seen: Picasso’s personal sketchbooks.

Between 1894 and 1967, Picasso filled 175 private, personal sketchbooks with drawings.

From the Museu Picasso in Barcelona:

Picasso used sketchbooks as a kind of diary in which he investigated and experimented in order to solve the problems inherent in his creative process. Such was the importance of these sketchbooks for the painter that in 1907 he wrote on the pages of one of them: “Je suis le cahier” (I am the sketchbook). Moreover, he never disposed of most of his sketchbooks, but instead kept them with him all his life.

Picasso gifted the Museu Picasso 19 of these sketchbooks. Those 19 alone contain 1.300 drawings.

Practice Practice Practice

When people ask how I developed my style of drawing, my particular line, I respond by asking them “how did you develop your particular handwriting?"

We develop our lines — handwriting and drawing, both — through thousands of hours of practice. Not effortful, deliberate practice, but simply by doing — again and again and again. When I look at Picasso’s paintings, as distinctive and recognizable as Einstein’s hair, I now understand how he got there: it was through those tens of thousands of drawings he made in those sketchbooks. That’s how you develop such a confident, loose line. Practice practice practice.

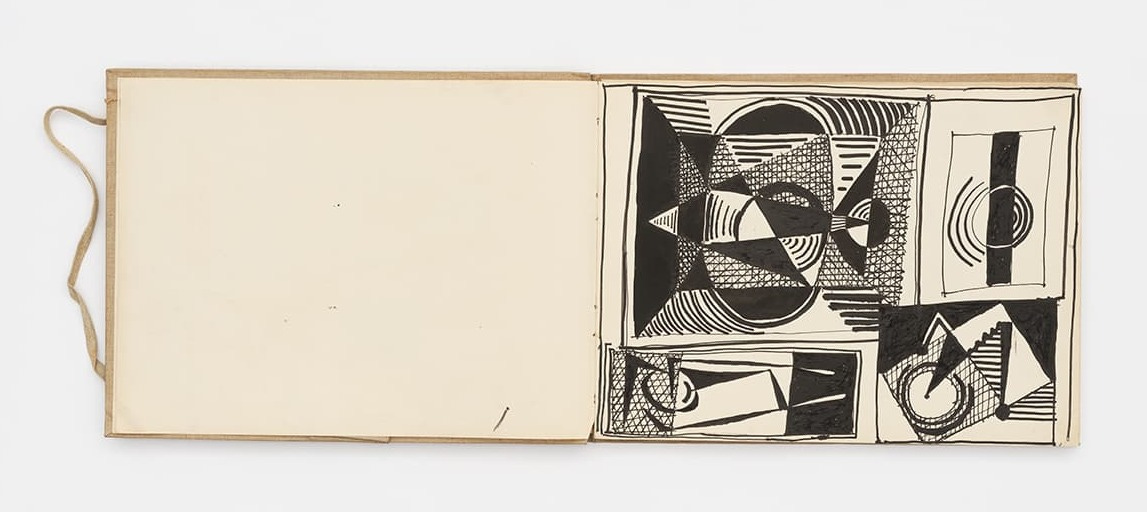

Of all the different types of drawings in his sketchbooks that I have seen, one style stood out to me more than any other. It’s something I’ve never seen him do anywhere else. He called them his “constellations.”

