Color, Line and Calligraphy

Learning about new artists and art from the West Bank and beyond

Hi, GUT fam!

HELLO. It feels so good to be back into a more regular routine and interacting with you all in the chat again. I love seeing how our community is growing wider and getting deeper. Many of you have been here for years, and others found the GUT through our 30 Days of Drawing, and now continue to keep drawing - on your own or in community - as part of your daily lives. The friendships I see blooming in the chat, the celebration of each other’s brave creative leaps, and all the encouraging welcomes and support you all offer every new member remind me EVERY DAY that we are creating something so special and needed here at the DrawTogether Grown-Ups Table. I am so, so happy you’re here, and that we get to draw together.

I’m not sure how it’s only been a week since DrawTogether Strangers at The National Gallery of Art. Time Flies.

While last week was a life highlight, I am also so darn happy to have that big push past me and be back at home. While I love the excitement of big public projects, I also need the calm of a small private life. Not only do quiet days at home give me time to settle into my thoughts and reconnect with my body (exercise! sleep! imagine!), but it also opens up space to reconnect with what is going on in the world outside myself.

So it’s no surprise that when last week’s dust settled, my heart re-opened to people affected by the war in the Middle East.

WAIT. DON’T STOP READING. THIS IS ABOUT ART & PEOPLE.

I debated long and hard about sharing this dispatch. Honestly, I wrote several much longer versions that I deleted. I’m afraid about even using the words “Israel” or “Palestine” right now. I’m worried that half of you will hit “Unsubscribe,” and we’ll lose our connection. (Please stick with me.) At the same time, this is so important, and a dimension of this war has everything to do with what we do in DrawTogether: People.

I am not a historian of the Middle East. I do not understand the thousands of years of fighting over religion and land that got us here. But I do know something about people. And how when we stop looking at a person as a fellow human - when we stop looking, period - it becomes all too easy to dehumanize them. And this has EVERYTHING to do with the atrocities going on with the Palestinian people and with the Israeli hostages. And it also has everything to do with looking, and drawing, and connecting; all the things we talk about every week here in the GUT.

And so, if you’re still reading, and you’re still with me, thank you for taking a leap and making the connection between the war and what we mean when we say, “Drawing is looking and looking is loving.”

This dispatch is about how important it is to slow down, look closely, and see beyond our biases and expectations. To learn about all different people and ways of seeing and being and experiencing the world. Which is to say, it’s about drawing.

Broadening The Artists and Art We See.

Maybe because it’s what I know best (I’m Jewish), but I have featured the work of many great Jewish artists here in the GUT. Several of them use their art in pursuit of social justice and civil rights: Ben Shahn, Saul Steinberg, and Maira Kalman.

As I was reflecting on where I put my attention and what I share with you here on the GUT, I realized there are also artists I haven’t featured. For example, I have only shared maybe two works of art by Arab artists. And I have never shared any work by any Palestinian artists. And I didn’t even notice.

This, my friends, is called a BLINDSPOT. This is called bias. And it’s the literal opposite of slowing down and looking closely, which is what we work on doing here in the GUT.

Attending art school in the USA in the 90s, I was raised on a diet of Euro-centric, White, cis, male artists’ art. That impacts how I see the world and who is and who is not included in my view of art and art history, and also who and what I do/do not share with you here on the GUT. Those are biases. I have them. You have them. We all have them. Good news: when we see we have them, we can change them.

Looking at art by new artists, especially artists from cultures other than our own, broadens our understanding of what’s possible in art: aesthetically and conceptually and emotionally and intellectually, all the “ally”’s. We get to learn about other cultures and ideas and history and life experiences… we feel new feelings, gain a new sense of wonder…. new human possibilities. We SEE more.

So, in an effort to widen and deepen my view - and our view here in the GUT - I’m recommitting to learning more and sharing work from artists that extend well beyond my own knowledge/culture. And this week, we’ll start by looking closely at the work of a few Palestinian artists. Our assignment, sort of like the post I did about the Jewish artist Ben Shahn (remember this lesson we did on the importance of copying?) is to create a drawing inspired by some of the principles of these artists’ work. Sound good?

