Just jumping straight into it because GUESS WHAT, FRIENDS??

We are 100,000 Subscribers Strong!

This is a huge milestone for DrawTogether, The GUT, and for all of us! Thank you everyone who has been drawing, looking, and loving with us since day one - and to those of you who joined us as recently as today. DT is more than drawing lessons, it’s a practice. It’s a way of life. We are a community. Together, we are a movement. ❤️✏️

Let’s keep it going and growing.

That was some good cake!

Y’all seemed to EAT UP last week’s lesson (sorrrrrry 🙄.) Wayne Thiebaud’s cake drawings are delicious, and judging from the hundreds of drawings you made and shared it seemed like you enjoyed drawing cakes, too. If you make it to the Bay Area, be sure to check out the Wayne Thiebaud exhibit at the Legion of Honor.

After indulging ourselves with cake last week, let’s move our bodies a little! For the next two weeks, we are going to focus on the classic drawing subject: THE BODY. But with a twist! We are welcoming Guest Artist and Author Bonnie Tsui to talk to us about the role of muscle in art and life, and help us consider how we can involve it — and our whole bodies — in our drawing practice.

The Artist’s Body

“We all have muscles, and we all occupy a body, and we all have the capacity for potential, strength, and change that muscle allows us.” - Bonnie Tsui

As visual artists, when we think about how we use our bodies to draw, we often focus on our eyes and our hands. But if you’ve been drawing with me for a while, you’ve heard me say this before: ”We draw with our whole bodies.”

There’s no better person for us to learn from about the interplay of drawing and our bodies than writer Bonnie Tsui. You may be familiar with her critically-acclaimed books Why We Swim and American Chinatown as well as her children’s book, Sarah and the Big Wave, and she is a frequent contributor to The New York Times. But what a lot of people don’t know is that in addition to being an author and athlete, Bonnie was raised by an artist, and is an artist herself.

Bonnie’s latest book, On Muscle, is both informative and moving — it is the work of a gifted storyteller (so add that to artist and athlete!) She explores the science of human anatomy and muscle, but it’s their role in people’s lives and our ideas of ourselves that make up the heart (or should we say the meat?) of the book. Bonnie invites us into her family home where art and strength were intertwined, and she challenges typical narratives of ability and physique through the stories she includes.

On Muscle comes out on April 22. You can pre-order it here.

I first met Bonnie through the SF writers community, but really it was through surfering. I don’t surf, but back in the day, she and my ex Caroline would meet up before dawn to surf at Ocean Beach. I keep artist’s hours, so often I’d just be waking up when Caroline would just be getting home, offering impressive reports on Bonnie’s surfing. Bonnie and I bonded over drawing and art, and her creative kids were part of DrawTogether during the pandemic. I’m delighted to share her latest book with you.

Without further ado, here’s Bonnie, and the Art of Muscle!

Q&A with Bonnie Tsui: On Muscle

Wendy: Bonnie, thanks for talking with us. Can you tell us a little about the origin of your new book On Muscle?

Bonnie: My dad was a professional artist, and a martial artist—he still is! My brother and I grew up in his downstairs studio. As kids, we were immersed in art and exercise. Because of that education, form and function always went hand in hand for me: yes, the muscular body was beautiful, but it also had to work, to support all the things you wanted your body to do. The body is beautiful because of what it can do. I wanted to write a book about muscle and movement that continued the conversation of the body that started with Why We Swim—to explore not just what muscle is but what it means to us, in art, culture, science, and society.

Wendy: What do we take for granted about muscle? What do you want us to know more about - and why?

Bonnie: Muscle is quite literally the stuff that moves us—it attaches to our bones and helps us get around. Most people know that. But muscle is also an endocrine tissue, which means that it releases signaling molecules—called myokines—that travel around to other parts of your body to tell them to do things, including your brain. When they arrive at the brain, they regulate physiological and metabolic responses there, too. Which means that myokines have the ability to affect cognition, mood, and emotional behavior—kind of like a love letter from your muscle to your brain. I love that.

Wendy: How did learning about muscle change how you see your own body?

Bonnie: I learned to appreciate my body so much more. What it’s capable of. How we’re changing all the time, and how we have to take care of our bodies, for them to work dependably and well. Muscles have the remarkable ability to adapt and flex with us—as we grow and recover, as we get older. Muscle is change. I think that’s a philosophy of muscle that is really a philosophy of life. I find that so profound.

Wendy: Throughout this book, you talk movingly about your father as an artist and Michelangelo’s work on the Sistine Chapel. How did the process of writing this book affect your relationship with art, both as a viewer and a maker?

