Heellllooo my wonderful GUT peeps.

I am happy to report I am finally off the sick bed/couch and nearly 100% back in the land of the living/talking. Thanks for your patience and well wishes. In an effort to pace myself a little better in 2024, let’s ease back into it slooowwly with a little housekeeping, then get started on a new drawing/looking/loving adventure.

GUT Housekeeping!

Info for newcomers/refresher for old-timers: I highly recommend popping into The GUT Intros to say hi and see who else is here. Interested in joining a GUT Drawing Zoom drawing hangout or a Local IRL GUT Drawing Group? Want to start one in your area? Info at the end of this email. (This is for GUT Community members only: gotta keep this info private, therefor safe.)

Where can I get help with the GUT? Art Auntie Kathleen is in the comments and GUT community chats welcoming everyone and answering your little Q’s about sharing artwork, etc. (everyone say “hiiii auntie kathleen!”) Kyle Ranson-Walsh can help with tougher tech or gift subscription issues and that kind of thing via email: Community@DrawTogether.Studio. Thank you K&K!

What about DT for KIDS? Looking for DrawTogether for young folks, too? DT’s awesome non-profit educational program DrawTogether Classrooms supports approx 300,000 learners of all ages around the world (that’s over 10K classrooms!) Educators in all learning environments can access the full curriculum, videos, podcasts and more FOR FREE. As a subscribing member of the DrawTogether Grown-Ups Table, you help keep that available for all. TYSM!

Now let’s get on with the show.

How to See More with Dorothea Lange

I’m giving a talk in a couple weeks at the National Gallery of Art in DC about my work and the photography of Dorothea Lange (register here!) It accompanies a project I’m doing there called DrawTogether Strangers where I invite strangers to draw each other for one minute without looking down. In other words, I trick them into looking closely at one another, and allow themselves to be looked at, too. This drawing project, and all my work, is deeply informed by Dorothea’s photography, her social practice, and ethos.

Who is Dorothea Lange

For those unfamiliar with her work, the photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) used a camera to look closely at people and the world. She published her work in newspapers, magazines, academic and government journals and publications, books and, eventually, museums. Beyond art and aesthetic, her work had deep, lastings ocial impact: it influenced awareness, public opinion, government funding and state and national policy. Her work changed the way people saw the world, and the way people saw themselves.

“The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” - Dorothea Lange

(“The same is true of drawing!” - Everyone at the Grown-Ups Table)

You may be familiar with Dorothea’s photographs during the depression, specifically her photo “Migrant Mother” - a photo of a mother and her children at a pea-farmers camp in California. (There is a heck of a irksome story behind this photo she took of Cherokee woman Florence Owens Thompson and her kids, and it points to some real important learning opportunities for her and me and all of us. But I’ll save that for a later dispatch.)

More than her craft, I admire Dorothea’s the care, curiosity and fearlessness that’s expressed in her work. Her portraits went beyond a person and told a story of the social, economic and power systems in which they lived. Her documentary portraits highlighted an individual’s dignity and strength within struggle. She captured the best of people in the worst of times.

In DrawTogether and The Grown-Ups Table, I try to get us to focus on the process of drawing, and not as much the outcome. On slowing down, paying attention. Taking chances, being brave, making mistakes, looking closely and connecting deeply with what and who we are drawing. Again, on PROCESS.

So I wonder, what was Dorothea’s PROCESS of making a photo? What lifetime of experience did Dorothea bring to bear on her work, and what was her process in the moment of making the work?

“Seeing is more than a physiological phenomenon… We see not only with our eyes but with all that we are and all that our culture is. The artist is a professional see-er” - Dorothea Lange

Today, we are going to focus on one aspect of Dorothea’s process that I didn't know much about: how writing helped her see. We are going to explore how Dorothea used captions in her work and what we here at the GUT can learn from making CAPTIONS for our drawing.

But first, a little on the “process behind the process”. Let’s learn a wee bit about Dorothea’s life.

Who was Dorothea’s Lange?

