Beyond Protest Posters: How Artists Engage with the World

Part two in DrawTogether's series on Creative Action.

Hellllo, friends.

Welcome to Part Two of our Three-Part Series on Creative Action! As a reminder, I’m taking the paywall down for this entire series, including videos. If you can subscribe — annually, especially — that’s how we can do things like this. And if you DO NOT want DrawTogether to offer more free, engaged creative practice projects for folks like yourself and others around the world, DO NOT SUBSCRIBE.

Thank you.

All right, Part One of Creative Action was all about the Why. Why it’s important for artists to make art in tumultuous times. Why it’s good for us, good for others, and good for the world. Beth Pickens shared her experience counseling artists, writing books and starting a publishing house herself. Read part one here, and watch my conversation with Beth here.

In Part Two, we look at the How.

Today, we’re taking a tour of artwork by artists who engage in Creative Action in very different ways. When people think of engaged art, here’s what people often think: political posters and fliers. And that’s great. But it’s just one kind of political art.

In our dispatch today, we look beyond the protest poster and look at other ways individuals use art to engage with politics, and humanity. Some of their art is deeply personal. Some is universal. Some is local. Some is global. The art we’re sharing is less about telling people what is right and wrong, and more about asking provocative questions. It appeals to our humanity, and asks us to do our own thinking. Some might even motivate us to action.

Beth Pickens reminded us last week that whatever our medium and approach, we must make art right now, and we cannot censor ourselves. When the censorship of Amy Sherald’s painting Trans Forming Liberty prompted her withdrawal from the National Portrait Gallery, it showed up the next week on the cover of The New Yorker. Sherald said, “When liberty is conditional, art has to insist. Visibility isn’t granted — it’s claimed.”

This week let’s look at some work by artists who claim visibility, and insist on liberty.

ART THAT INSISTS

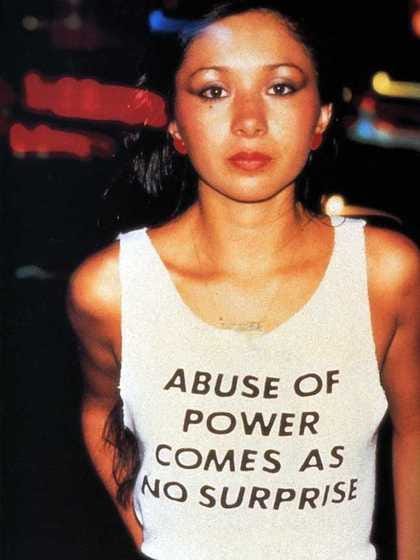

Jenny Holzer, Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise

Artist Jenny Holzer blurs the line of art and activism, using text to provoke viewer’s thoughts about society, power, consumerism, justice, and humanity. In her series Truisms (1977-1979), Holzer wrote 300 pithy, challenging, even cliche phrases — and placed them in public spaces: everywhere from phone booths to electronic billboards in Times Square. Holzer considers text itself an image — the text is the art. “Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise” (above) was the piece Beth referred to in our conversation. Another favorite Truism of mine: “Protect me from what I want.”