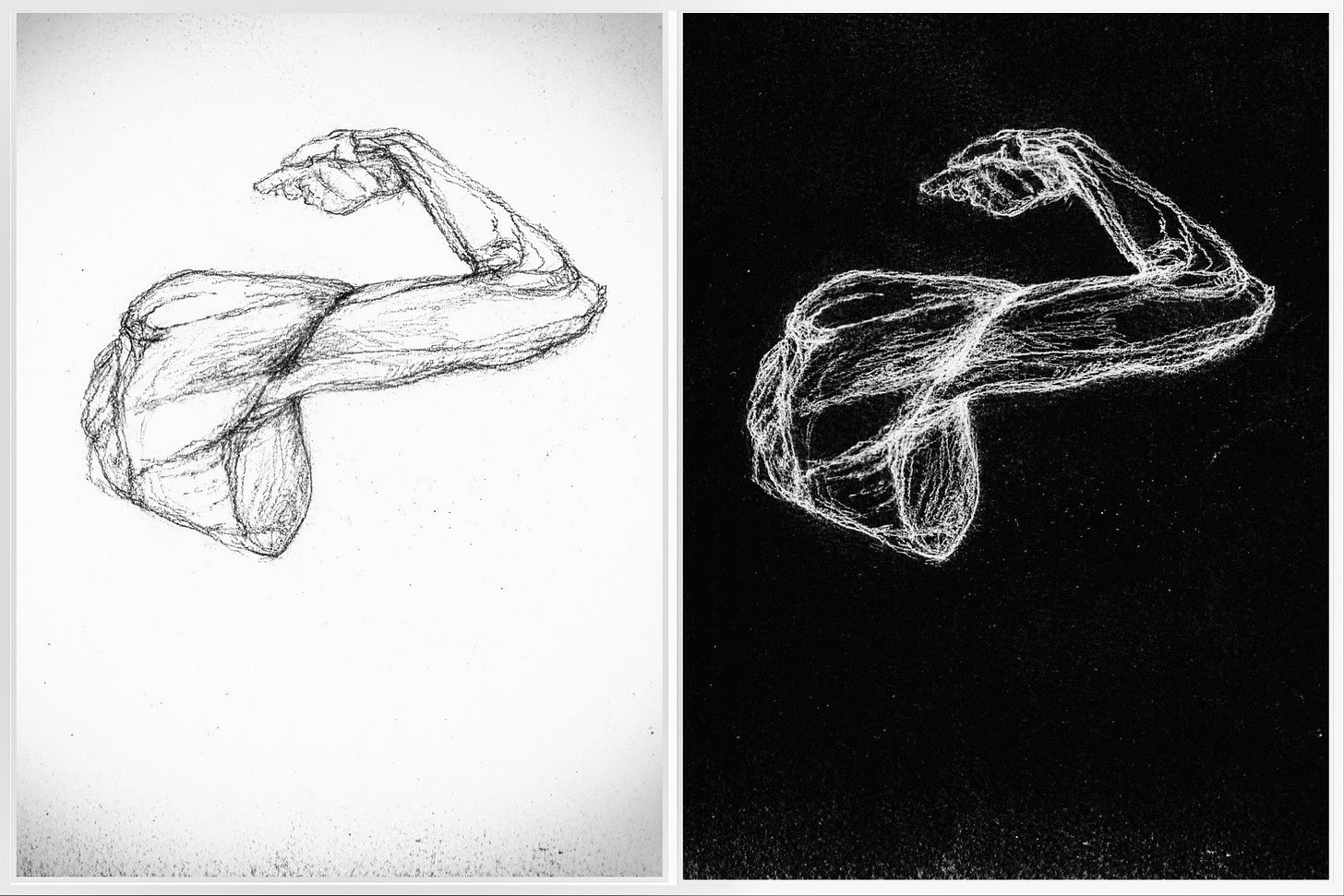

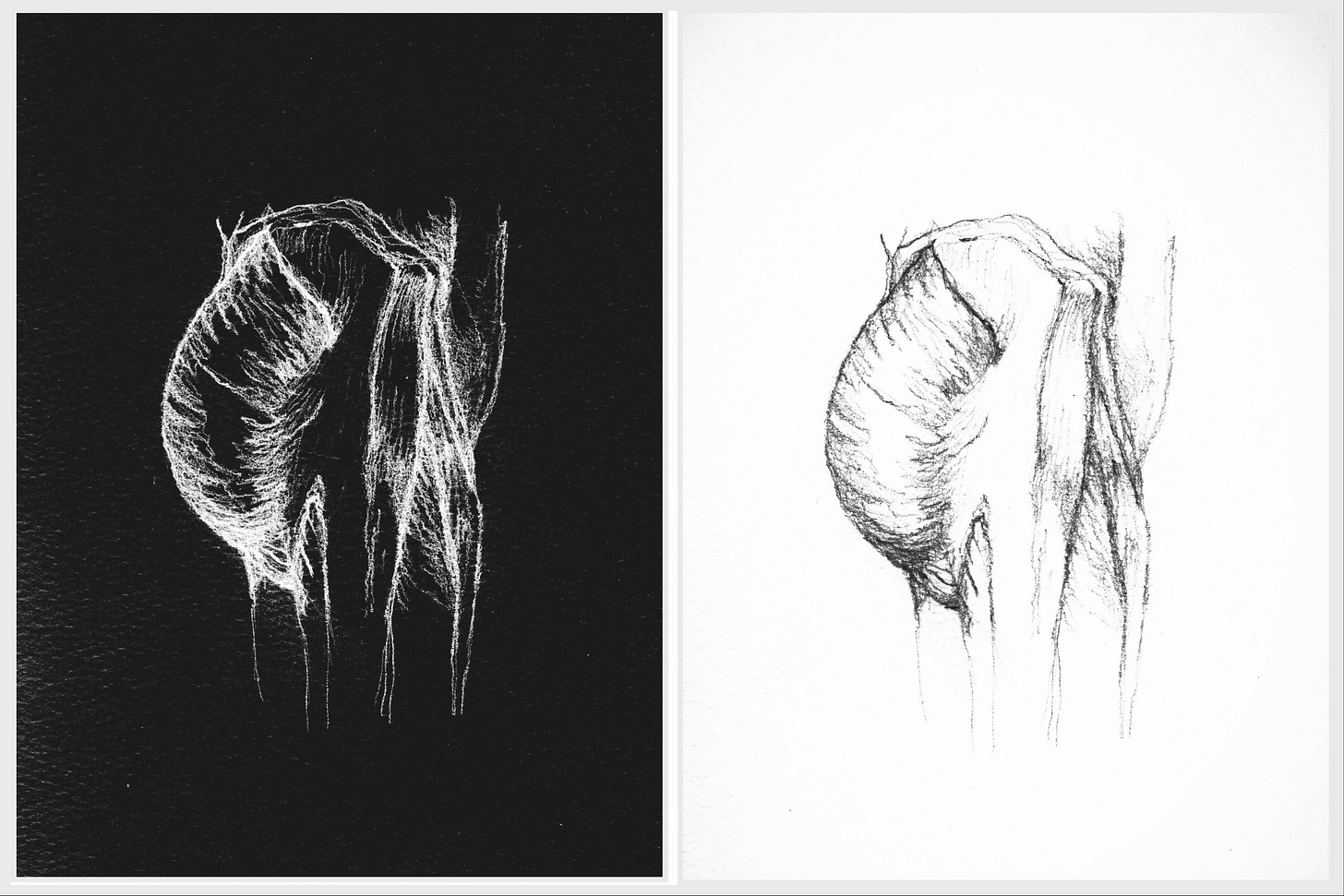

Bonnie: I loved the opportunity to think about and make art again. Art was such an integral part of my identity, right up until I graduated from college and decided to pursue writing instead of visual art. It meant so much to me to get to make art again as part of my work, as part of the exploration of what muscle is, and what it means to us as human beings. I also loved how making drawings of muscle—tracing the line of a shoulder, say, or the fibers of a glute—was a different way of understanding, of looking, of making meaning, with my actual hands and body.

Wendy: Your book includes powerful stories of people whose bodies and identities aren’t frequently centered in discussions of strength and fitness. Tell us a little bit about why you wanted to include these stories.

Bonnie: It was always my goal to make people think about muscle in new ways, and in unexpected ways. My mom calls this the muscle book for people who don’t think they need to read a book about muscle—like her! And I love that. Because the reality is that we all have muscles, and we all occupy a body, and we all have the capacity for potential, strength, and change that muscle allows us. All of us.

Wendy: This week’s assignment comes from Bonnie and draws upon how all our muscles are connected. Take it away, Bonnie!

Assignment: Continuous Line (Blind) Contour

The artist Paul Klee’s famous phrase “a line going for a walk” conveys his idea that art — and drawing — is created through movement. Imagine you’re looking at a drawing of a dancer, caught mid-pirouette. The dancer’s movement? All muscle. The drawing itself was created by the movement of the artist’s hand across the paper. Also muscle. And you are appreciating the artwork by moving your eyes around the lines of the drawing. Muscle part three!! Every dimension of visual art engages our muscles, and reflects how we move through the world.