Alright then. With that, let’s do this. Let’s slow down, look close, learn, connect, and draw. And let’s do it together.

Artwork of Palestinian Artists

I am going to focus on three artists today, but first I wanted to share an image I saw in the online art publication Hyperallergenic that really struck me. The photo below was taken at the re-opening of the Palestinian Museum in the West Bank just a month ago. It was closed for repair for four months after it was bombed at the start of the war. When they reopened in February, it was with this giant group show of Palestinian artists, some of whom were killed since the war. Over 350 people came together at the museum to celebrate (re)opening night.

Even in the hardest times - especially in the hardest times - people need art, and people need each other.

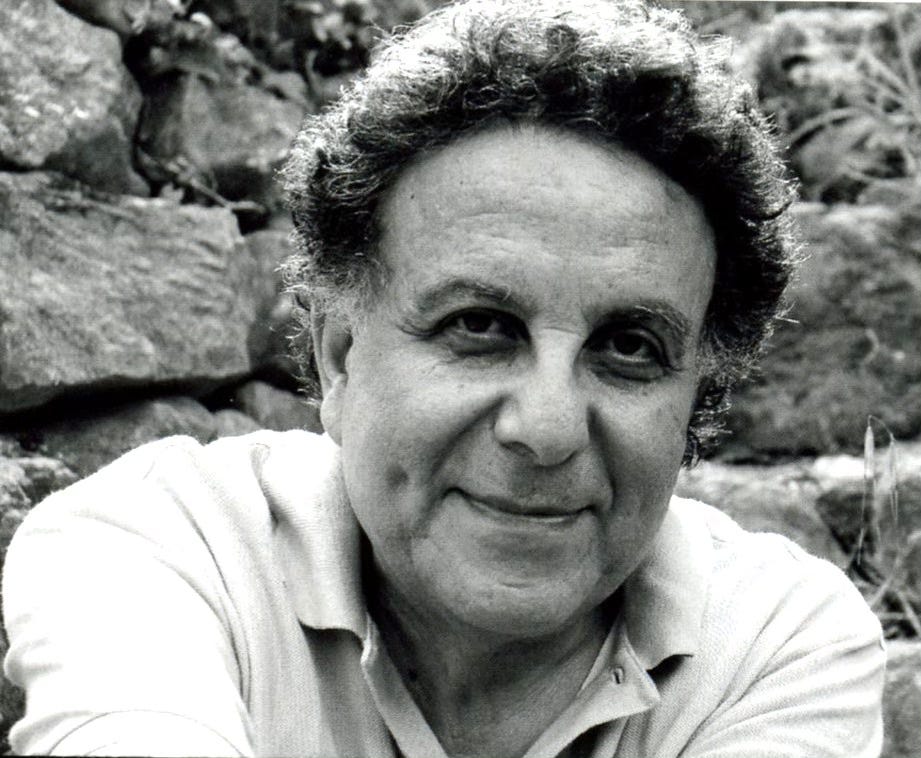

Kamal Boullata

Kamal Boullata was a Palestinian artist, writer and art historian. (He passed in 2019.) He worked mainly in acrylic, with a keen focus on silkscreen printing on paper. Born in 1942 in Palestine, he often told stories about spending much of his childhood drawing the detailed designs contained in the Dome of the Rock, the the oldest Islamic shrine, built in Jerusalem the late 7th century. Those intricate designs show up in his often complex artwork that incorporates abstract design and Kufic script, an angular, flat, horizontal style of Arabic script, symmetry and asymmetry, past and present.