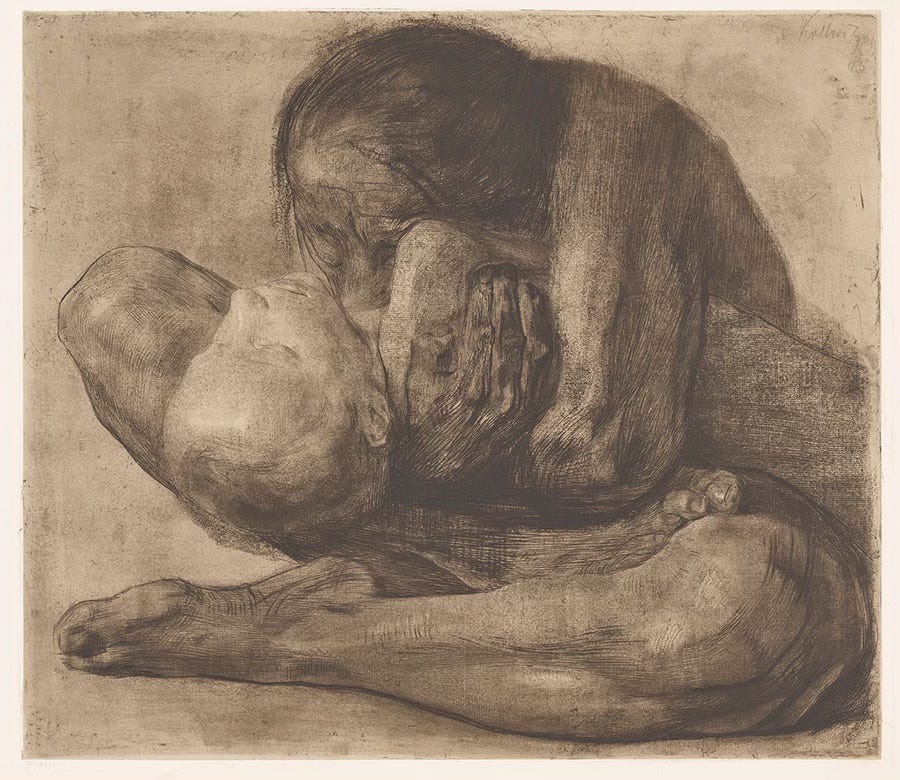

Käthe Kollwitz, Woman with Dead Child

At a time when women artists were encouraged to create images of happy babies and vases of flowers, Käthe Kollwitz looked closely at what was happening around her, and used drawing to expose the atrocities of war, poverty, and social injustice. Raised by politically-engaged parents, Kollwitz focused her art on the personal experiences of the working class and the suffering caused by conflict and oppression. While the Nazis condemned her art as “degenerate”, they also appropriated her drawings for their own propaganda posters, and used a fake name to attribute them to another person. Her work was that powerful.

Judy Chicago, Dinner Party

Dinner Party is an incredible (and massive) piece of feminist art by Judy Chicago. This installation features a triangular banquet table set for 39 women of history and myth to gather together, swap stories, and challenge the patriarchy. Each woman has a table setting customized to reflect her life and work. On the floor tiles, you can see the names of 999 more women, and their placement symbolizes how many women’s achievements were silenced or undervalued. You could spend hours viewing this piece and taking in the details, as well as debating who should have been included at the table (or how Chicago might have made different choices today, almost half a century later).

Leilah Babirye

Born in Uganda, Leilah Babirye creates artwork that celebrates queer identities. She confronts the harsh oppression of LGBTQIA+ people in Western and Central Africa by reclaiming the regions’ artistic traditions for her own queer community.

When Ugandan educator and LGBTQ-activist David Kato was assassinated in his home. Being Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Queer and/or Trans is illegal in Uganda, and as the LGBTQIA+ community publicly mourned and protested his murder, they wore masks to hide their identities. Babirye decided masks would be the focal point of her work, as a way of exploring and representing the lived experiences of queer people in a homophobic society. She said, “That’s when I started making real art.”

For more, you can read our feature on Babirye from a few months ago!

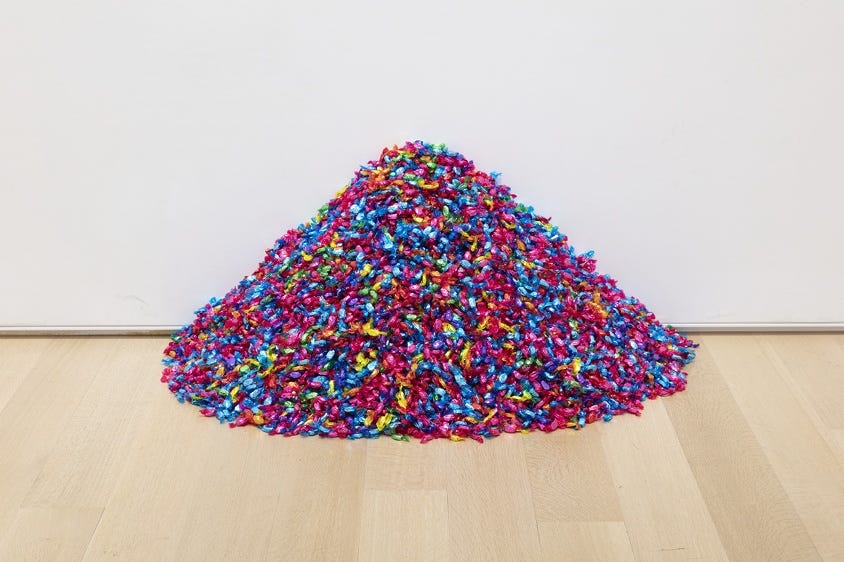

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s best-known works invite the viewer to interact with them. Born in Cuba and openly gay, he explored identity within his art, and he challenged standard forms, such as the portrait. Debbie Millman shared this piece with us in an earlier dispatch about visual storytelling: “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) is an installation consisting of approximately 175 pounds of individually wrapped candy. The work’s form and scale are always changing, impacted by the piece’s placement in the gallery and the audience’s interactions (visitors can take the candies if they like). ‘175 pounds’ refers to the ideal weight of Gonzalez-Torres’ partner Ross Laycock, who died of AIDS in 1991. Gonzalez-Torres died of AIDS in 1996. As visitors take candy, the configuration changes, linking the participatory action with loss—even though the work holds the potential for endless replenishment.”