Born in a suburb of Hoboken, New Jersey, Dorothea contracted polio at 7 years old, leaving her with a limp. She cited the disability as one of the two most important events in her life. The second was was the breakup of her parent’s marriage, which prompted the move of her mother, herself and her siblings to a poorer neighborhood in New York City at 12 years old. Attending school in the struggling lower east side she walked the streets closely observing the world around her. She learned to don what she called her “invisibly cloak”: she could look at people but go unnoticed herself. She learned to blend in. Later she attended an upper class high school… she grew up moving between worlds and could make herself comfortable anywhere, with anyone. She was strong, defiant even, and intensely curious. Always observing, she developed an interest in photography. Later, finding herself stranded in SF while traveling with her best friend -they got pickpocketed and lost their money and passports! - she began assisting at a photo portrait studio. And that’s where she learned her craft.

Flash forward: Dorothea built a successful career as one of SF’s premier portrait photographer. Her clients were the wealthiest most powerful socialites and arts supporters. She married the swashbuckling painter Maynard Dixon, had two kids with him, travelled around the country with him taking photos (often leaving the kids behind in foster care.) Then came the depression. She turned her attention (AKA her camera) away from the wealthy and towards the people standing in breadlines outside her studio in SF.

A quote from Dorothea on the photo above: “[White Angel Breadline] is my most famed photograph. I made that on the first day I ever went out in an area where people said, ‘Oh, don't go there.’ It was the first day that I ever made a photograph on the street.”

A UC Berkeley economist and sociologist named Paul Taylor saw Dorothea’s photographs and invited her to travel with him and document the country during the Great Depression. He knew images would make a greater impact than statistics and reporting alone. Together, he believed they could capture the minds and hearts of lawmakers and create change in politics. Dorothea wasn’t a political person at the time, but she agreed and they began working together. They would quickly fall in love and develop a personal and partnership that would last a lifetime. And with that partnership, Dorothea would create an entirely new form of documentary photography.

The influence of Paul, a sociologist, on Dorothea’s photographic work was tremendous.

“How?” You ask?

Well, several ways, but one simple one: Paul Taylor got her to start writing.

“Write? Write what?” You ask?

Captions!

“Captions? Um.. What do captions have to do with images? Who cares about captions??”

I know, right? Who cares about captions?? But bear with me! WE should care about captions, GUT. As drawers, we can learn from writing and caption making, too. I’ll tell you why:

A visual artist can use writing to see better. Writing about what we see can help an observer see more. And reading about an image can help an observer see more in an image. Dorothea’s process of captioning - how she recorded observations with text, and how she assigned text to images - helped her SEE MORE and SHARE MORE with viewers.

We can apply those lessons to our own practice of seeing, too.

I’m going to give you an example of how this played out in Dorothea’s work, and then we will get into our project using these tools ourselves.

Field Notes & Captions & Telling a Visual Story

What is a caption? A caption is text that accompanies an image to explain and elaborate on a published photograph. Generally speaking, captions are usually a line or two. In Dorothea’s case, they ended up being a LOT LONGER at times. :)

Paul Taylor taught Dorothea how to observe, write, and develop captions like a sociologist. Essentially, he taught her how to take field notes. He taught her to pay close attention and take notes not only at the facts of her subject but the whole scenario. How to interview her subjects and learn about their conditions. How to get the whole story. And then how to combine words and image to tell a more complete story.

Let me give you an example:

In 1939, Dorothea Lange (and Paul Taylor most likely) spent a day in Person County documenting a sharecroppers home and family. Here are her field notes, or “general caption” she recorded during and after her visit.

And here are are a few photos from the day. You can see she pulled the specific captions from the longer General Captions/field notes.

“All photographs—not only those that are so-called “documentary”... can be fortified by words.” - Dorothea Lange

