Dream BIG with Christo & Jeanne-Claude

National Gallery of Art x DrawTogether Grown-Ups Table collab, Part 1

Hello my fine DrawTogether GUT friends and beyond.

Today is the first day of the National Gallery of Art x DrawTogether Grown-Ups Table collaboration. The National Gallery will share these lessons and assignments on their website as well. Wonder Art power, ACTIVATE!

As the National Gallery’s first Storyteller in Residence, I got to dive into their archives and talk with their curators, all to bring lessons and assignments back to us here at the DT GUT.

The National Gallery is sharing all this with their audience as well, so get ready for some DT GUT x NGA cross-pollination/collaboration. We’ll share our National Gallery-archive-inspired drawings in the chat and cheer each other on there, per usual. That’s the community aspect of this and you have to be a subscriber to access that, so to celebrate, today I’m offering 20% annual memberships. Get it while it’s hot!

The first three works we’ll be looking at are all in the prints and drawings collections, and we’ll be learning from Caitlin Brague and Angélica Becerra who work in the department of modern prints and drawings.

We’re starting off this series with a drawing very near and dear to my heart. It was made not far from the area where I grew up, and it’s endlessly inspiring and outrageous. That drawing is by installation artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

I asked the team if they would pull from the archives Christo and Jean-Claude’s GIANT sketch for their 24.5 mile long installation “Running Fence.”

They said yes.

Artist Spotlight: Dream Big with Christo & Jeanne-Claude

“The idea for all our projects, not only Running Fence, starts with sketches.”

- Christo

Christo (born Christo Javacheff) and Jeanne-Claude (Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon) rarely do anything small. As both artists and people, they dream BIG.

They were born on the same day in 1935: Jeanne-Claude in Morocco, Christo in Bulgaria. The pair met when Christo was commissioned to paint a portrait of Jeanne-Claude’s mother. Despite being from two very different worlds, they fell madly in love. Within a year, Christo had abandoned his painting, and they were making conceptual artwork together.

They didn’t have a lot of money, but that didn’t stop them from dreaming BIG. They used materials they found on the street, like empty oil cans. And they used their chutzpah, ignoring rules (as well as laws) to create installations that caught the art world’s attention.

Their first public piece together was Wall of Barrels - The Iron Curtain. To make it, they piled empty oil barrels between two buildings, completely blocking a street for eight hours. The two were almost arrested, but the work resonated with the public and got a lot of coverage. It set a course for their large-scale, conceptual interventions.

Their ideas, dreams and projects only got bigger from there.

If you can draw it, you can pay for it

They were interested in creating a daring aesthetic experience for people: imaging the impossible, then bringing it to life. And always in the face of challenges.

The work of art is a scream of freedom. - Christo

For example, their projects weren’t cheap. And in the true screaming spirit of freedom, Christo and Jeanne-Claude refused to work with patrons or public funding. They had to pay for it themselves. (We are talking many millions of dollars.)

So they created a unique, smart business model: They made and sold preparatory drawings to pay for each project.

It’s like Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s twist on “if you build it they will come” from Field of Dreams: “If you draw it, you can pay for it.”

