Hi friends! So happy you’re here. Turns out last week was a great time for some Ruth Asawa flowers. It was amazing to see the hundreds of flowers you all created in our art share/community chat. We were so happy to collaborate with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Asawa estate to share Ruth’s flowers with you. This week, our collaboration continues with a firsthand look at her family life and home.

Ruth Asawa at Home

In last week’s lesson, I shared that I had the pleasure of walking through Ruth Asawa’s retrospective at SFMOMA with her grandson, Henry Weverka, who is also head of the family-run entity dedicated to preserving and protecting her life’s work.

I originally met Henry after speaking with Asawa’s son Paul Lanier a couple years ago. I interviewed Paul to learn more about growing up in an artistic household. I was curious how artists cultivate creativity in their own home, and if/how that impacts their children over time. (AKA, how to grow a creative human.) When I published the piece, I had not asked for permission to feature a couple of the images (SORRY!) and was quickly contacted by Henry to make it right. He was gracious and supportive, and loves what we are doing at the GUT, and we struck up a nice rapport. (And I fixed all the permissions. Never again, Henry! Promise!)

Flash forward, shortly after the exhibition opened, Henry generously walked me through the show and shared some wonderful insights into the daily home life of his grandmother, the artist Ruth Asawa.

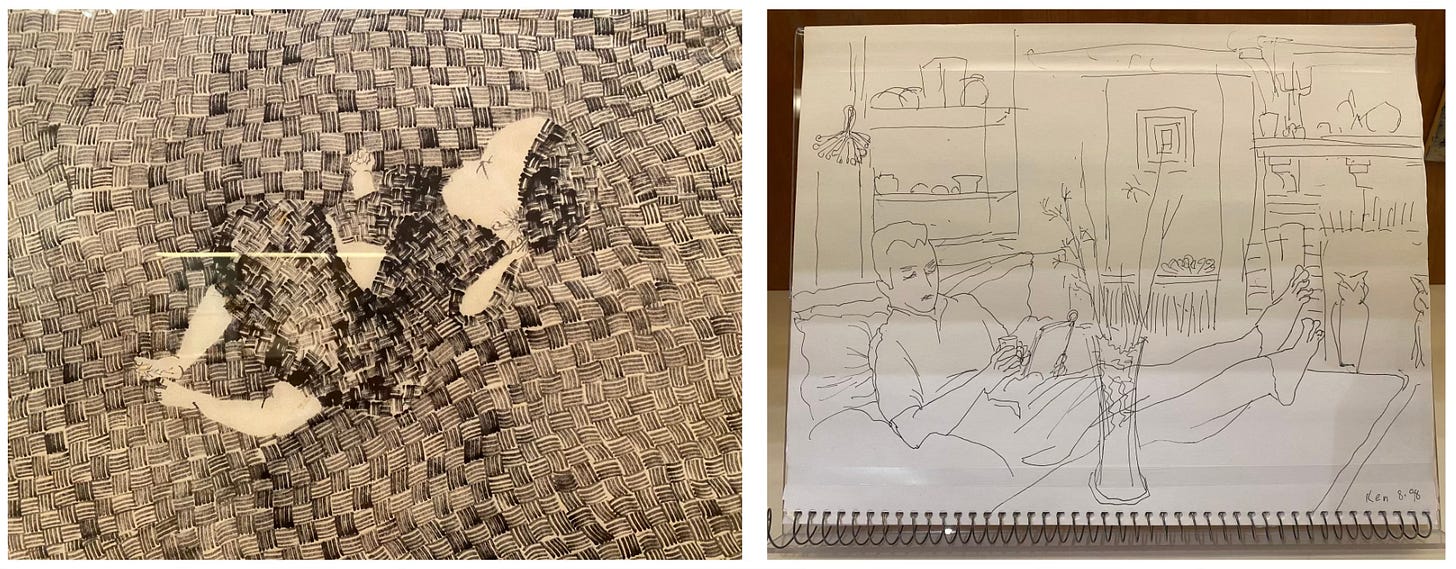

One of the things that stands out in the SFMOMA exhibition is an installation in one gallery that really gives you a sense of her home. A huge image of her actual home hangs on the wall like a window into the past, and the living room experience they created makes you feel like you are almost there. They installed wood panelling on all the walls, a rug and mid-century furniture, and included bookshelves packed with her artwork. Several of her wire sculptures hang from the ceiling so you can get a real sense of what it would feel like to live with them, just like you see in the photo.