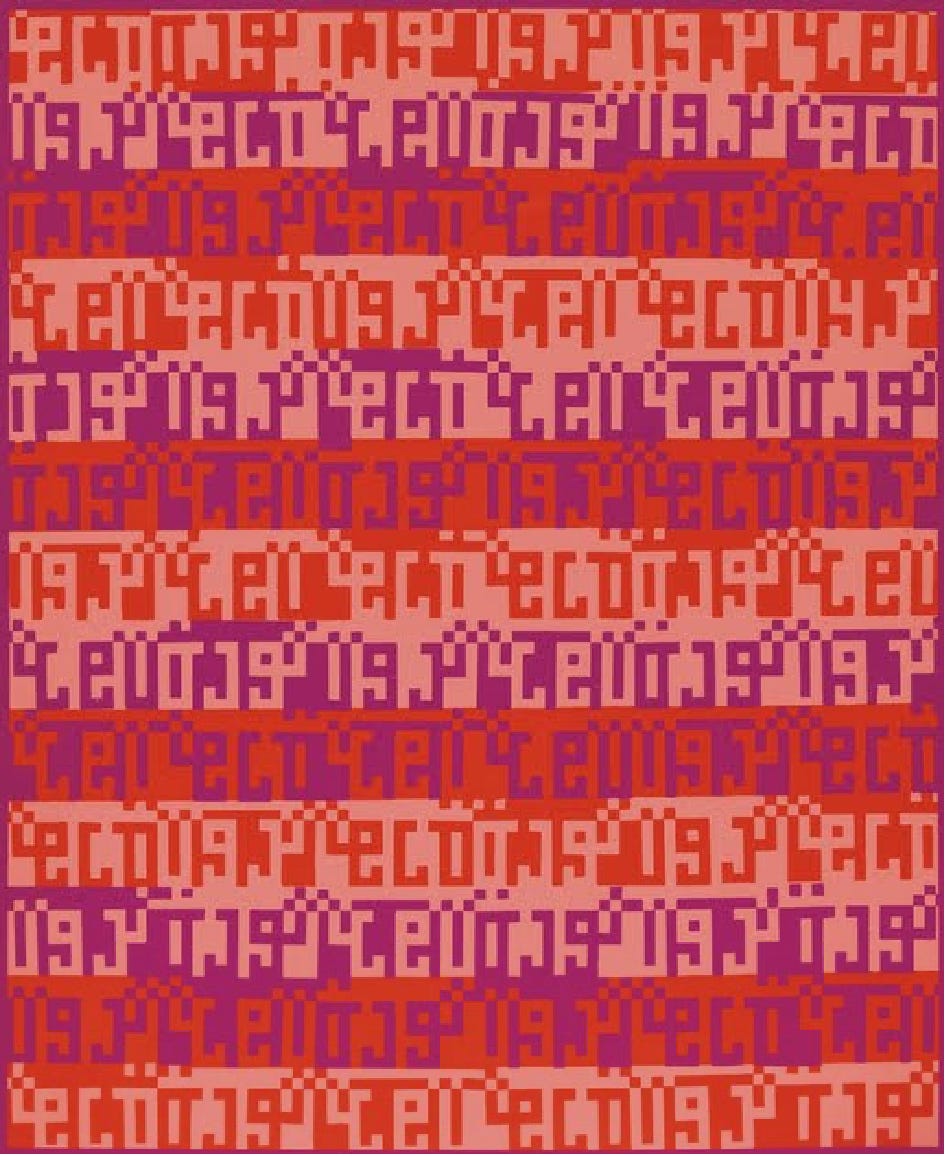

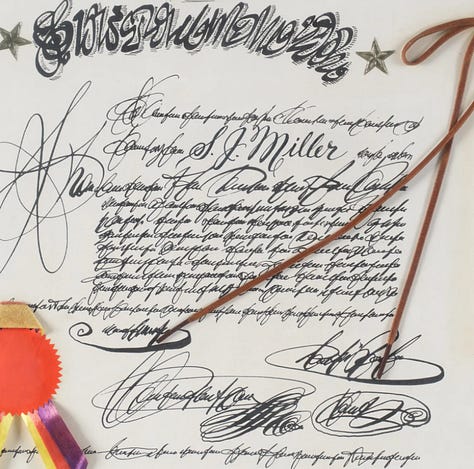

“His early text-based work was an influence on the development of the contemporary street art trend known as calligraffiti—a blend of Arabic writing and Abstract Expressionism, in which text is aesthetically altered to create abstract compositions that transcend literal meaning.” 1