There have been controversies over galleries and museums displaying Gonzalez-Torres’s work without mentioning his queer identity and AIDS. These omissions are a shameful erasure of his own declarations of self and community in his work.

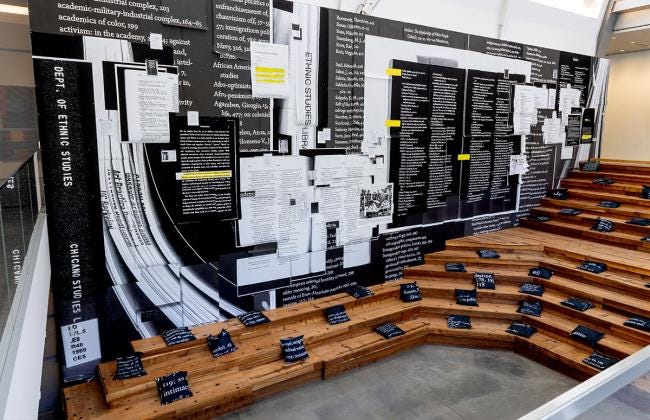

Stephanie Syjuco, Present Tense (Roll Call)

Artist and professor Stephanie Syjuco describes this installation as "an oversized love letter to teaching and learning during fraught times, and the constellations of knowledge we carry forward with us." Currently on view at the Berkeley Art Museum, the layers of paper come from Syjuco’s exploration of UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library and Ethnic Studies Library and from educators around the nation who shared key texts from their own teaching practice. Berkeley’s campus played a key role in the birth of ethnic studies programs in the late 1960s, and her piece “responds to the broad backlash against and recent legislative attacks on ethnic studies, book bans, and the defunding and removal of diversity programs.” Enlarged indexes with fragments that don’t neatly line up speak to the roll call in the title, and curator Matthew Villar Miranda notes that many of the terms overlap with those censored by the federal government in a list compiled by PEN America.

