Art Sports!?

We draw with our bodies, so let's give our bodies some attention.

Hello, my fine DrawTogether Grown-Ups Table friends. So happy you’re here.

I got so many nice notes from folks about last week’s exploration into Frida Kahlo’s home Casa Azul, and the question of what makes a creatively inspiring space. I am considering moving from my little home in Oakland to live/work/create somewhere with more space and light, so seeing your drawings about your creative spaces is truly inspiring to me right now. A curated selection of GUT members fabulous artwork is at the bottom of this dispatch. Love the great, supportive energy in the GUT chat. Let’s keep it going.

The Physicality of Drawing

I’ve been thinking a lot about bodies lately. How our physical experience of the world is so fundamental to who we are and our experience of the world and others, yet it is so often de-prioritized and pathologized. So many of us were trained to ignore and override the essential information our bodies offer. Often we can barely hear it. And in the case of drawing, something that we start doing at a young age with our BODIES (think of the dynamic physicality of a child finger painting! of bashing clay into a shape with our fists), we stop thinking of it as something with do with our whole bodies, and just related it to our brain, our eyes, and our fingers.

A little personal and challenging story for you that I’ve never shared before. (Bear with me. It is about drawing, I swear.)

When I was fourteen my parents were struggling to handle their precocious, creative, rebellious, big feelings child. Desperate, they took the advice of an educational advisor, got some financial support from a wealthy family member, and sent me to a boarding school in New England. Why any “professional” would suggest this California kid attend a conservative boarding school on the other side of the country is beyond me… let alone one where gendered clothing (skirts!) were required, and we had to go to church twice a week (I am a jewish atheist!) But… that’s where I went.

The biggest issue for me wasn’t the church or the skirts. It was the sports. This school was very sports-focused. Classes (which were held six days a week) ended every day around 1:30 so THREE HOURS could be dedicated to sports.

Friends, I was not into sports. Never have been. And what’s more, I was a fat kid. I say that without judgment. It’s simply a fact. More important, I was severely out of shape. I couldn’t run a lap around the track without feeling like my lungs were going to collapse.1 I was always last being chosen for teams. (If schools have not stopped this practice, my god, please stop!) I could not and did not want to participate. I was different than the other kids. I didn't fit in.

I was an Artist. I had drawn my whole life. Drawing made me feel good about myself. I got a lot of praise for my interest, commitment, and skill. I’d been drawing nude models since I was 12, dammit! I while I felt different from every kid at this sporty boarding school, in my mind, the only thing that made me okay was being an ARTIST. I clutched that identity so tightly to my chest. It cushioned the blows I received from kids (and more, myself) every day.

The New Englanders did the best they could with this expressive, emo girl and agreed to give me an “art exemption” from sports. That meant while all the other kids were active and went to play sports together six days a week, I returned, alone, to my cinderblock dorm room where I drew and painted on a mini-easel and I ate. I ate A LOT. I was sedentary. I gained more weight. I felt more and more disconnected from my body, and further and further apart from the other kids at school. I rejected the idea of anything body-focused as being worthwhile. But art was worthwhile. It was safe. It had nothing to do with my body, or the rejection I experienced around it.

After one year, I returned home.

Look, everything ended up okay. It certainly could’ve been worse. And ultimately I’m grateful for the experience. But the challenging residue of something like this - for me or anyone - is long lasting. I still struggle with the strict, false dichotomy I set up of my life as a solo artist OR being in relationship with people. And the downright untrue belief that moving my body and making my art are at odds with one another. That there’s art. And there’s sport. And never the twain shall meet.

Silly artist. Art can be sports, too.

Over the years, dancing, yoga, weightlifting, and most recently, a peloton, have helped me become more comfortable in my body. But I am still working to becoming more “embodied” in my art. To be aware of my body while I’m making art. To see my physical self and my artistic self as one and the same.

Which brings us back to the topic at hand: drawing with our bodies.

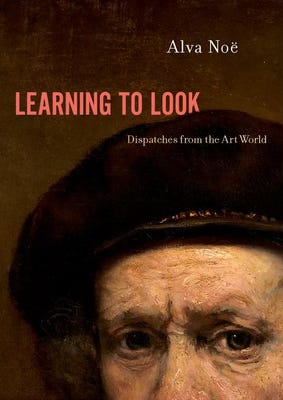

Here’s a short, sweet essay on drawing with our bodies by philosopher Alva Noë.