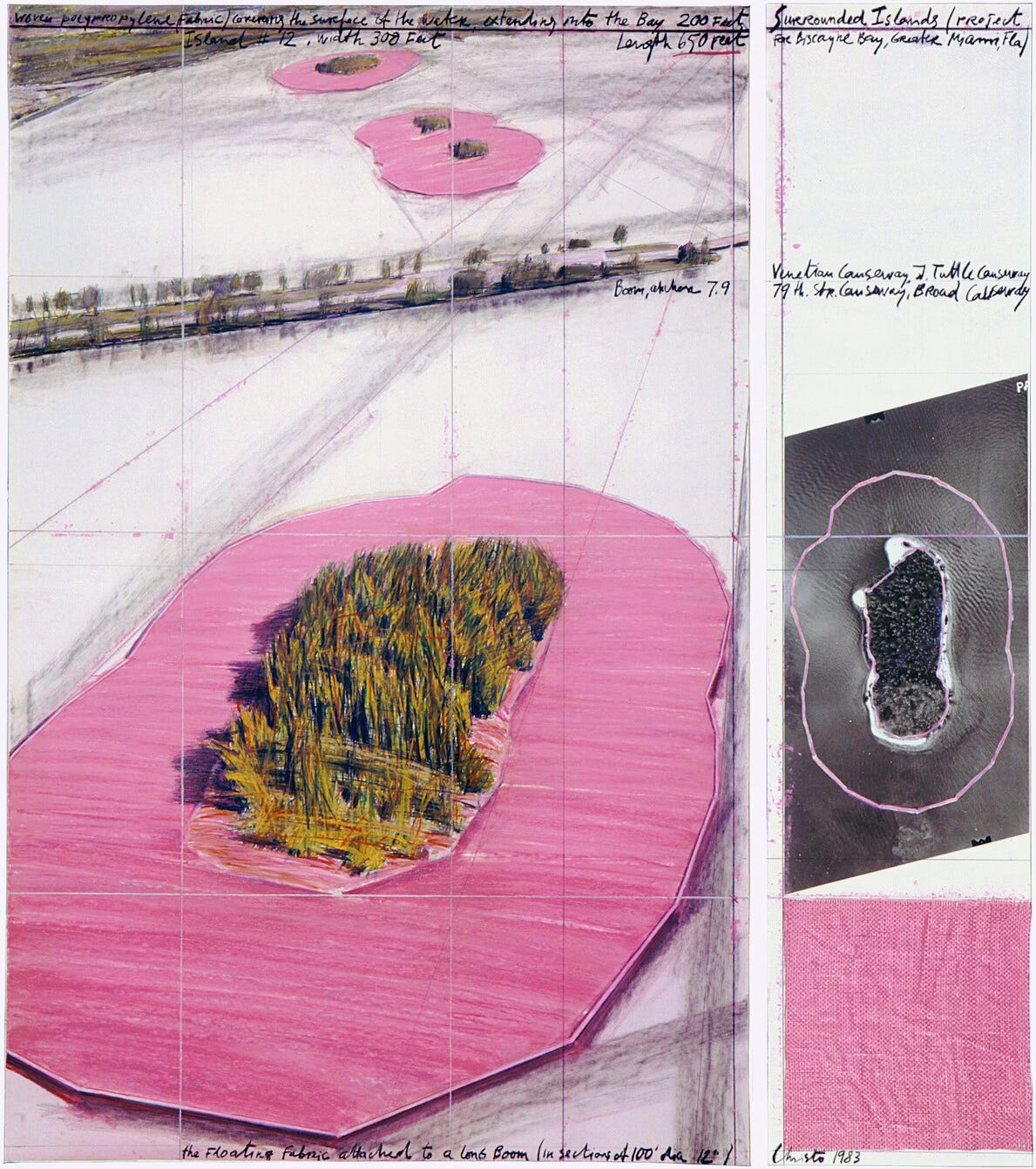

Below is a drawing for a work called Surrounded Islands. In 1983, Christo and Jeanne-Claude surrounded islands in Miami with pink fabric. The installation only lasted two weeks. The drawings that they created to prepare for and fund the project, however, still remain.

The drawing includes a color swatch of the fabric, an annotated map of the location, and a tight sketch for the finished piece.

The sketch and the finished artwork represent two stages of dreaming for Christo and Jeanne-Claude. They called these their “software and hardware periods.” During the software stage of creating when they would imagine and prepare. Hardware was the physical execution stage - what I call “production.”

This brings us to Running Fence - one of the duo’s most tremendous accomplishments, in both its software and hardware stages.

Creating Running Fence

The drawing above is a portion of the four panel drawing I looked at close up in the archives of the National Gallery.

In 1972, Christo and Jeanne-Claude began a 3.5 year effort imagining, planning, and creating the project Running Fence. This 18 foot tall, 24.5 mile long fabric fence that ran from Petaluma, California, right into the Pacific Ocean. It was on display for two weeks in September, 1976.

The project cost more than $2 million dollars at the time. (Adjusted for inflation, that’s upwards of $11 million dollars today.) And the artists paid for it by selling preparatory drawings that they made for the project (like the one above.)

The drawing I saw is HUGE, nearly 5 by 8 feet. It’s in the National Gallery’s permanent collection, thanks to the generous gift in honor of New York-based collectors Herbert and Dorothy Vogel (who are stories unto themselves.) It is a tremendous example of Christo and Jeanne Claude’s preparatory drawings.

It consists of four panels framed in plexiglass. Each panel contains a tightly rendered sketch, a long map illustrating how the fence would wind across the land and into the ocean, and color (and maybe fabric) swatches of the proposed fence materials.

A little expertise from Caitlin Brague:

Christo and his partner Jeanne-Claude document and conceive of, and fundraise and install the project themselves… one way to acquire the funding is to get environmental impact reports and all the materials and all the crew that needed for something like this, they’ll make [drawings] and then sell them and they can use the profits from the drawings to fund their next project… So this is both a preparatory drawing and also a finished drawing. - Caitlin Brague, Museum Specialist, National Gallery of Art

Not only did these drawings pay for the project but they also helped capture the imagination of the hundreds of people. To make the project happen, the artists need members of environmental organizations, local government officials, ranchers and land-owners, workers, and the public. All had to be on board for this audacious idea to fly.