Here’s some other field notes from another journey she took with Paul…

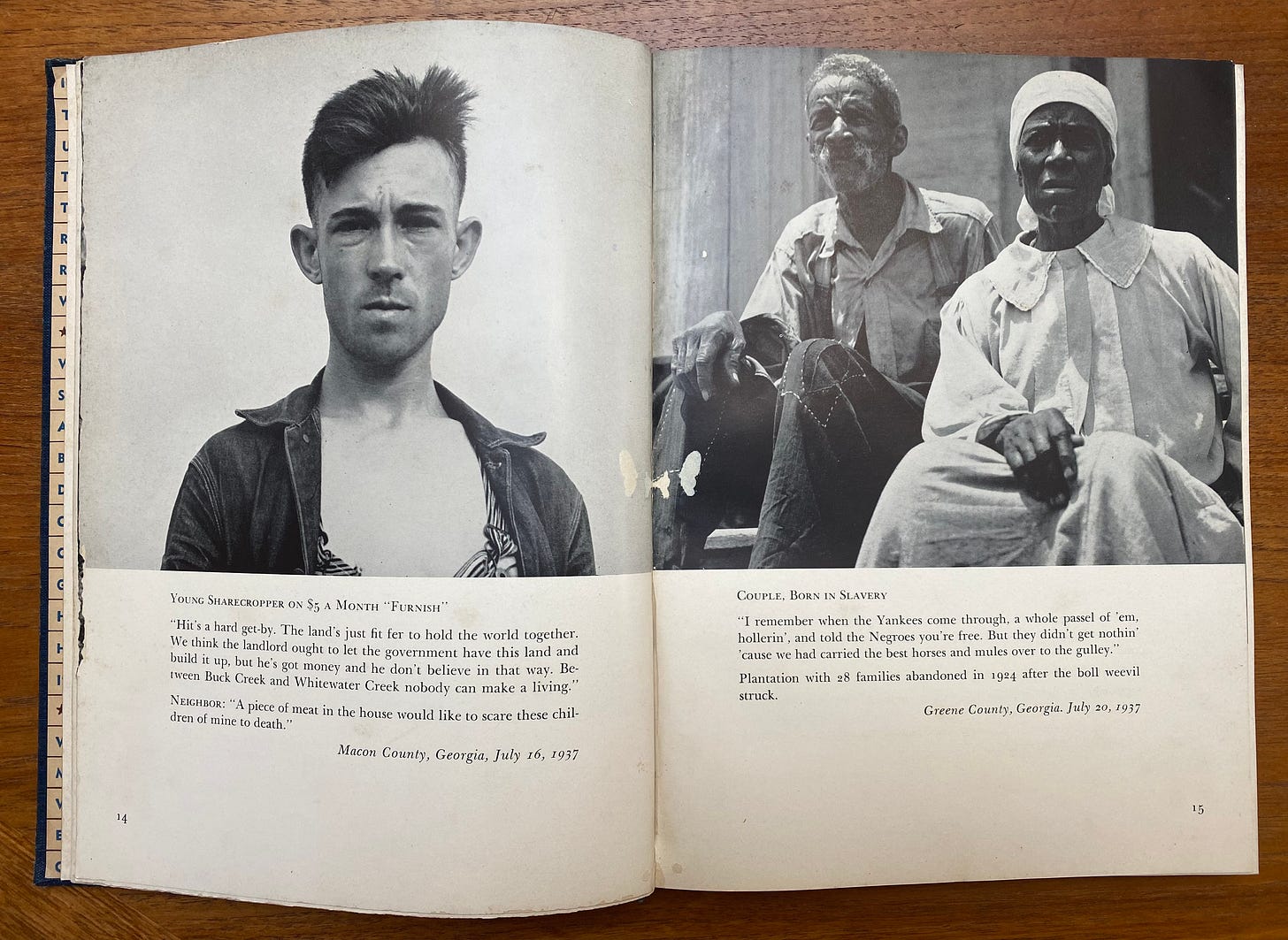

She and Paul also combined their photos and text in a groundbreaking book titled America Exodus. The boo synthesizes art and social science in a way that had never been done before. It centered the words of the subject.

Dorothea said, “Every photograph… belongs in some place, has a place in history—can be fortified by words,I’m just trying to find as many ways I can think of to enrich visible images so they mean more. “ The words and image create a story more than they could on their own.

This process of captioning helped Dorothea SEE MORE. It forced her to spend more time looking and engaging with the people she was photographing, and helped her see what and who was actually in front of her, instead of seeing what and who she expected to see.

Writing captions helped Dorothea learn how to see.

Now let’s explore how they can help us do the same with drawing.

Assignment: CAPTIONS for LOOKING CLOSELY

Today we are going to make a drawing and create a caption in the style of Paul Taylor/Dorothea Lange’s General Captions. The goal of this is to learn to see even more than we do when we draw, then bring the two together to tell a story.