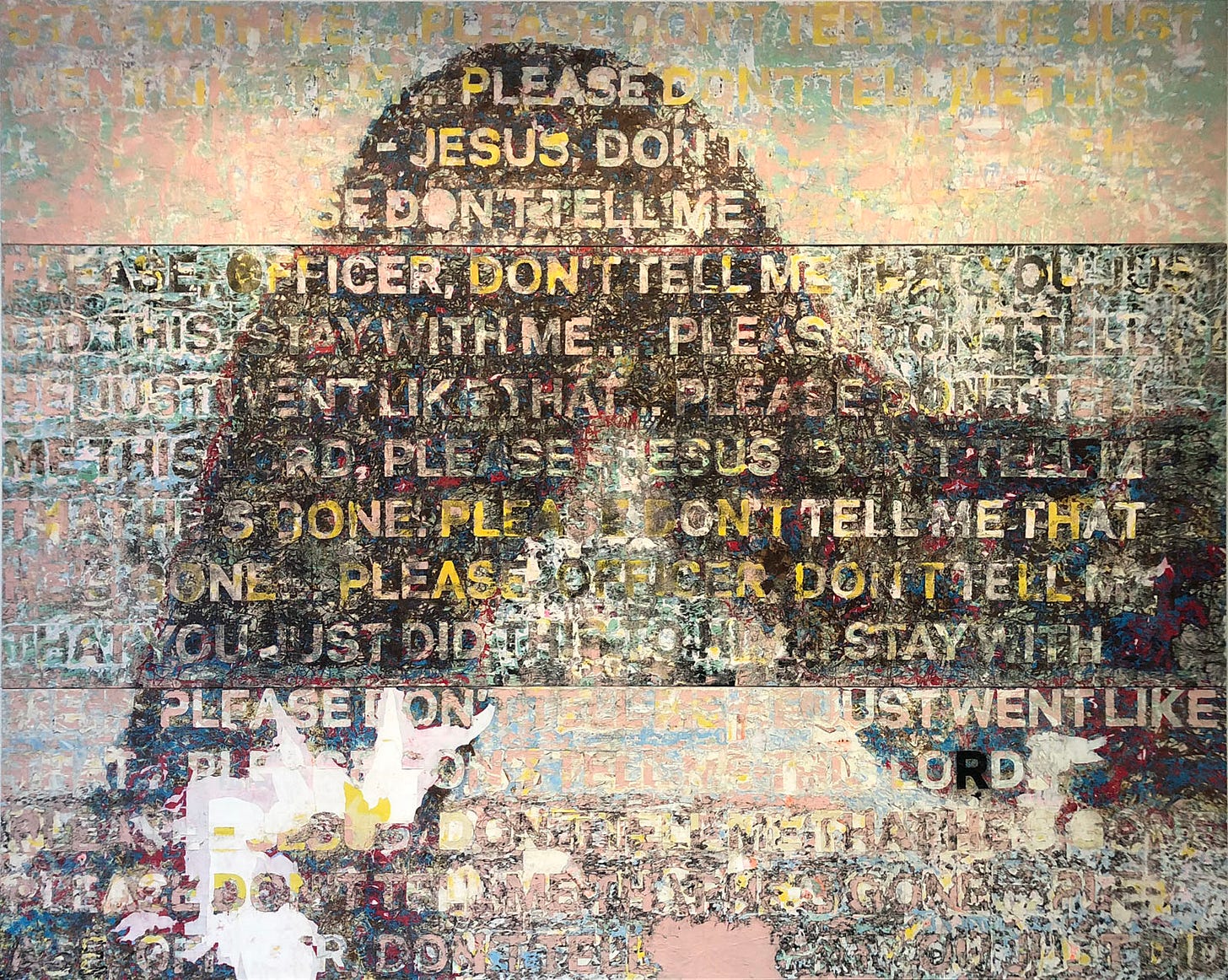

Mark Bradford, 150 Portrait Tone

This painting is enormous, and towers over you when you walk into the building foyer at LACMA. If you are familiar with Mark Bradford’s work, it is obviously his. As I struggled to make out the words, I gasped because I realized where they were from: Diamond Reynolds’s streaming of the killing of her boyfriend, Philando Castile, by police. My familiarity with Bradford comes more from how he engages with history, and this painting makes me think of the sense of urgency he must have felt, the need to memorialize this moment, to make it big and demand attention rather than let it get cast aside. He painted this within a year of that horrific event. The title is a commentary on a paint code that assumes people’s skin is a certain shade of pink.