Here’s an example of Calligraffi. I’m in awe:

In an interview with the National, Boullata said: “I don’t think that you can lead a purely creative life or a purely political life… Everything is interrelated, even if we are unaware of that fact. When artists in Gaza were under bombardment and looking after their families, they still kept on thinking about art.”2

Boullata literally wrote the book on contemporary Palestinian art: “Palestinian Art, From 1850 to the Present” with a forward John Berger. It’s backordered, but you can reserve a copy here.

Hazem Harb

Hazem Harb is another Gazan native currently living in exile. He was born in Gaza in 1980 to a family of eight. His mother was a seamstress and stylist and introduced him to artwork and a creative practice early in his life. He later moved from Gaza to Rome to study and now lives in the UAE. Traditionally, Harb’s art practice is based in collage. He layers various materials like papers, photos and ephemera to layers to suggest a story always related to his Palestinian identity.

But since the war started, Harb says he “can’t make art in the same way. He has stepped away from collage and started creating more expressive works using materials such as charcoal and gauze.’ 3 While multimedia, these gauze pieces function very much like drawings, and up close are sets of very thin lines, together forming a ghost like image.

I learned while researching Hazem’s artwork that the word Gauze, that finely woven fabric used for dressing wounds, comes from the Arabic word “Ghazza” which in English is pronounced “Gaza”. It’s where gauze was invented.

Hazem also started drawing large scale charcoal drawings. They remind me so much of Goya’s Disasters of War. Urgent and palpable and terrible and impossible to look away from. On Harb’s instagram page, he speaks about the recent bombing of his family’s home in Gaza, and his elderly father’s imprisonment, providing powerful context for the work above and below.