You become a visitor in her home.

Henry said,

“When I was a kid, there was people always coming and going, artists, eccentrics, all these different people. She really, she didn't discriminate based on race or gender. It was like she really wanted to have an artist community.”

Ruth Asawa and Albert Lanier moved to Noe Valley in 1961, and that’s the house Henry associates with his grandparents. Asawa had a dedicated studio, but, he told me,

“Really she worked everywhere. … If you went to her house before dinner time, there would be origami paper folded, a sketchbook, maybe a little wire piece she was working on down on the kitchen table. And then she was an amazing cook, and she would make food for everybody. And all the artwork, all the art material would shift over to the end of this 11-foot butcher block table. Everybody would eat and then go on their way. And then slowly but surely [the artwork] would come back over.”

Ruth Asawa had six children with her husband Albert Lanier. Henry said:

She said she chose to keep her studio at home so that her children could see her work and understand what she did, and then she could help them with anything they needed, including a peanut butter sandwich.

At the same time, she was an artist. She never stopped making work.

“She was so busy that as a child, if you wanted to talk to her, you'd go help her coil wire while you talk to her. It's like, mom, can I go to so-and-so's house after school today? And she's like, okay, give the spool back, run away. Give the dowel back. And when she's working on tied wire, if you want to talk to her, you would pass her [wire] ties… she would bend the wire and tie 'em off by hand. I mean, you saw how little her hands looked, but she was incredibly strong.”

Helping Ruth with the wire wasn’t the only role of the kids in artmaking. Often, creation was a collaborative, family endeavor that challenged the kids and taught them craft and resilience. Here’s what Henry had to say about the carved front doors to their home (above):

“Shortly after they bought the house in 1961, Asawa enlisted the help of my uncle [Xavier]'s labor and [my aunt] Aiko both 11, [along with] Hudson, who was nine. [She] gave them blow torches and chisels, and they helped her carve these doors. And so what I love about 'em too is you can see some of them were shallow or less perfect. And those are the ones that I believe were done by the kids. But again, it was part of the practice. It was teaching her children how to use tools, how to work with material.”

He recalled spending time with his grandmother as…

“art camp! I would walk through my backyard and the big room and ask “What are we doing today“ … In the essay that Janet Bishop wrote, she interviewed Lilli [Ruth’s granddaughter], who's an amazing artist. And she said that one thing that she would do with my grandmother is they would go shopping, buy an eggplant, and then they would draw or paint the eggplants. After they're done drawing them, Asawa would take the eggplants to cut it up and teach her how to make eggplants with Japanese noodles. It was like a double lesson.”

With Henry’s deep, personal knowledge of Ruth’s life and work, and his commitment to the legacy of her art, it makes perfect sense that he’s taken a role as president of Asawa’s estate. It’s a huge responsibility, archiving and managing every single piece of work created by Ruth over the course of her life, as well as intersecting work by other artists. Going through all her work has given him the chance to get to know her better, and reconsider their relationship.

“My cousin Emma and I were archiving and digitizing all of her whole photo archive. So Imogen Cunningham prints, Laurence Cuneo prints, all these different things. And so we're folding the picture corners where you take a square and you fold it corner to corner, and then you have a little flap. … And I'm sitting there with my cousin, Emma, and I was like, do you realize that Grandma told us that we were in origami camp, but she was just teaching us how to archive all her crap?!”

(LOL. Grandma’s gonna grandma.)