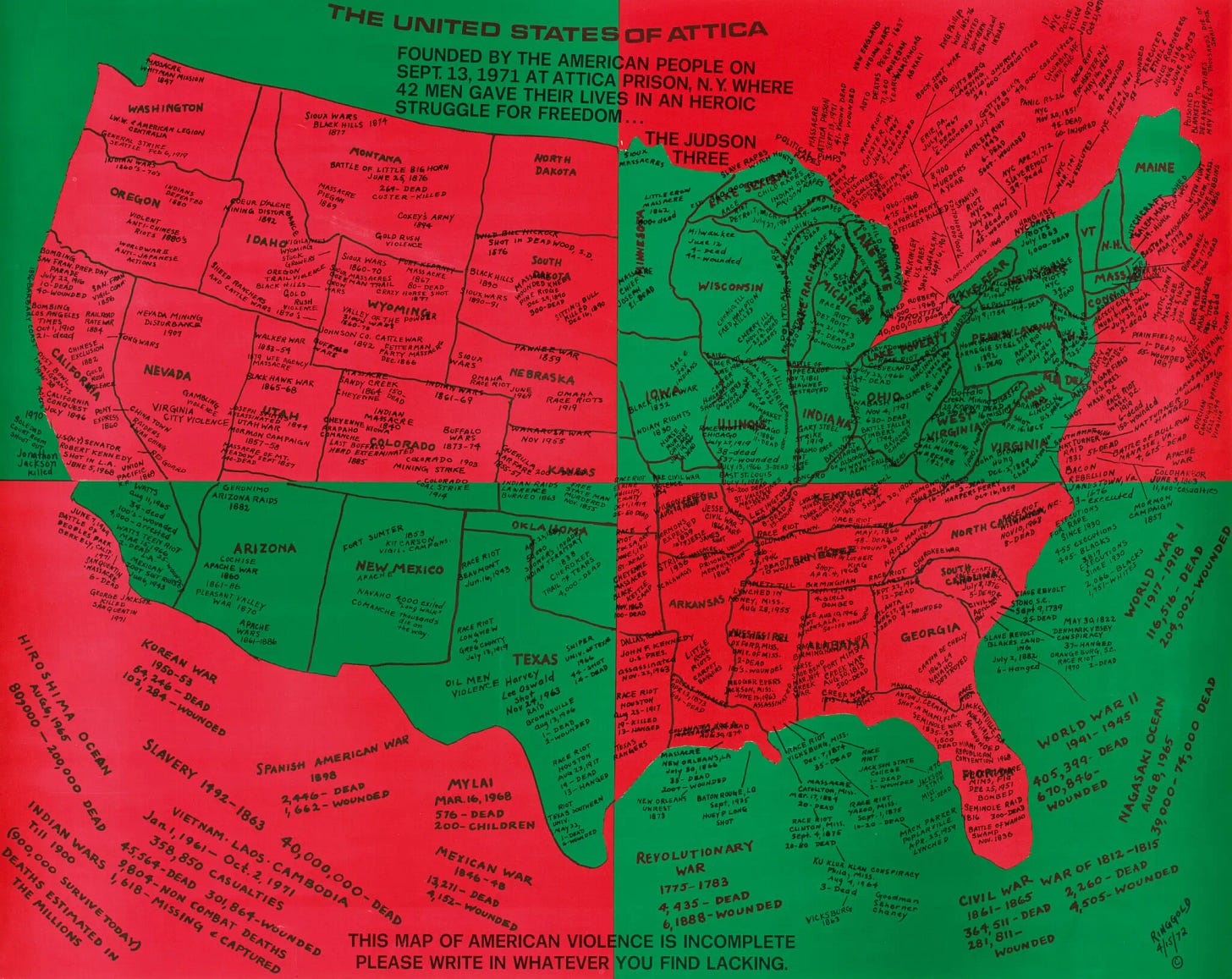

Faith Ringgold, The United States of Attica

In 1971, prisoners in the Attica maximum security prison were fed up with the terrible conditions there and revolted, taking over the prison in an uprising that killed one officer. Negotiations over prisoners’ demands ensued but ended with a violent assault by law enforcement who killed 29 prisoners as well as 10 prison guards and employees. Faith Ringgold, a Black multimedia artist most known for her colorful, narrative quilts, responded with this piece that same year, placing the event in the context of a “map of American violence” including the genocide of Indigenous peoples, enslavement and lynchings of Black Americans, and American imperialism. The colors come from the Pan-African flag and speak to a sense of unity and solidarity across people who experienced violence and oppression from the American government. She also invites the viewer to contribute and “write in whatever you find lacking.”