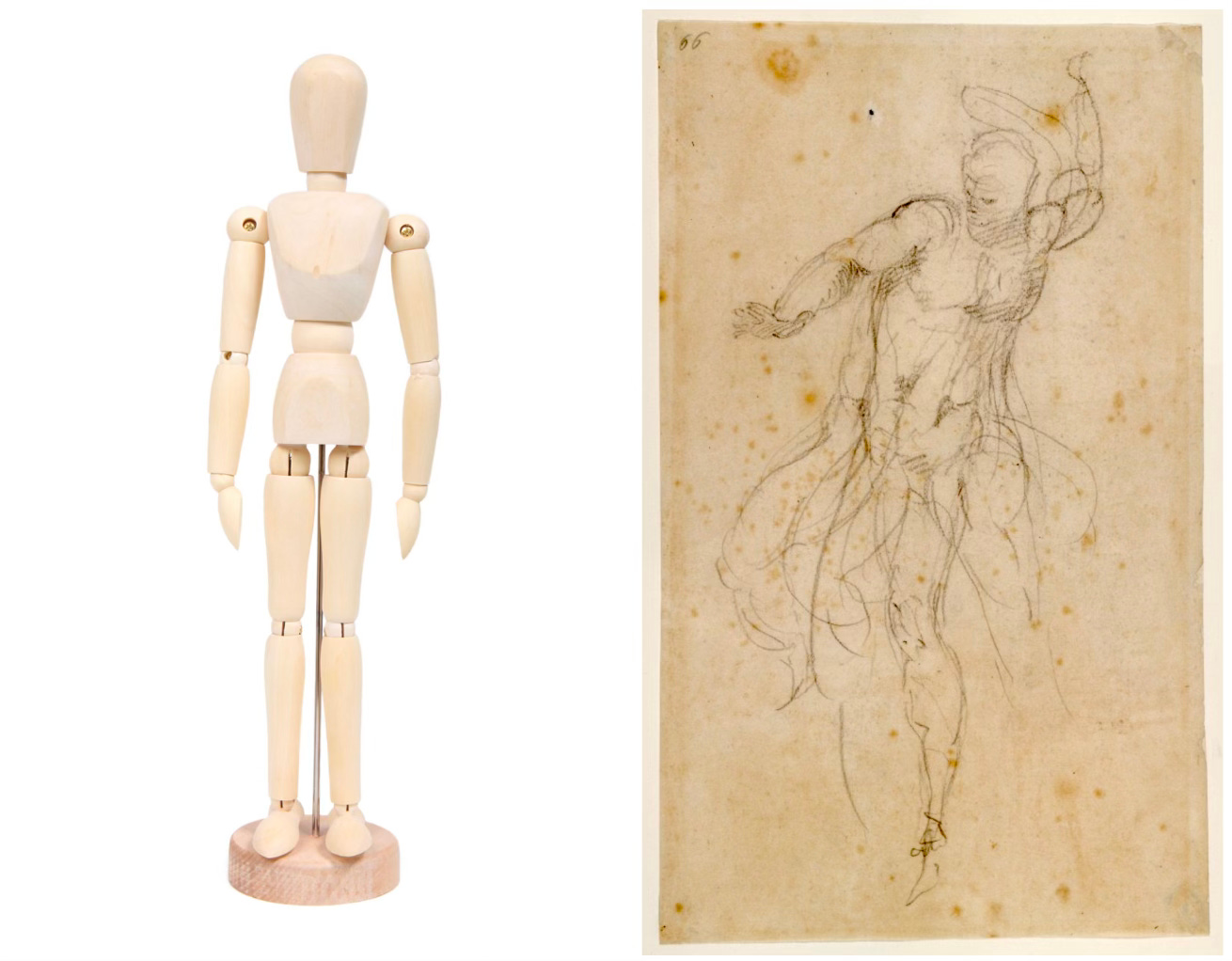

Often, when people are learning to draw anatomy, we use basic shapes as the foundation for drawing different parts of the body, like circles and rectangles. Imagine one of those figure drawing model dolls. They seem disconnected. This is not true.

When we begin to understand how all our muscles are connected, we see how our movements reveal a connectedness and wholeness within us. We can literally draw lines that bring our bodies together as a whole, and that is a far more accurate reflection the true structure of the body.

The act of tracing the line of the body on the page is a way of understanding with our eyes and our hands.

So let’s try it together.