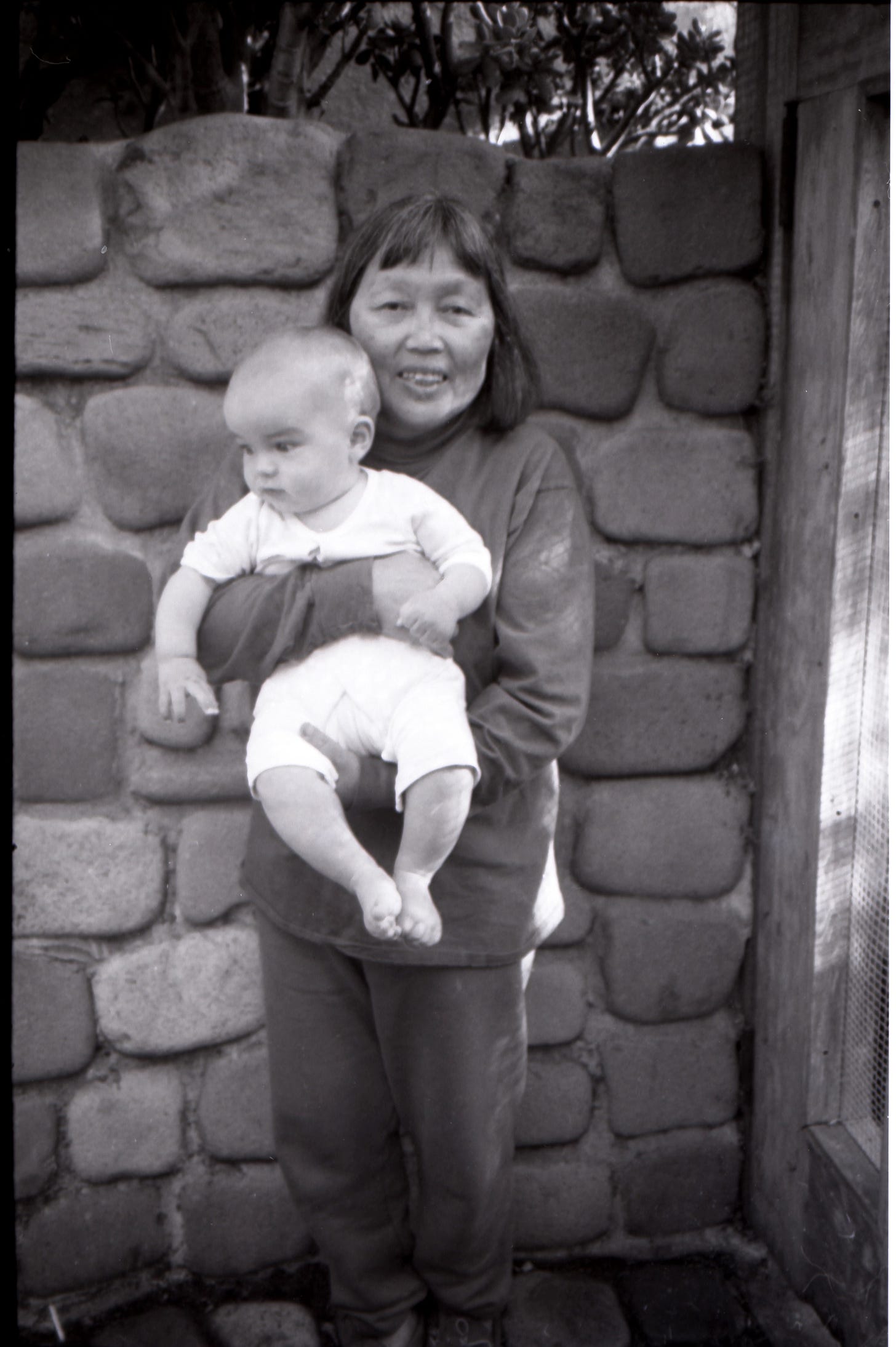

Henry carries on Ruth Asawa’s legacy within his own family, as well. A casting of his hands and feet from when he was a baby are in the exhibition (pictured above), a tradition he carried on with his own son.

Henry said,

“When I ask [my son] what are sculptures, he looks up. Because he always knows sculptures come from the ceiling.”

Such a delight to get to know Ruth a little better through the eyes of her grandson Henry. Thank you for sharing your time with us, Henry, and for all you do to protect the integrity of Ruth’s artwork for us all.

Alright, friends. Let’s put this thinking about family, friends, and artmaking and the home into practice. Let’s draw.