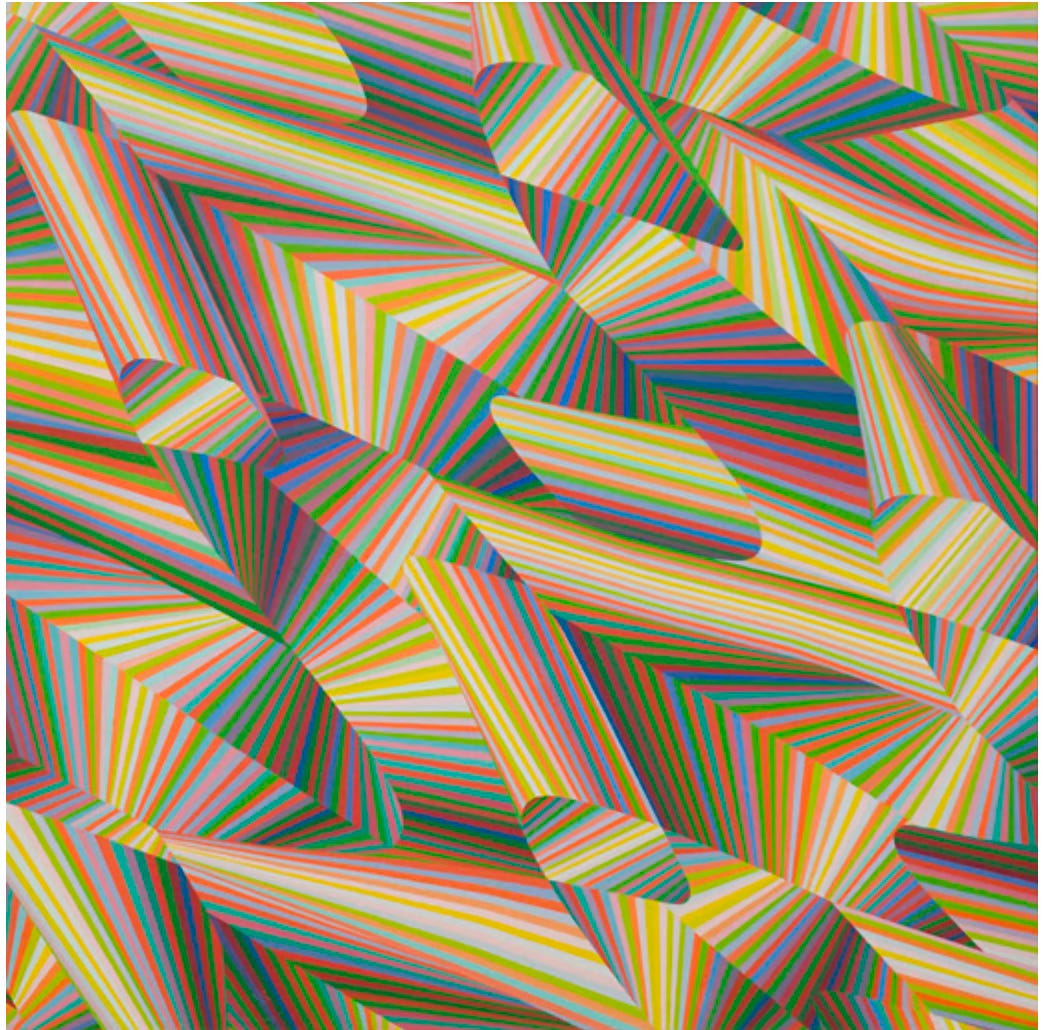

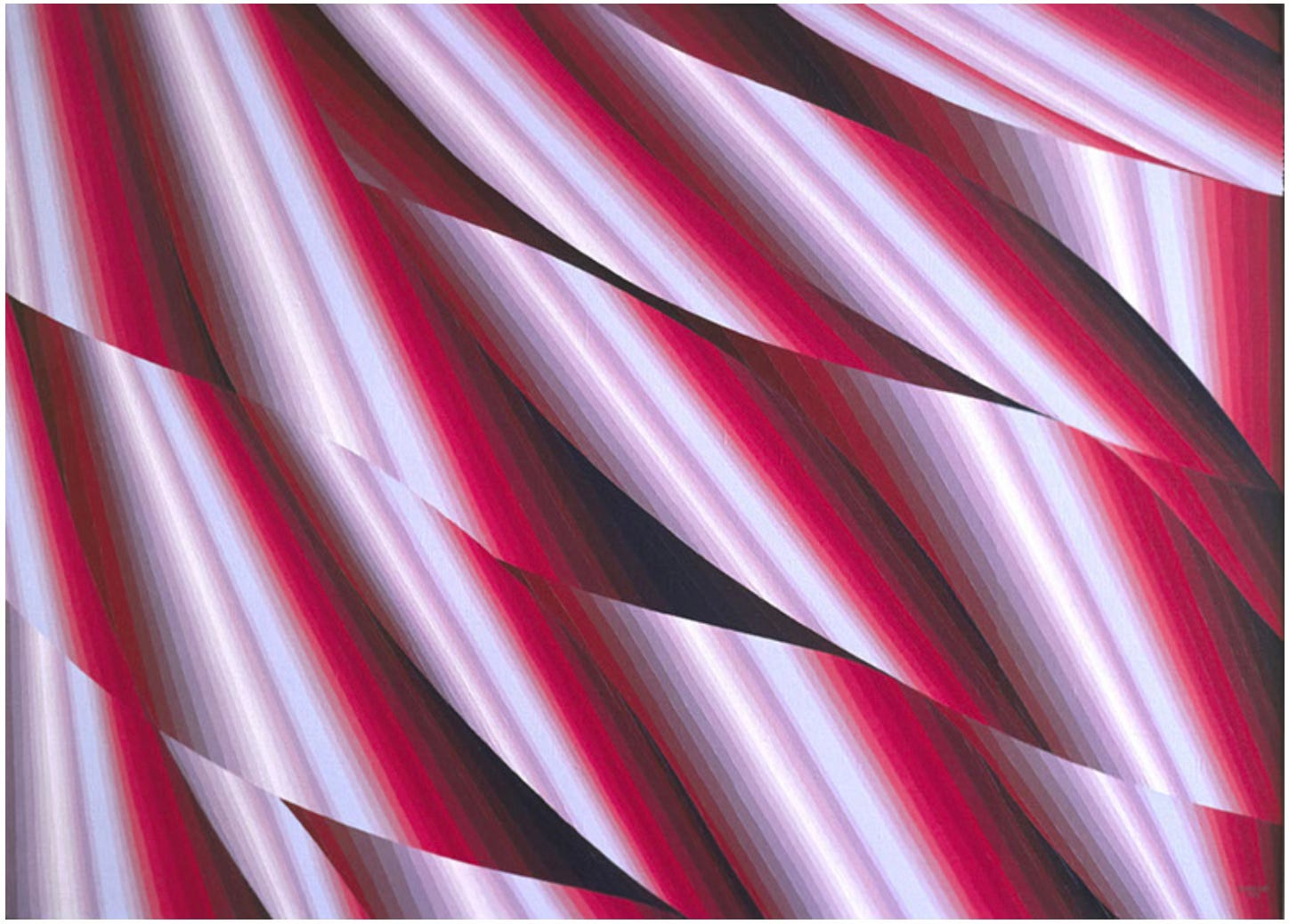

Samia Halaby

Born in Jerusalem in 1936, Samia Halaby is a Palestinian abstract painter and scholar, and makes the most stunning artwork in various mediums. STUNNING. How I have not known of her work until now?! I’m so happy I do now, and I’m thrilled to share her work with you.

When Samia was eleven, she and her family were displaced from Palestine and moved to USA’s midwest. After studying art, she moved to New York and found an unwelcoming art world, which she attributes to her heritage. But she persevered, eventually becoming the first full-time female associate professor at the Yale University School of Art in 1973.

This video below is a phenomenal 8 minute video about her life and work, and I highly suggest every GUT member watch it. From paintings to early digital work on the computer to sculpture, to her thoughts on memory and looking, on identity and longing, she is a total inspiration to me, and I’m sure she will be to you, too:

For the past three years, Samia Halaby had been hard at work on a major retrospective exhibition scheduled at Indiana University, her alma mater. It was set to open last month (Feb. 2024.) However, without any discussion, the University abruptly cancelled the exhibition. They sent Samia a letter informing her that her painting would be sent back, then refused further conversation. Samia said she believes it is because of her identity, and that she made a post calling for a ceasefire on her instagram account. Later, the administration called the show a “lightening rod” and they didn’t want to introduce controversy at the school.