“For me, aesthetics is everything involved in the process — the workers, the politics, the negotiations, the construction difficulty, the dealings with hundreds of people (…). That’s what I’m interested in, discovering the process. I put myself in dialogue with other people”. - Christo

Even with their convincing drawings and their team’s legwork, Christo and Jeanne-Claude faced resistance. Some community members and local government officials still scoffed. One local man said “It’s all a bunch of garbage. I think it’s stupid… What kind of art is that, hanging a piece of rag up for 50 miles? I can hang a rag up!”

But the duo persisted, spending months (years!) in conversation with each of the stakeholders. They went door to door, got to know the locals, became part of the community, and eventually won people over.

Here’s how one local landowner cleverly expressed her support of the project during a local commission meeting:

I’m Mrs. George Nicholson from Petaluma. The fence does go through our property. We welcome it. There was one thing said about art being temporal. Some of the meals I prepare aren’t much… But sometimes I go to a lot of work to prepare a meal that I think is art. It’s a masterpiece. And what happens? It gets eaten up and disappears.

I just love that.

It was touch and go til the moment it was complete, but the team was strategic, stubborn, and tireless. They would not stop, even breaking a law at the last minute to make it all come together. On September 7 of 1972, Running Fence was completed.

Christo called the finished piece a “ribbon of light.”

A 1977 article in the New Yorker shared the public’s response:

“It’s just so goddam flipping outrageous,” a long-haired kid in torn jeans said happily. “I can’t wait to see the rest of it.”

How did these artists dream BIG? How did drawings help?

So how did Christo and Jeanne-Claude come up with such big, impossible, irrational, outrageous ideas?? And how did they go from a little sketch or drawing to a 24-mile-long multimillion dollar installation?? What can we learn from their approach to dreaming big?

Here are four tips I gleaned from learning about the duo’s work:

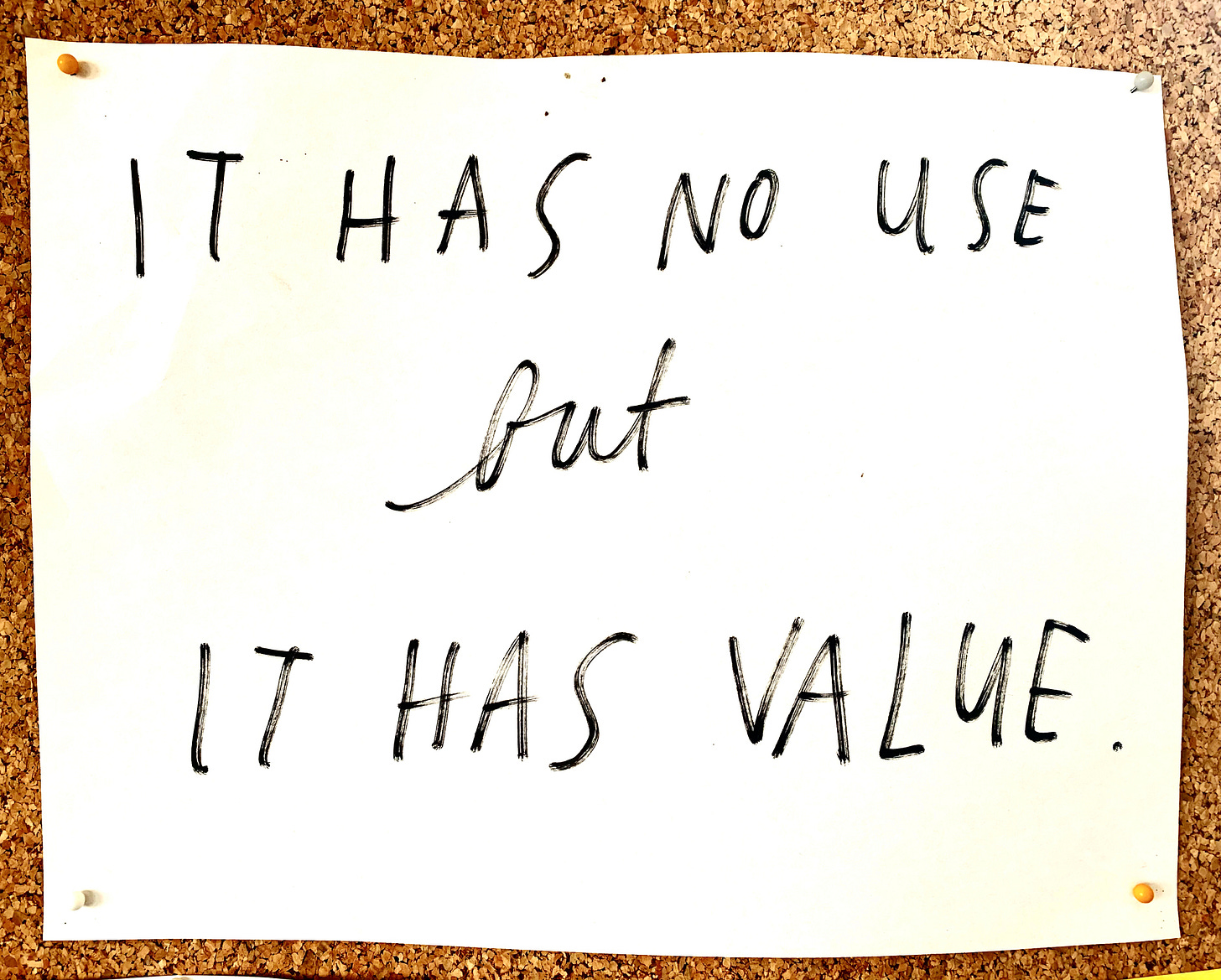

1. Forget usefulness

Start by letting go of the expectation that art has to be useful, or say something, or mean something. Christo believed that art was an experience — and that his art was ultimately useless. He said:

Basically you don’t think on that order when you start to do things. You know there’s not rational thinking. All these projects, I tell you, they are absolutely useless. Nobody needs the project except myself and JC, we convinced some friends to help us. And if someneoy likes them it’s also a bonus. The world can live without Running fence. Don’t care about that thing.… Art is something absolutely useless.

Why is that important? Because we live in a culture that prioritizes use value over all other values: aesthetic, spiritual, relational. In a culture where productivity is king, everything we do must be for a concrete, quantifiable purpose.. When we move past that narrow perspective and embrace the experience for its own sake, a whole new world cracks open.

2. Don’t be practical

“These projects are totally irresponsible, capricious, unnecessary!” - Christo

Another thing to let go of? Practicality! Experience with a certain medium? Nope! Contacts in a certain place? Not necessary! Jeanne-Claude and Christo didn’t necessarily know how to make the things they imagined. They saw each project as an opportunity to learn.

“The project it was something unforgettable because we — myself and Jeanne- Claude — we learn so much things we did not know. Each project for us is like university, we’re so eager.” - Christo

3. Want to think BIG? Start SMALL.

When they had the first whiff of an idea, Christo and Jeanne-Claude would start sketching. From those small sketches a body of work would evolve: drawings to work out the object, the installation, the location.

The first drawing has very little drawing, done on brown paper with very little text underneath. — Christo

And then push them to grow big. Because after all, why not? It’s art!

They are only big because they are absolutely nothing except a work of art. And that gravity, that is words work of art looks big, they are humble works of art. — Christo

4. Beauty for its own sake

“We want to create works of art of joy and beauty, which we will build because we believe it will be beautiful”. - Jeanne Claude

“Artists do not retire, they simply die.” - Jeanne-Claude

Other artists with big ideas

Most monumental works of art are made by men, and white men in particular. Taking up a lot of space and breaking rules to do it is something that white men have done all over the world for a very long time. So it feels important to talk about other inspiring examples of art on an audacious scale.

Kara Walker

A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, the first public installation by artist Kara Walker. It was located inside the Domino Sugar Plant in Brooklyn, New York. Its full title is A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant.

It’s built out of styrofoam and and 40 tons of sugar. Anne Pasternak, President and Artistic Director of New York–based nonprofit arts organization Creative Time, says in this phenomenal short film about the project, “The project is not just ambitious in scale, it’s ambitious in content. Kara Walker is encouraging us to look at things that are so visible in our society that we wish were invisible. Our history to slavery and our contemporary relationship to slavery, immigration, migration, mythologizing of Black women’s bodies… We believe at Creative Time that public art creates a space to engage in those difficult conversations.”

Simone Leigh

Another monumental project: Simone Leigh’s Brick House, installed on the High Line in New York. You can watch a short film about the installation of the work here.

Simone Leigh’s Brick House is a 16-foot-tall bronze bust of a Black woman with a torso that combines the forms of a skirt and a clay house.

In a New York Times profile of Leigh and the work (gift article link here so you can read!), Leigh was asked why she created the giant sculpture for that particular public place. She said she thought “it would be a great opportunity to have something about black beauty right in the middle of that environment.”

Also from the NYT Piece, Cecilia Alemani, director and chief curator of High Line Art, said, “It’s an icon, it’s a goddess — this very powerful feminine presence in a very masculine environment, because all around you, you have these towering skyscrapers and cranes….It’s very rare that in the public sphere you see a black person commemorated as a hero or simply elevated on a pedestal.”

Reflection

How are Kara Walker and Simone Leigh’s monumental public artwork similar or different from Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s approach to public art, if at all?

When we are confronted with a spectacular artwork at substantial scale, we could ask ourselves: Why was it made that size? What does it say about the artist, and their intent? And what does our response say about the culture?

And if WE were going to dream BIG, what would we do?

What would YOU create?