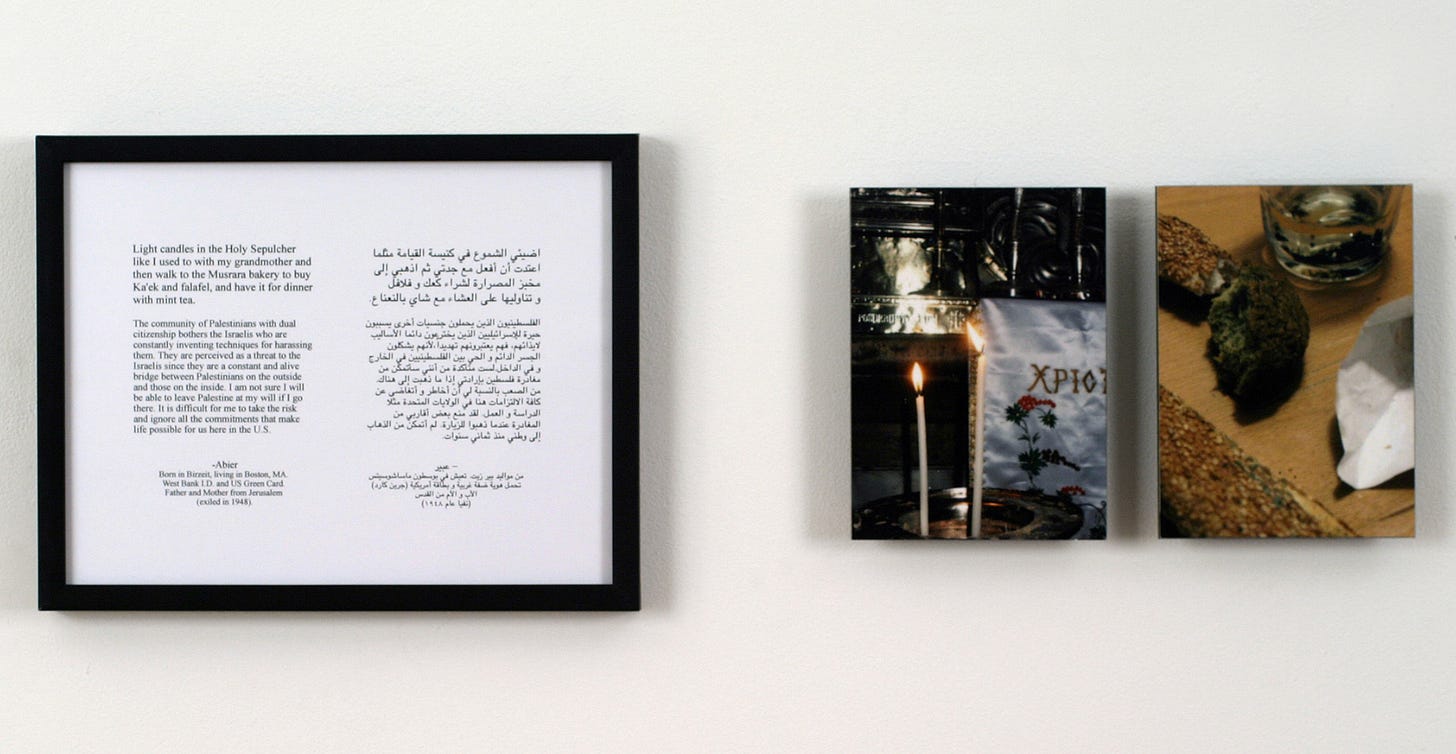

Emily Jacir, Where We Come From

In her artwork Where We Come From (2001–03), Palestinian Artist Emily Jacir posed a question to Palestinians living in the occupied territories and abroad: “If I could do anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it be?” Jacir did as they requested — going to visit a specific location, eat a special food, or visit a beloved relative. She documented the tasks and actions in a series of photographs, texts, and videos, and presented them in museums, offering viewers insight into the effect of the Israeli occupation on the lives of her and her community. This takes on an extra layer of meaning, as we are currently uncertain if the people in these photos are still alive, and if the places still exist.