In response, a University of Indiana math professor, Elizabeth Housworth, “used her own money, and with support from private donors and Halaby's studio... organized "Samia Halaby Uncanceled." It's a one-day exhibit that features artwork, videos and documentaries about Halaby's life and career.”4

The exhibition sold out immediately.

Here are a few images of her paintings. When you look at these, keep in mind the themes of calligraphy and color and place. I think we can see a real through-line…

Note from me: what initially sucked me into Samia’s work were her earlier paintings, from the 70s. Looking at these made me run and grab my colored pencils.

All so inspiring, right? So much to see, and to learn.

Which takes us to the assignment part of our program. You might want to grab some colored pencils yourself right about now.

Assignment: Drawing in their shoes

So we just looked at the work of three very different artists who all use the elements of drawing in their work (even when they are painting.) The major elements I notice are line, shape, positive/negative space, and of course color (which technically isn’t an element of drawing but NO RULES IN ART.)

Today I’m offering you a choice. I am giving you an assignment inspired by EACH ARTIST, and you can choose one. Or two! Or do all three! One, two or three, they are all deep dives into learning about how these artists made the work they did. Which is our drawing equivalent to walking in their shoes.

I am going to walk you through how I did it, and you can follow suit or go rogue. No rules in art. What matters is that we are looking closely, and learning through drawing.

1. Kamal Boullata: Abstract calligraphy drawing

The primary elements of Kamal’s work we address in this prompt are Symmetry and Composition.