Speak, Draw, Dance

by Alva Noë

As snail moves down the garden path and leaves a trail of ooze behind it. It leaves its mark. So begins the natural history of drawing.

To draw is to make marks, and marks are - certainly before the age of printing and the computer - always the traces of movement, or action. Writing, we forget, is a special of drawing, not a species of talking. In our culture we tend - usually unwittingly - to think of talking on the model of writing: we take ourselves to be stringing together sounds to form a linear progression of words. We forget that talking is a strange ballet we undertake with the tongue, lips, throat, eyes, and hands. Talking is like dancing, and writing — well, writing is a way of making traces; it is a kind of drawing. (In Old English, writan meant “to score, outline, draw the figure of.”)

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s performance of an excerpt from her work Fase at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2011 as part of the exhibition “On Line: Drawing Through the 20th Century” Combined all these ideas and much more. Seen from above, and as captured in photographs by Thierry de Bey, the dancer’s movements disturb the sand floor. As she steps, she draws, she writes, she dances, and she sings.

Alva Noë2 is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of California Berkeley whose work focuses on the nature of mind and human experience. The above essayette3 is from his collection Learning to Look: Dispatches from the Art World.

So what does all this have to do with HOW we draw. How can we integrate our bodies into our art making, and vice versa?

Drawing with Our Whole Bodies

We usually think of drawing as something we do with our eyes, our hands and our minds. And it’s true, we do rely on our fingers (or some kind of fine-motor tool.) But when we draw we also employ our shoulders, our back, our neck, our jaw. Our breath. Pencils, crayons, pens, brushes and chalk are just extensions of our movements. Or our stillness. The primary tool of drawing is our body.

When you draw something small and tight - say, hundreds of scales on a long, small snake, or maybe a thousand tiny circles - how do you hold your body? Are you sitting or standing? How close are you to the drawing surface? What is the shape of your back? What is the expression on your face? If you’re anything like me, you’re hunched, tense and tight, from tip of your head to your toes. Unless you are deliberately deepening your breath (like we do with this exercise and this exercise) your breathing may be short and shallow. Think about it: your body = your drawing: it’s pulling inwards. Your small, tight shape follows the shape of the drawing. (Or does the shape of the drawing follow you?)

Drawing can also take us seemingly out of bodies and into our minds as we process thoughts and memories. It can help our imagination flow. We may feel like it’s a separate thing that’s happening, but it’s precisely through the physical act of drawing that we can achieve this experience.

Drawing is a physical, embodied experience that leads to a physical, embodied outcome.

Have you ever tried figure drawing, with a live model?4 When I draw a model I catch myself shifting my weight to mimic their pose. That way I can better understand what the subject feels like - what muscles they’re using, where the weight is being held, how it maybe impact their emotions. And that informs my drawing.

Drawing a portrait, I catch myself mimicking their expression. I furrow my brow to match their grimace, tighten lips and turn the edges down, clench my jaw. And my pen responds in kind. How can we draw an expression of feelings if we don’t understand what if feels like to make that expression ourselves? Which muscles are tight, which are slack, how a tilt of the heads effects a mood.

When we draw, we draw with our whole bodies.

While most of us can’t jump up and rush off to a figure drawing class, there are a few things we can do experiment and play with the physicality of drawing right now. Some experiments we can do to become aware of how our bodies and our drawing are one.

Assignments: Experiments in Embodied Drawing

Instead of one big assignment, I’m giving you a bunch of little experiments to try. You can try one or all of them, and share the along with how they did (or did not!) impact your experience drawing with the GUT community in the chat. I’m so curious to hear what these experiments do for you. They are based on my experience of drawing over time, and I’ll be revisiting them in the week ahead, too.

As far as subject matter goes for these drawings, it can be anything you like. I bought myself some flowers at the market yesterday, and I’ll be drawing those.

Okay, ready? Let’s do this.

1. Draw Standing Up.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to DrawTogether with WendyMac to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.