Picasso’s Constellations

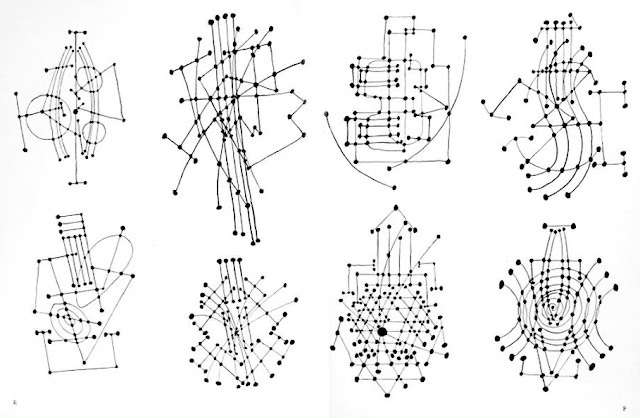

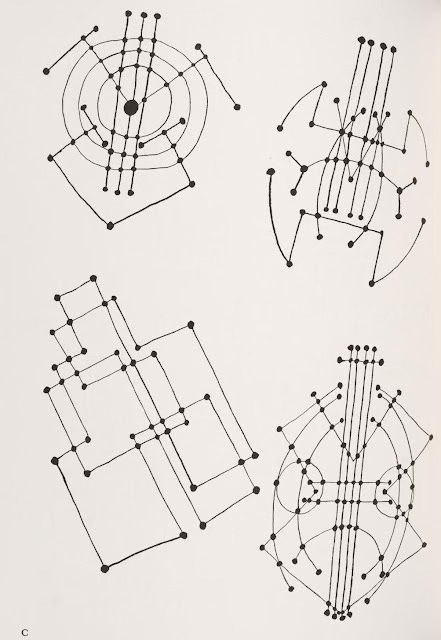

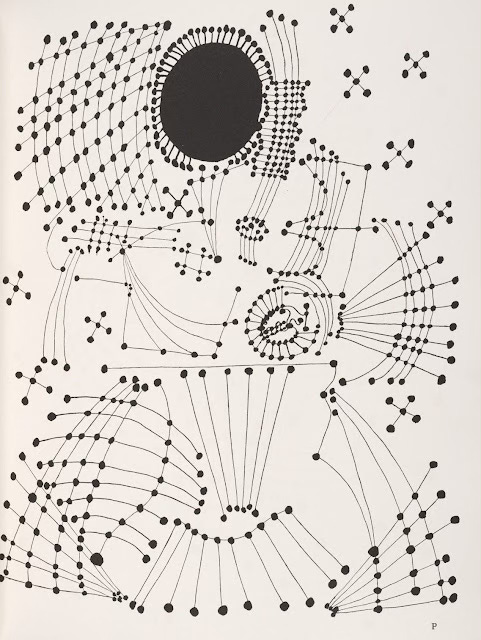

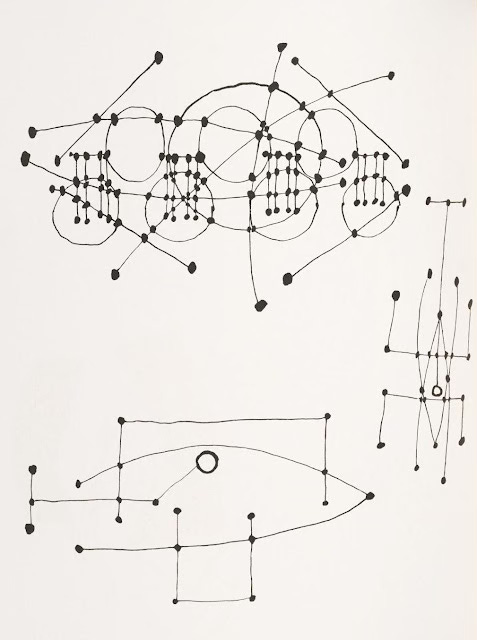

While many of the drawings in Picasso’s sketchbooks are representational — meaning they are meant to resemble a subject that exists in the world, sometimes through observation — some are entirely abstract. You could even call them “doodles.” I love these little drawings. They remind me of complex mobiles, or architectural drawings, both of which rely so much on balance, weight, scale, (a)symmetry… some key considerations in visual art.

I did a little digging into their origin and found this around the web: “According to biographer John Richardson, in the summer of 1924, ‘The splendor of the meridional sky... inspired Picasso to create his own constellations: ink dots connected by fine pen lines that turn the zodiac into guitars and mandolins and the crotchen-dotted staves of musical scores.’”2 These drawings span 16 pages in his 84th sketchbook.

And after a little playing around with drawing them myself, I can understand why Picasso went on such a constellation jag. It is incredibly relaxing to create a constellation. It really syncs up the body and the brain.

And so, for Day 3’s drawing assignment, should you choose to accept it…