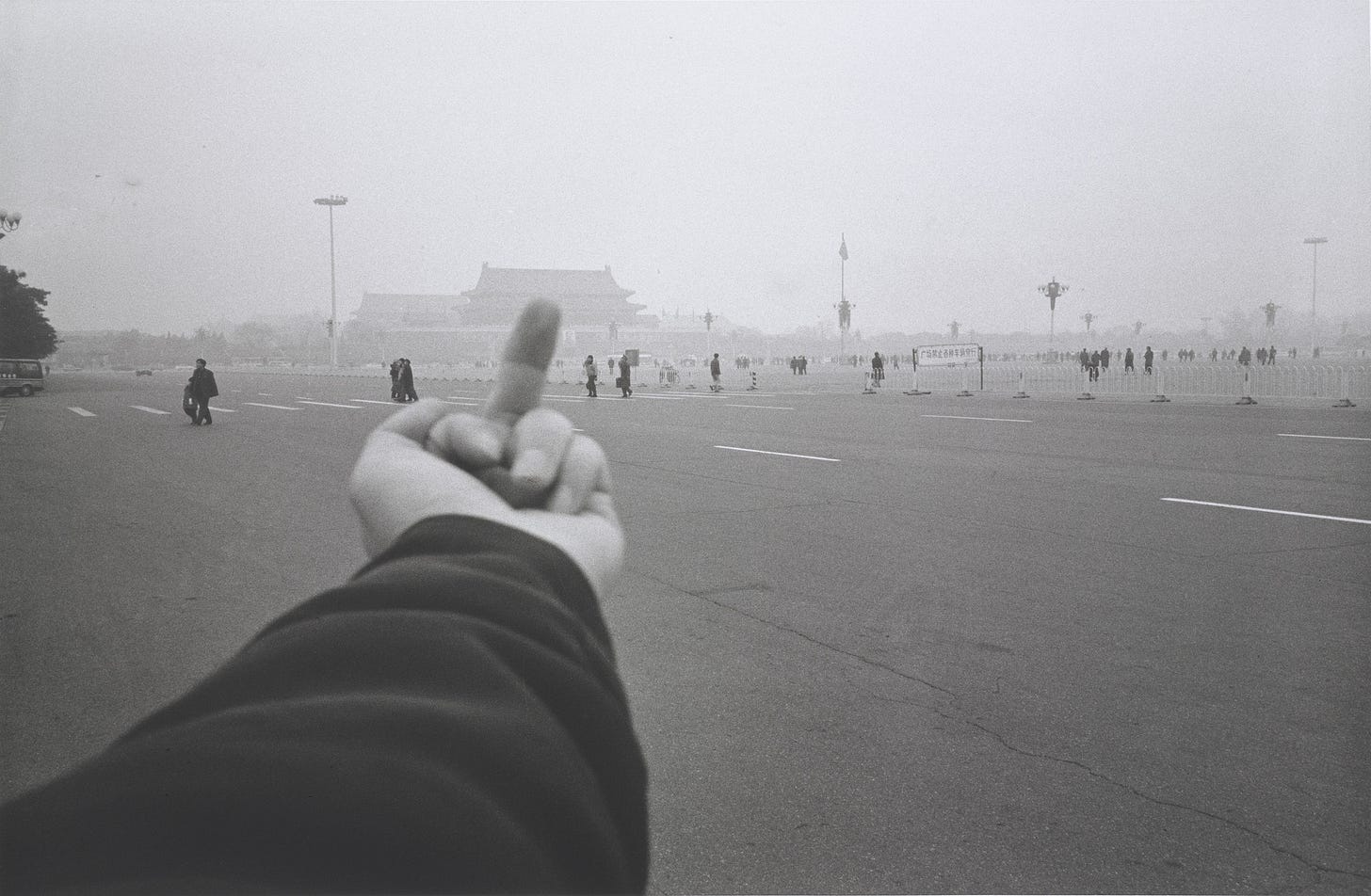

Ai Weiwei, Study of Perspective

Ai Weiwei’s photographic series Study of Perspective (1995 — 2003) depicts him giving the middle finger to iconic landmarks around the world. The gesture, widely understood to mean, well, “fuck you”, represents a response to tyranny, political oppression and injustice, and a defense of freedom of expression — a freedom restricted in his home of China.

Jeffrey Gibson, The Space in Which to Place Me

Jeffrey Gibson draws upon his Indigenous heritage, Queer identity, American and global history, as well as pop culture, to create vibrant paintings, sculptures, and videos. Even as he addresses painful histories of oppression, there is a pride and joy that emanates from his colorful work — an insistence on recognizing the resourcefulness and resilience of Indigenous and other marginalized peoples. In 2024, Gibson was the first Indigenous artist to represent the United States with a solo show at the Venice Biennale, and those works are now on view at the Broad in Los Angeles. In this room, ancestral figures with beaded text referring to Reconstruction and legislation affecting the civil rights of Black and Indigenous Americans flank a quotation from Martin Luther King, Jr., advocating for us to see ourselves in relation to history and our own agency.

Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death

Influenced by Pop Art and New York graffiti, Keith Haring developed a style all his own. From making his own graffiti in the subways to creating large murals, he thought a lot about how his art would interact with the public. Haring was a prolific artist, and as the AIDS crisis claimed the lives of more and more friends and community members, he felt called to make and do even more. Diagnosed with AIDS himself in 1987, he used his art to build awareness about HIV/AIDS and contributed to funding actions by ACT UP until his death in 1990.

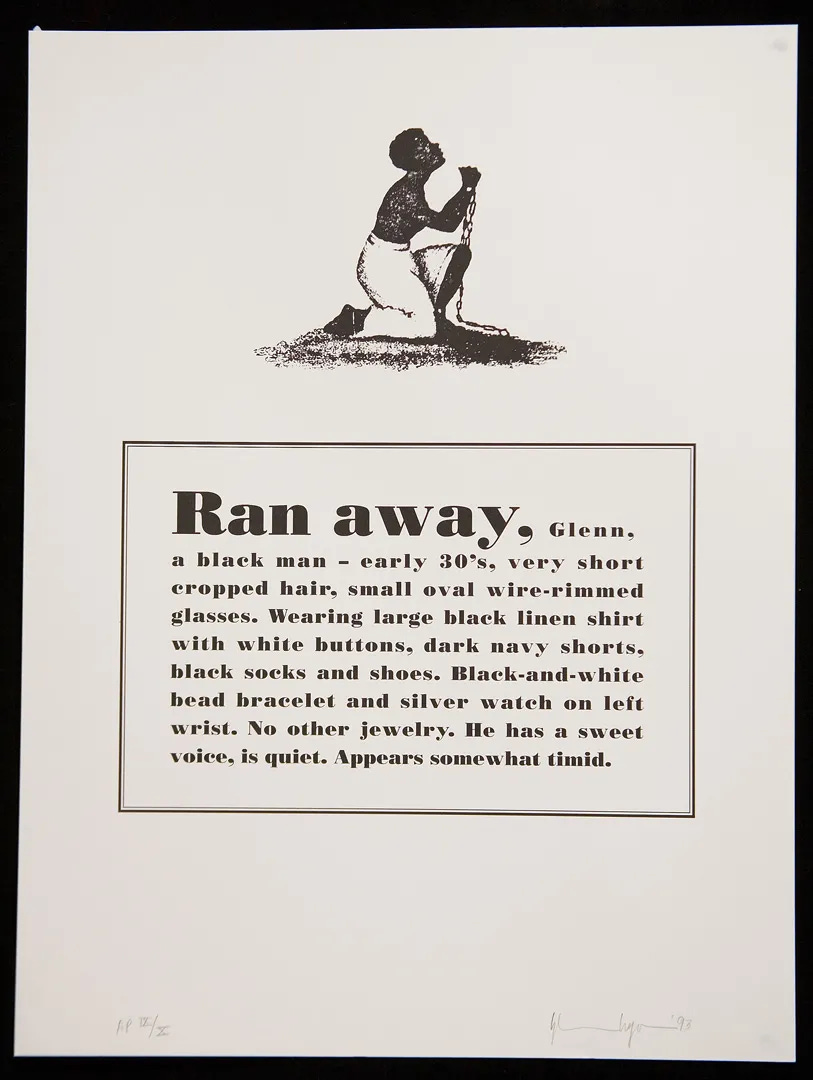

Glenn Ligon, Runaways

Asking his friends to describe him and then merging that with ads for runaway slaves? To me, it gets at the precarity of being a Black man in America — how little distance there is between your friends’ descriptions of you in the 1990s (by people who care about you!) and descriptions by enslavers who viewed them as property. I think it’s one of the most brilliant works to engage with history and race that I’ve ever seen. This feels especially relevant as Trump announced this past week that he feels the Smithsonian focuses too heavily on the US history of slavery, and should focus more on “brightness.”

Ronald Rael, The Teeter Totter Wall

Ronald Rael, a professor of architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, and Virginia San Fratello, an associate professor of design at San José State University, came up with the idea to span the US-Mexico borders with see-saws as a response to the Secure Fence Act in 2006, which started large-scale building on the border. From an interview in the Guardian: “Walls don’t stop people from entering our Capitol,” Rael added. “Walls don’t stop viruses from moving. We have to think about how we can be connected and be together without hurting each other.”

The Assignment: Engage

Let’s do a little digging of our own! Is there an artist above whose work strikes you? Or someone you know of whose work you don’t see above that you would love to share with our DrawTogether community? What kind of engaged artwork speaks to you?

This week our assignment is to do a little research on your own and find a piece of art that speaks to you. That makes you ask questions. Feel something. Look at your world in a new way. Then do a little reading about the artist. What is their story? How did that artwork come to be? Jot down a few notes.

Then share that artwork and a little backstory on it ,and why it appeals to you, in the community chat. Let’s curate our own gallery of Creative Action , and learn from one another.

While we’re making our Creative Action lessons and assignments free for everyone, we are keeping the community chat closed to paying members to make sure the community is a safe space for all. Want to join in the conversation? Become a member:

Instructions:

Step 1: Choose an artwork or artist who has inspired you with their engagement. If you are looking for more inspiration, here’s a list curated by several artists for the New York Times.

Step 2: Engage with that work/artist more deeply. Learn about them, learn about their cause or struggle. We are asking you to do a little more legwork than usual this time.

Step 3: Draw about it. Engage in a visual exploration of the piece. That might involve sketching it or part of it, but it could also be a quote. Make it personal.

Step 4: Share in the chat. We will learn from each other!

Alright, everyone, I cannot wait to see what you share.

We’ll be checking in on Wednesday with some inspiration to keep us going on our three part dive into art as Creative Action. Stay tuned.

Pencils up! ❤️✏️❤️

xoxo,

w

Kara Walker’s silhouette cut outs of antebellum slavery are powerful reminders of racial inequities that persist today. Her monumental sphinx like sculpture from 2014 titled “Sugar Baby” of a supine black woman wearing only a headscarf and made entirely from white, granulated sugar projects defiance in her subjugation. There are many levels of oppression defined in this work, which was designed to eventually crumble to dust.

I am LOVING and appreciating your focus. THANK YOU for showing up here to help. XO!